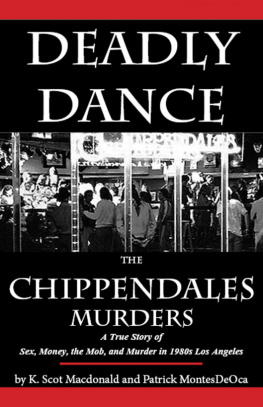

Deadly Dance

The Chippendales Murders

by

K. Scot Macdonald

and

Patrick MontesDeOca

Kerrera House Press

Copyright 2014 by K. Scot Macdonald

All rights reserved. No part of this publication maybe reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic,electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, tapingor by any information storage retrieval system, without thepermission in writing from the publisher.

Cover Image Enzo Giobbe

Macdonald, K. Scot and MontesDeOca, Patrick

Deadly Dance: the Chippendales

Murders/K. Scot Macdonald1st Edition

p. cm.

ISBN: 978-0-9916653-3-4

Smashwords Edition

Kerrera House Press

Culver City, CA

www.KerreraHousePress.com

First Printing: 2014

Printed in the United States of America

For photographs related to Deadly Dance visitKerreraHousePress.com.

This book would not have been possible without thecooperation of many people who discussed events they would haveliked to have forgotten, including Val and Tom De Noia, Marie DeNoia-Aronson, Michael Geddes, Bruce Nahin, Janet Hudson, SteveClymer, Jim Henderson, William Mott, David Drucker, and Ray Colon.Thank you.

Thanks also to Enzo Giobbe for permission to use thecover image.

Although every effort was made to discover whattruly happened, in such a complex story there are undoubtedly stillmistakes. Any such errors are mine and have been made with nomalice or intent to harm any living personor the memory of a lovedone.

On the last day of his life,Tuesday, April 7, 1987, 46-year-old Nicholas Nick John De Noiastopped by his office on the fifteenth floor of 264 West 40thStreet in Manhattan to pick up some business papers. Since 1981, DeNoia had been working for Steve Banerjee, founder and owner ofChippendales, first as choreographer and then producer of thecompanys male exotic stage show. Banerjee had gone to greatlengths to convince the reluctant New Jersey native to take the jobbecause De Noia was an excellent choice. His extensive credentialsincluded production of a play at Washingtons famous FordsTheater, five Emmys for excellence in television, including one fora series of childrens fairy tales for NBC called the Unicorn Tales , andexperience on Broadway.

By seeking to match the demanding artistic standardsof Broadway, the lean, muscular De Noia transformed theChippendales show from a bunch of muscle-bound jocks strutting andoften stumbling around on stage into a professional, Vegas-styleproduction with well-honed choreography, extravagant costumes andhigh-tech special effects that made the show an event of a lifetimefor every lust-filled woman who attended. Although a Chippendalesemcee described De Noia as equal parts Julius Caesar, P. T.Barnum, the Marquis de Sade, and Bob Fosse, the dancers loved himbecause the show became a phenomenal success and the Chippendalesdancers became international sex symbols.

By the mid-1980s at a time when theaverage American household was bringing in $770 a week, the NewYork Daily News reported that Chippendales tour profits had hit $80,000 aweek. Some nights the beefcake show made $25,000. Based on aNovember 13, 1984 deal with Steve Banerjee scribbled on a paperrestaurant napkin, Nick De Noia received half the profits from thetour shows. He was quickly becoming a wealthy man and, as a resultof his many media appearances, had become known as Mr.Chippendales.

That Tuesday afternoon in 1987 in New York, De Noiawas on his way to Indianapolis where the Chippendales werescheduled to perform. Just after 3:30 p.m., De Noia, in blue jeansand an open-necked, dark dress shirt with a white grid pattern,looked up from his desk to see a Hispanic male walk into hisoffice. The man was in his late thirties, neatly dressed in a darktan, waist-length jacket and blue jeans. He might have been the manwho had called a short time before to make a 4:30 appointment foran audition, but not only was he far too early for the appointment,he was also clearly no dancer. At 5 7 and 145 pounds, he was farshorter and smaller than the dancers De Noia hired. He also lookedill, his cheekbones protruding against his taut, pockmarkedskin.

