From the Republic of the Rio Grande

Number Thirty-five

Jack and Doris Smothers Series in Texas History, Life, and Culture

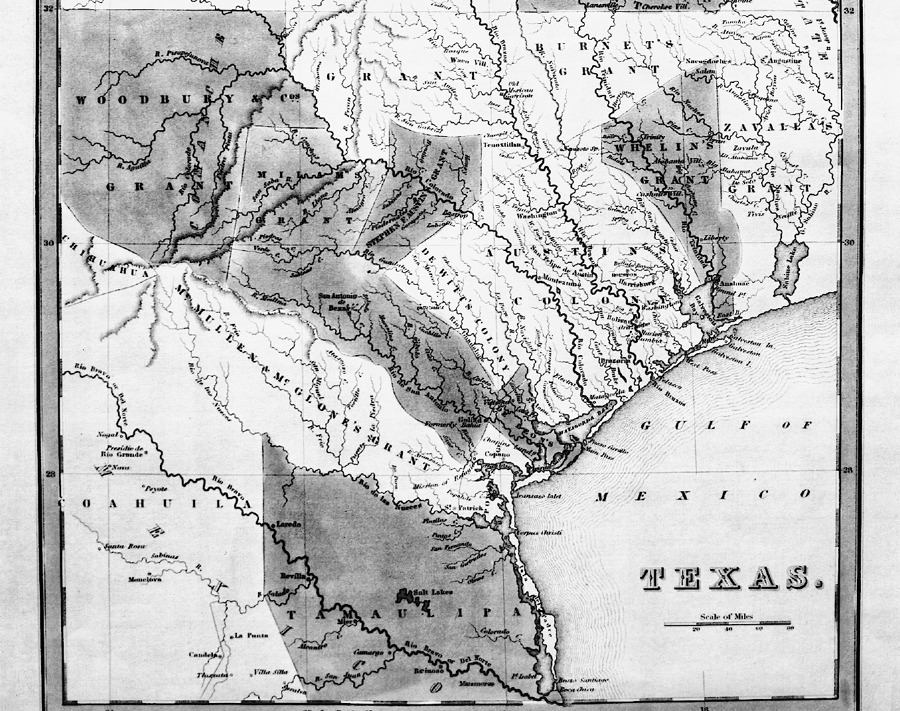

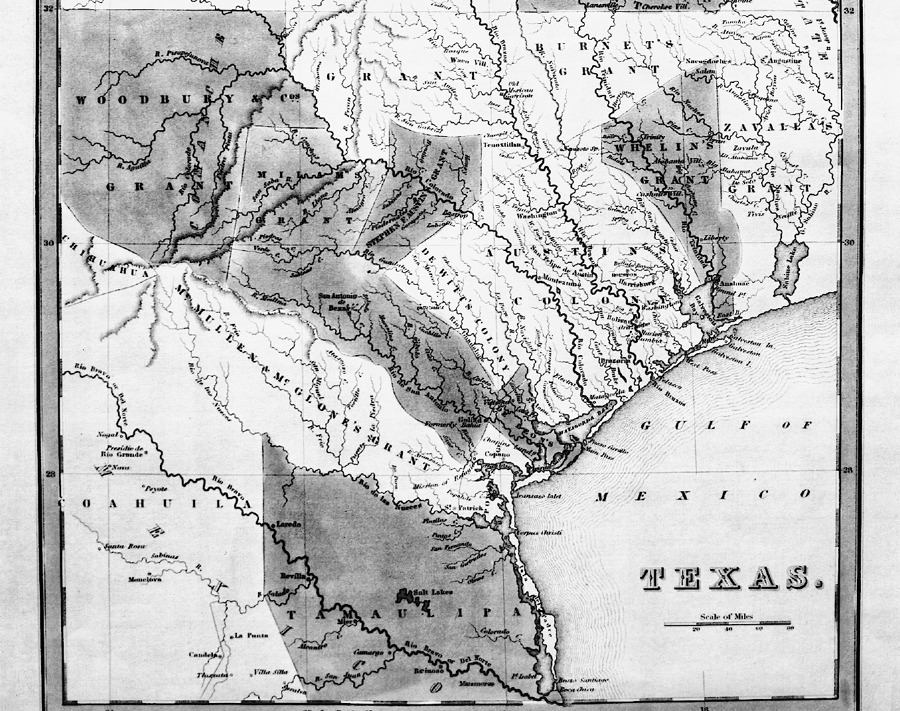

Texas, Coahuila, and Tamaulipas, circa 1833. Courtesy of the Austin History Center and Austin History Center Association, Austin, TX.

B EATRIZ DE LA GARZA

From the Republic of the Rio Grande

A PERSONAL HISTORY OF THE PLACE AND THE PEOPLE

University of Texas Press

AUSTIN

Publication of this work was made possible in part by support from the J. E. Smothers, Sr., Memorial Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

All photos not otherwise attributed belong to the author.

Copyright 2013 by Beatriz E. de la Garza

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First edition, 2013

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to:

Permissions

University of Texas Press

P.O. Box 7819

Austin, TX 78713-7819

http://utpress.utexas.edu/about/book-permissions

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

de la Garza, Beatriz Eugenia.

