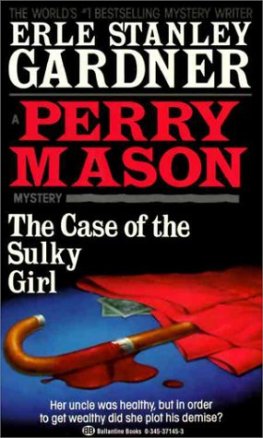

J OHN F. K ENNEDY , P RESIDENT OF THE

U NITED S TATES OF A MERICA 19611963

It was after tea on a school night when I found the dead body. Id gone out to the shed to fill up the coal bucket, which was as good an excuse as any to escape our kitchen for a moments peace. Being a Tuesday, wed had just pie and mash for tea, and being a day with a y in it, my big sister Bev was arguing about why it wasnt her turn to do the dishes. Our terrier Flea, an excellent listener, was waiting patiently for any leftover pie. And all Mum did was turn the radio up louder. It was that new Beatles song again, the one that went Love, love me do, which, with the clatter of plates and smell of mashed potato, was giving me a headache.

Outside, the evening was inky black. The air had a bite of frost to it, and the only sounds were the distant hum of cars, and next doors water gurgling down the drain. I stood for a moment, enjoying how peaceful it was to not hear Bev yakking on, or the radio playing hit song after hit song because Mum, who hated silence, had barely switched it off since Dad died.

I went down the two steps to the shed and opened the door, only now switching on my torch. I was checking for spiders, mostly, and certainly wasnt expecting anything else to appear in the torchlight. But it did. Something woolly and green. A bobble hat.

I took a tiny step closer. My heart began to thunder.

The hat was on a persons head.

They were lying against the coal heap, facing the far wall. All I could see was the jut of a cheekbone. A coat collar turned up against the cold. A muddy hand that looked more like a freshly dug potato than anything human. The person wasnt moving: they were either very fast asleep

Or dead.

I backed out of the shed faster than any spider could make me move. With the door shut and bolted, I caught my breath. I tried to think. The sensible thing would be to go straight back inside and tell Mum, whod rush round to our next-door neighbours and ask to use their telephone to call the police.

But Id never seen a dead body. And I was curious for a look just quickly, just to be sure though I was far too scared to go back in the shed by myself. So I did the unsensible thing: I went across the street to my best friend Rays. Hed never seen a dead body, either, and I knew hed be up for it, given half a chance.

*

It took Ray ages to come to the door. Id started shivering by now the shock, I supposed, and excitement and the cold, because Id come out without a coat. My finger hovered over the doorbell. Obviously Ray was in, because the television was on and I could hear his sisters annoying laugh through the glass. I was about to press the bell again, when he opened the door.

At last! I cried.

Whats up? Ray looked a bit put out, as if I was interrupting something.

You need to come over to mine, I told him. Like, now!

I couldnt say any more when his family were in earshot, but hoped he was getting the message. We lived on Worlds End Close, which was, without doubt, the dullest place on earth: a cul-de-sac of fourteen pairs of identical square white houses with net curtains at the windows and box-hedged gardens at their fronts. The garden at number two didnt quite count because no one had cut the grass there since old Mrs Patterson moved out in June. But the point was nothing ever happened round here. So, seeing a dead body might well be the single most exciting and terrifying moment of mine and Rays lives.

Ray glanced down. Whats with the coal bucket?

What? Oh! I hadnt realised I was still carrying it. Never mind that. Can you

Ray? His mum interrupted from the sitting room. If thats Stevie, bring her inside.

Unlike my family, Rays used their sitting room every day: from it came the sound of dramatic, thumping music. They were lucky enough to have a television, and I often popped over to watch crime dramas and game shows, and a bit of Blue Peter.

Its starting, Ray! Mrs Johnson called again.

Rays eyes flickered towards the sitting room: Id lost his attention now, I could tell.

President Kennedys about to be on, he said, beckoning me inside.

I hesitated. We had a dead body to inspect. Couldnt the news wait?

But Ray insisted. Itll only be a few minutes.

Defeated, I put down the bucket. A few minutes at Rays wouldnt make much difference. The body would still be dead. Yes, my mum would be wondering where the coal was, but the truth was Id never win over President Kennedy, not in Rays eyes: I knew better than to even try. Rays mum was British, and his dad was African American, which meant Ray and his siblings had cousins on the other side of the Atlantic. When people looked at his skin colour and asked nosily if he spoke English, hed say he was half-American, and proud of it. So proud he kept a scrapbook of cuttings from magazines and newspapers, and had written Important Americans on the front.

After the cold of outside, Rays sitting room felt deliciously warm. The curtains were drawn and the electric fire was on, the plastic logs glowing orange. All the Johnson family were there Rays parents, his sister Rachel and elder brother Pete, who did his hair in a rockers quiff.

Dont ever call me Elvis, Pete warned anyone who tried. Ray Charles, Chuck Berry, Little Richard theyre the true kings of rock n roll.

As well as a television set, the Johnsons had a modern swirly brown carpet and a posh brown velvet settee that you werent allowed to sit on if you were eating. Tonight, Rays mum and sister had pulled it closer to the television.

Hi, I said to them all, ducking behind my fringe. Though Id known Ray forever, I was still a bit shy around the Johnsons. It took me ages to get used to other people, and in a roomful of them, I tended to shrink into myself.

Pete lifted his chin at me in greeting. Rachel gave a little wave. Mr Johnson, Rays dad, glanced up from the screen.

Hey, Stevie, howre you doing? Fleabag not with you? He loved dogs like I did, and said Flea was always welcome, even after the time she ate the bathroom soap, then sicked it up on the stairs.

No, I answered, then whispered to Ray as we squidged on to the settee, Promise well be quick?

Itll be minutes, he assured me.

I folded my arms in my lap: I could probably sit still for that long.

On the TV, the intro music faded. The newsreader, with his immaculately parted hair and cut-glass accent, wished us all a good evening.