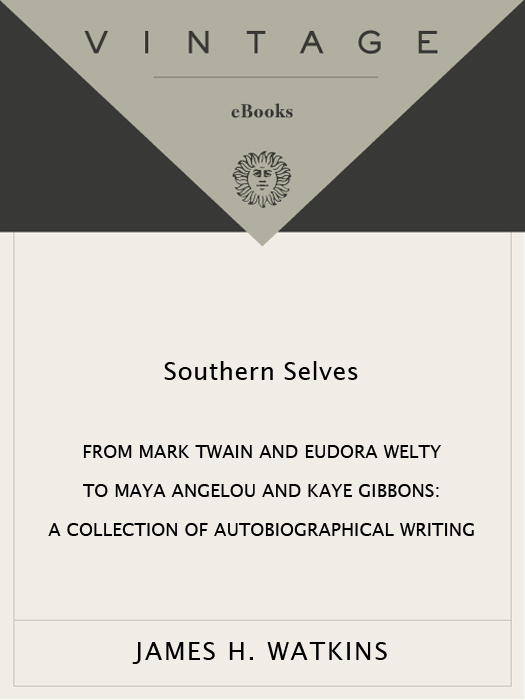

A VINTAGE ORIGINAL, AUGUST 1998 FIRST EDITION

Copyright 1998 by James H. Watkins

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States of America by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Southern selves : from Mark Twain and Eudora Welty to Maya Angelou and Kaye Gibbons : a collection of autobiographical writing / edited and with an introduction by James H. Watkins.

p. cm.

A Vintage originalT.p. verso.

eISBN: 978-0-307-42790-8

1. Authors, AmericanSouthern StatesBiography.

2. AutobiographiesSouthern States.

3. Southern StatesBiography.

I. Watkins, James H.

PS 551. S 575 1998

810.9975dc21

[B] 97-50206

constitute an extension of this copyright page.

randomhouse.com

v3.1

For Susan, Will, and Sam

Acknowledgments

I WOULD LIKE to express my appreciation to the following individuals who helped make this book a reality: First of all, Kaye Gibbons encouraged me to write the prospectus for Southern Selves and put me in contact with the right people after hearing my idea for the anthology. Anne Goodwyn Jones introduced me to a number of the works included in this collection in her graduate course on southern literature at the University of Florida, then enthusiastically agreed to direct my dissertation on southern autobiography. Four student research assistants at Berry CollegeTereasa Lowry, Crys ONeal, Nathan Hilkert, and especially Alicia Clavellprovided invaluable secretarial support as I waded through the copyright permission acquisition process and other potentially engulfing frustrations. Finally, this book would not have been possible without the generous guidance and support I received from LuAnn Walther and Diana Secker at Random House.

Contents

Introduction

F OR MORE THAN a century, the American South has been recognized as a region blessed with a wealth of literary talent and subject matter. While that reputation has been based primarily on its many fine novelists and short story writers (and, to a lesser extent, its poets), southern soil has also proven fertile ground for the flowering of a rich autobiographical tradition that is stronger today than it has ever been. The same deep-rooted sense of place that allowed William Faulkner to create his microcosm of the South, the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, has also provided the impulse and materials for southern autobiographers and memoirists to present their lives, and to do so in ways that call attention to their intimate knowledge of place. As Eudora Welty has written, Place absorbs our earliest notice and attention, it bestows on us our original awareness; and our critical powers spring up from the study of it and the growth of experience inside it.proof to Weltys claim, providing an occasion for the author to reflect upon the ways in which his or her identity has been shaped by its attachment to a specific southern locale.

But place signifies much more than mere geographical location. When William Alexander Percy begins Lanterns on the Levee: Recollections of a Planters Son with the words, My country is the Mississippi Delta, the river country, he implies that his sense of personal identity is intimately intertwined with both the physical and cultural landscape of the Delta, with its rhythms of speech, its patterns of social interaction, its historyeven its cuisine. Thus, in order to fully appreciate the degree to which the selections in this anthology present located lives, we must pay attention to the subtle links that are drawn between the lay of the land and the manners of the people who inhabit that land. Nevertheless, not all of the writers represented in Southern Selves identify so easily as Percy seems to with the communities into which they were born. Strict and often violent enforcement of the racial status quo and (to a lesser though no less pervasive extent) rigid expectations concerning gender roles and class position remind us that place can also connote a fixed position in a racial or social hierarchy. Therefore, many of the selections in Southern Selves represent the authors effort to reject the place he or she had been assigned. Paradoxically, such an effort requires the author to describe in a convincingly detailed manner the ways in which individuals are kept in their places, and in order to accomplish this he or she must speak as an insider, one who is intimately familiar with the full range of his or her home communitys methods of social control.

No group has had more at stake in resisting its place in the South than African Americans, whose literature has its primary sources in the slave narrative. The basic plot pattern of oppression, acquisition of literacy, then flight to the North that can be found in the writings of Frederick Douglass and Harriet Jacobs has been mirrored in the lives of so many other southern-born blacks that its narrative structure can be traced in most of the classic writingsfiction as well as non-fictionby African Americans. Although most autobiographies by African Americans conclude with the narrators escape from a benighted South, resistance to white racism takes other forms as well, one of which is the strong bonds formed within the African-American community. From Zora Neale Hurstons Eatonville, Florida (according to Hurston, the first incorporated all-black township in the U.S.), to Maya Angelous Stamps, Arkansas, to Clifton Taulberts Glen Allan, Mississippi, we find close-knit communities held together in times of joy and adversity by storytelling, feasting, and, most importantly, religious worship.

Though their situation was vastly preferable to that of most African Americans, many white female autobiographers and memoirists have used life-writing as an opportunity to articulate their frustrations with the rigid expectations concerning gender roles in the traditional South. In fact, the assumption that southern ladies did not engage in public discourse stifled the development of an autobiographical tradition among this group of southerners until the beginning of the twentieth century, long after women in other parts of the country had found public voices. From turn-of-the-century suffragist Belle Kearney to literary iconoclast Evelyn Scott to antisegregationists Lillian Smith and Katherine Du Pre Lumpkin, we find privileged women who struggle against patriarchy by deconstructing the image of the southern belle and exposing the paternalistic logic that had positioned them as desexualized icons of white southern culture. Nowhere is the task of toppling the image of the southern belle handled with such biting humor as in Florence Kings aptly titled Confessions of a Failed Southern Lady, where we observe a grandmother who polishes silver daily, worshiping at the altar of southern shintoism and obsessing about the family tendency to fallen wombs.

If many of the white female writers in this collection have an axe to grind about the restrictions placed on women in southern society, quite a few of the white autobiographers, male and female, focus their attention on the negative effects of racism in the South. Perhaps the most noticeable pattern to be found in the autobiographies of white southern liberals is the confessional motif, in which painful memories of past racist sins are recounted as acts of expiation. Lillian Smith describes a long-repressed traumatic event from her childhood in which she was forced to recognize the hypocrisy of her parents profession of Christian values, while Willie Morris writes with unflinching honesty about the race-baiting he and his friends would engage in between baseball games and other forms of amusement. For Tim McLaurin, the recollection of a childhood interracial friendship becomes the medium in which he explores his own complicity in southern racism.