From the Republic of the Rio Grande : a personal history of the place and the people / by Beatriz de la Garza. 1st ed.

p. cm. (Jack and Doris Smothers series in Texas history, life, and culture ; no. 35)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-292-71453-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Mexico, NorthHistory. 2. Mexico, NorthHistoryAutonomy and independence movements. 3. Texas, SouthHistory. 4. Mexican-American Border RegionHistory. 5. de la Garza, Beatriz EugeniaFamily. 6. de la Garza, Beatriz Eugenia. 7. Mexico, NorthBiography. 8. Texas, SouthBiography. I. Title.

F1314.D44 2013

972.1dc23

2012024688

doi:10.7560/714533

ISBN 978-0-292-74407-3 (e-book)

ISBN 978-0-292-74876-7 (individual e-book)

Y ha de morir contigo el mundo tuyo,

La vida vieja en orden tuyo y nuevo?

(And is your world to die with you,

The old way of life you made anew?)

Antonio Machado, from Galeras

Contents

Preface and Acknowledgments

This book had its origins in a small trunktwenty-two inches long by eleven inches wide and high and made of tin reinforced with wood stripsfilled to the top with papers either generated or preserved by my paternal grandfather, Lorenzo de la Garza. Among the first were dozens of typewritten copies of his personal and business correspondence on flimsy onionskin, dating from the first third of the twentieth century, as well as original replies to that correspondencefor example, a brief (printed) thank-you note from the recently elected Mexican president, Francisco Madero, dated November 1911. The second group, on more durable rag paper and either printed or in the flowing copperplate script of the nineteenth century, consisted of official documents, such as deeds to family lands signed by President Porfirio Daz in the 1880s and correspondence on a variety of topics. Included in this correspondence were several letters relating to the deaths of two heroes of Mexican independence, Colonel Bernardo Gutirrez de Lara and his brother, Father Antonio, whose dual biography (Dos hermanos hroes) my grandfather wrote in the early part of the twentieth century. At the bottom of the trunk lay the heaviest items, mostly sepia-tinted portraits on stiff cardboard, known as cartes de visite, of family members in stiff collars that gave their heads a haughty tilt and colorful postcards commemorating travels or special occasions.

My grandfather lived most of his life (and died) in Ciudad Guerrero, Tamaulipas, a small town founded in the middle of the eighteenth century as part of a chain of settlements known as Las Villas del Norte along the lower Rio Grande. Grandfather Lorenzo died in 1948, five years before Ciudad Guerrero was flooded by the construction of Falcon International Reservoir, and its inhabitants were relocated to a new town. How the small trunk made its way from Guerrero Viejo (Old Guerrero) to Guerrero Nuevo, when neither my grandfather (who was dead) nor his daughters, who had already moved to Laredo, Texas, were there to supervise its transport, remains a mystery, but the trunk ended up in the new town, together with miscellaneous items, in the storage room of my maternal grandparents house. There I found it, some fifteen to twenty years after my grandparents death. Nobody else was interested in old papers, so I carried it off to Austin, Texas, where it came to rest in my storage room, undisturbed, for some ten years. During that decade of repose, the paternal papers were joined by others from the maternal side that a young family member found stored in a ranch building. But the best was yet to come: my collection of family papers was finally complete when my sister gave me the letters exchanged between our parents during their courtship, letters that she had kept till then. These letters, from the late 1930s and early 1940s, detailed the joys and sorrows of the lovers, proving that, indeed, the course of true love never did run smooth. In addition to revealing the hopes and aspirations of the writers, these letters introduced me to my parents, whom I had barely known, particularly my mother, who died when my sister and I were barely toddlers.

For years I figuratively sat on this wealth of family history without daring to delve into it. On the one hand, I was daunted by the practical considerations of sifting through the great number and variety of materials that would require, not only that I put them into some sort of order, but also that I make provisions for their conservation. For example, the oldest item in the trunk was a military appointment made by Mexican viceroy Francisco Venegas in 1812, and my parents letters were, of course, priceless. On the other hand, I feared that poring through the contents of the small trunk and the boxes that had joined it later was dangerously akin to opening Pandoras box. My fears were that, upon my lifting the trunks lid, myriad memories and feelings would fly out that would never be contained again. And indeed it turned out to be so, for as I read those old letters and documents, their authors came back to life through their words and resurrected their world with them. It was a world that had existed in a particular placethe northeastern Mexican states of Coahuila, Nuevo Len, and Tamaulipas (which then extended into South Texas, up to the Nueces River), a region oriented toward but not divided by the Rio Grande/Bravoand at a particular time, roughly bracketed between the middle of the eighteenth century and the middle of the twentieth. This was the world that had existed in the land that came to be known (rightly or wrongly) as the Republic of the Rio Grande.

Much like an archaeologist who reconstructs a lost civilization from the fragments of broken pottery found buried in the earth, I took these fragments of paper, long buried in the tin trunk, and worked to extract from each the stories that they contained. They were stories of personal milestonesweddings, births, and deathsall happening within the framework of historic events, such as wars and revolutions, as well as times of recovery from the periodic strife. They were stories that deserved to be told; however, for these stories to rise above being merely a collection of anecdotes and form a coherent picture, they needed to be connected to the broader events of the time and the places in which they occurred. To accomplish this, I had to go beyond the materials that I had and consult not only the orthodox sources for the history of the region, but also privately published local histories and memoirs, which often provided details that the more general and academic works did not. In going from the particular narratives gleaned from the family papers and the personal recollections that I gathered to the broader accounts contained in history books, I have attempted to flesh out the world and the times only glimpsed in those individual documents and stories, while, at the same time, giving history a human face.

Next page