Are you Nick De Noia? The manstone suggested this was not a question De Noia could refuse toanswer.

Yes, De Noiaacknowledged.

Youre a dead man then, thestranger said, pulling a 9 mm automatic handgun out of hiswaistband and leveling it at De Noias face.

De Noia rose from behind his desk. The choreographersmiled as if it was a joke, before a look of sheer panic crossedhis face. The stranger pulled the trigger and fatally shot De Noiaonce just below the left eye.

Chapter 1

Reaching for the American Dream

On November 19, 1973, with a borrowed $1,000, anIndian-American partner, and a recent Loyola Marymount UniversityLaw School graduate handling the legal aspects of the deal, SomenBanerjee signed an agreement to rent with an option to buy afailing nightclub in the Palms district of West Los Angeles: theRound Robin.

The moribund Round Robin was at 3739 Overland Avenuejust south of Palms Boulevard where the road narrowed and small,run-down businesses crowded the road before the street widenedagain at Venice Boulevard. The area was on the verge of beingseedy, dotted with garages enclosed by rusted chain-link fences andtwo-bedroom, single-story houses with sun-bleached paint, some ofwhich had been converted into small businesses and hole-in-the-wallrestaurants. The street was pot holed, its sidewalks cracked.

Outside, Overland lacked streetlights. Inside, theclub was dimly lit. The Round Robin boasted a tiny dance floor,which was usually empty. The crummy combo that masqueraded as aband probably drove more people away than they attracted. It was soquiet that Banerjees new attorney, Bruce Nahin, was studying forthe bar exam at the club because it was quieter than a library.

Banerjees future looked bleak. In the first twoweeks running the club, he and his partners went more than $5,000into the red. Banerjee worked hard to attract business. He changedthe clubs name to Destiny II, hung out a mammoth sign proclaimingthat the club was Under New Management, and held a grand opening.Since there were always more men than women at nightclubs, the keywas to lure women into the club and the men, like lions afterlambs, would follow, so he offered no cover charge and two freedrinks to all the ladies. It all helped, but not enough.

The new name, Destiny II, was meant to denoteBanerjees new future. When he arrived in Los Angeles, he hadbought a Mobil gas station, his first destiny; the club would behis second. Whatever his destiny, he had already come a longway.

Somen Banerjee was born into the fourth generationof a family of printers on October 8, 1946 in what was then Bombayand is now, under a more accurate pronunciation system, Mumbai,India. He emigrated from the West Indian port city to Canada andthen to the United States in 1969, ending up in Los Angeles. Likemany immigrants to the United States, he adopted a Westernizedname: Steve. Like most immigrants, the newly renamed Steve wascompetitive, with a phenomenally high need to achieve and a beliefin the American dream that put most native-born Americans to shame.Within a couple of years of arriving in the City of Angels, he hadbought a Mobil gas station in posh Playa del Rey, just north of LAXon the shores of the Pacific. He had far greater dreams, however,than just owning a gas station. America was the land of opportunityand he planned to seize every opportunity that came within hisreach.

Steve Banerjee was far from the stereotypical gasstation manager. Although he carried 160 pudgy pounds on a 5 9frame, Steve dressed for success. He wore large, at-the-timestylish glasses, colorful button-down Oxford shirts with silk tiesand dress slacks. Adding to his out-of-place appearance at the gasstation was his attitude, which betrayed at every opportunity hisbelief that his present work was far beneath what was going to behis true station in life. He was brusque with customers, showinghis resentment when they even just asked for the restroom key. Heread business journals and studied the work of his favoritedesigners and filmmakers, Giorgio Armani, Calvin Klein and StevenSpielberg, all the while dreaming of making it big in America. Heacquired the Round Robin with thoughts of turning it into a poshbackgammon club, reflecting his image of himself as a fashionablegentleman of means. When he adopted the name Steve, he alsoretained his given name of Somen, probably because in his nativeBengali, Somen is pronounced show-men. The sound of his namematched his dream of succeeding as a club owner.

Next page