In the long run, for my grandchildren

CONTENTS

Introduction

A Roller-coaster Reputation

John Maynard Keynes, 18831924

John Maynard Keynes, 19241946

3 In the long run we are all dead

Rethinking economic policy

4 Animal spirits

Rethinking economic theory

Epilogue

British and American Keynesianism

Introduction

A Roller-coaster Reputation

W HAT IF THE world is in depression again? Any talk of a slowdown now seems risible. Talk of a possible technical recession has come and gone. Even sound bites about the credit crunch do not measure up. Recession has been officially acknowledged meaning at least two consecutive quarters of decline in one after another of the major economies. So we have become accustomed to the phrase, from economists, business leaders and politicians alike, that this looks like the worst scenario since the Great Depression of the 1930s. But what if this is actually a depression of that magnitude? Whatever can we do about it? How on earth can we understand it?

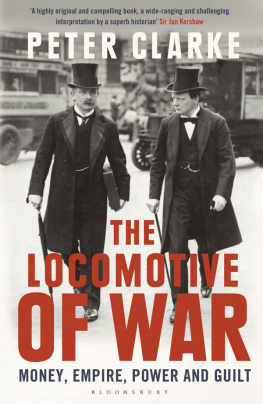

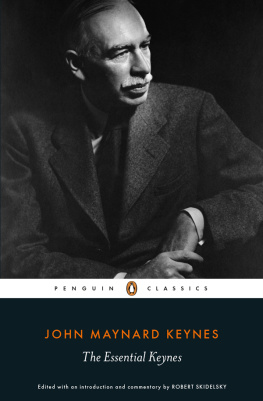

We can start by learning from what happened before. If we are short of ideas ourselves, we may have a new interest in the ideas that came out of the last epoch of depression, unemployment and uncertainty. One name above all keeps on cropping up, not only when economists discuss the situation but in the columns of British and North American newspapers and magazines, and in other media commentary. Often there is a grainy picture of a tall, stooped man with a pasty face, watery eyes, thinning hair and a heavy moustache, a half-familiar figure from a former era of worldwide economic depression an era that closed when the Second World War peremptorily intervened. Its Keynes, of course. But who was he and why does his thinking matter to us now?

His is an extraordinary reputation. Through nine decades, he has been celebrated, scorned, respected, appropriated, mocked, venerated, derided, rediscovered but seldom ignored. The name of John Maynard Keynes first came to wide public attention, on both sides of the Atlantic, in 1920. Still under forty, he became famous not as an academic economist but as the author of a sparkling and influential tract, published in London just before Christmas 1919. The Economic Consequences of the Peace focused public opinion on the defects of the recent Versailles Peace Treaty. Its account had an I-was-there immediacy, a magisterial detachment and a compelling plausibility. Had the British war leader Lloyd George, in his wily Welsh way, really bamboozled the upright Presbyterian President Woodrow Wilson about the impossible reparations demanded of the defeated Germans? For when Keynes dramatised the salient issues, this is how he cast the key figures and brought them to life. What he hoped to do for his readers and what he charged a belatedly penitent Lloyd George with failing to do for the sadly deceived President was to de-bamboozle them about what had really been going on behind the scenes.

The Economic Consequences of the Peace, a slim and readable volume, rapidly became an international bestseller. By April 1920, 18,500 copies had been sold in Britain. This was extremely good for a hardback by a hitherto unknown author, whose name had only crept into the small print of the London newspapers the previous year as one of Lloyd Georges Treasury aides at the Paris peace conference: an obscure Brit with a walk-on role in the negotiations, who appeared for the first time in the New York Times of 27 May 1919 as John M. Keynes a form of his name that he never used. Yet, within a year, the American edition of The Economic Consequencesof the Peace had sold 70,000 copies and the New York Times had given a full-page review to a book that was to be roundly denounced almost as often as it was eagerly purchased: in the English-speaking countries it is capable of doing immense mischief by still further clouding the issues of an epoch already sufficiently turbid.

Keyness capacity for immense mischief, far from being exhausted by this episode, was only just beginning. He had entered the world stage with a fanfare, prepared to brave the boos and catcalls of a hostile audience if need be, and he subsequently remained in the spotlight, not least in the United States. In London, he was to be mentioned in The Times in about sixty reports or editorials during the 1920s, and in about a hundred during the 1930s. Across the Atlantic, by comparison, his name appeared in the New York Times nearly 300 times in the 1920s a raft of references to a man whose subsequent career Americans followed with evident attention. Thus when the author of The Economic Consequences of the Peace, later in the 1920s, turned his lively mind and his deadly pen to the problem of unemployment, he already had a platform and an audience on both sides of the Atlantic.

Conditions in the stagnant British industrial system, however, were far different from those in the buoyant American economy, at least until the 1929 crash. As an economist based in the University of Cambridge, Keynes was naturally concerned primarily with the symptoms of depression in his own country. Conservatives liked to claim that protectionism offered a promising alternative, especially if tariffs could be used to bind together the British Empire. Like most economists, Keynes did not take this line, but nor was he happy with an orthodoxy that simply relied on market forces to do the trick. Instead, he boldly entered public debate with the contention that unemployment needed a drastic remedy.

Curiously, the politician whom he was supporting by the mid-1920s was none other than Lloyd George. The man who won the war, as propaganda for his coalition government had dubbed him in 1918, was the same man who lost the peace in 1919 or so TheEconomic Consequences of the Peace had famously argued. Lloyd George was now attempting a comeback, having himself come back to a reunited Liberal Party, of which Keynes was an active member. Has Mr Keyness opinion of Mr Lloyd Georges character changed since 1918? was the inevitable awkward question at one public meeting. The difference between me and some other people, Keynes suavely replied, is that I oppose Mr Lloyd George when he is wrong and support him when he is right. It was one among many subsequent occasions on which he was challenged for inconsistency. He never apologised for changing his mind when confronted by different facts or persuaded by better arguments.

Still the enfant terrible, then, Keynes made himself the spokesman for administering a stimulus when the economy was underperforming. We can see it as the launch of a Keynesian agenda that is still debated today. He called the prevailing system one of individualism and laissez-faire and attacked it accordingly. Laissez-faire, said Keynes, had done its work. He claimed that it now meant superstitious faith in the market as an end in itself, whereas the actual situation cried out for experimental devices as a means of promoting recovery. In the Britain of the mid-1920s this orthodoxy relied on the self-acting mechanisms of the Gold Standard and Free Trade to do the trick in the long run.

No, said Keynes, coining one of his most famous phrases: Inthe long run we are all dead. Keyness policies can thus be damned out of his own mouth as short-term expedients that saddle future generations with the inexorable costs of defying the market.

Such arguments came to a head with the decision to put Britain back on the Gold Standard in 1925. Winston Churchill was responsible for this, as Chancellor of the Exchequer. As a layman, he struggled to find his way through a technical argument that he recognised as central to the way that the economy worked. He argued and he listened. Keyness advice was politely listened to; then politely dismissed. The return to gold meant that the pound sterling was, in effect, shackled to an exchange rate of US$4.86. To Churchill, this meant being shackled to realities. To Keynes, the new parity was both completely unrealistic and perfectly avoidable, as was implied by the title of his polemical pamphlet: The Economic Consequences of Mr Churchill (1925).

Next page