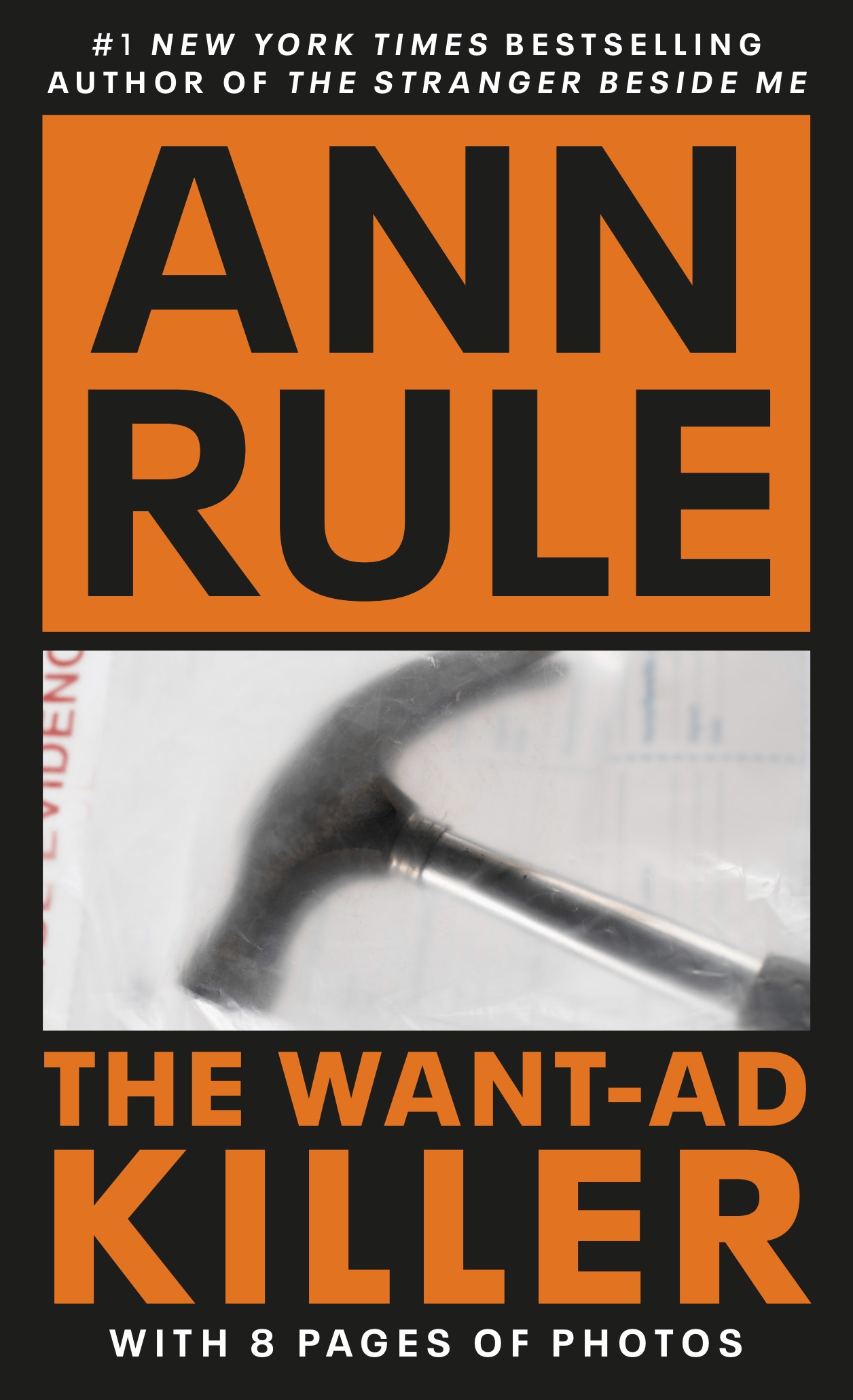

This book could not have been written without the help of the following individuals and organizations. Although recalling events was both onerous and painful for many of those who helped me, it is my hope that the resulting work meets with their approval. My sincere thanks to: Mary Miller, Linda Barker, Doreen Hanson, Sally Peterson, and Lola Lindstad of the Families and Friends of Missing Persons and Violent Crime Victims; Detectives Duane Homan, Billy Baughman, Dick Reed, Wayne Dorman, and Don Cameron of the Seattle Police Departments Homicide Unit; Detective Archie Sonenstahl of the Hennepin County, Minnesota, Sheriffs Office; and to George Ishii, director of the Western Washington Crime Lab. Special thanks go to Pierce Brooks, retired captain of detectives of the Los Angeles Police Department, and Robert Heck of the U.S. Department of Justice, designers of VI-CAP, the Violent Criminal Apprehension Program.

My appreciation to my editor, Michael Ossias, and my agents, Joan and Joe Foley.

And to Mike Prezbindowski, president of Systems West, whose skill provided me, finally, with a word-processing system!

Prologue

Mary Miller had a terrible nightmare in the late summer of 1957, a dream so real that she woke in terror in the humid heat of that New York City August night, a dream so full of the portent of evil yet to come that it clung tenaciously to the cobwebby places of the mind where conscious thought rarely surfaces. She would never dream that dream again, and yet she never really forgot it; it walked with her, whispering of tragedy, for the next fifteen years.

And then, just when she thought that it was really only a nightmare after all, it came true.

Mary Miller was twenty-five when the nightmare came, a young wife, a new mother. Only twenty-five, and yet she had already lived through disaster and loss, and somehow survived. When she was still Mary Purgalis, she had lived the comfortable childhood given to upper-middle-class European children before the Second World War changed everything. Born in Latvia, in a little town almost on the Russian border, to parents who were both highly respected judges, and cosseted by a close and loving extended family, Mary Purgalis, the child, knew only happy memories. With the invasive onslaught of the German and Russian armies, that life was blown away like dandelion fluff in a sudden wind.

When the war came, we had to leave Rigathe capital of Latviaand try to find a way west. The Russians came in, and then the Germans, and then the Russians again, and nothing was the same. We had tried to get to Sweden but we couldnt make the border, so we just kept heading west, walking, and riding coal trains when we could. We were all together, Mary recalls. I was a kid; I didnt really know how bad it was. My parents, my sisters and brother, my great-aunt, my grandmotherall of usheading for Dresden. But when we got there, Dresden had been flattened. We were supposed to leave on a boatbut it sank. There was little food. People think that hunger hurts, but it doesnt. After a while, you dont even notice; you only get sick when you have something to eat again.

Mary Miller skips over her war stories. They dont matter. What happened to Kathy was so much worse than anything that happened to me in the war. We werent in a concentration camp; we were in a displaced-persons camp. And then there was a sponsor who brought us all to America, to the state of Washington. We were all still together, and it was okay then.

Mary Purgalis started school at Clover Park High School in Tacoma, Washington, a stranger in a strange land where she barely understood the language. She had learned English in Latvia, but American English was different from what she had learned in textbooks.

I had enough credits to graduate from high school, but I had to learn to speak the language, so I took English and American history, and all the subjects Id never had before.

She learned rapidly; she was very bright, and even then had a strength, a resilience that belied her frail appearance.

I went to school with the children of the guards from the federal prison at McNeil Island. I thought that was as close as I would ever come to crime or violence in America. We lived on Anderson Island, a tiny island that lies just off Tacoma in Puget Sound. The last ferry back to the island was at seven P.M . We knew several Latvian doctors who worked at the state mental hospitalWestern Washington State Hospitalso if we wanted to participate in school functions in the evening or go to the movies, we slept over at the hospital. It didnt have the sexual offenders program then, of course. They were just sick, sad people.

I wasnt afraid.

After Mary Purgalis graduated from high school, she moved to New York CityBecause thats where I thought everyone went to seek their fortunes. She married, and on May 23, 1957, she gave birth to her first child: a daughter, Katherine Sue Miller.

Kathy was born in the French Hospital in New York. She was a beautiful, healthy blond baby.

The nightmare came when Kathy was four months old.

I dreamed that I had a daughter with long dark hair. She was fourteen years old in my dream, and someone had hurt her. There was blood all over her face. I couldnt tell if she was dead, but I knew that she was terribly hurt. There was so much blood, and try as I might, I couldnt help her....