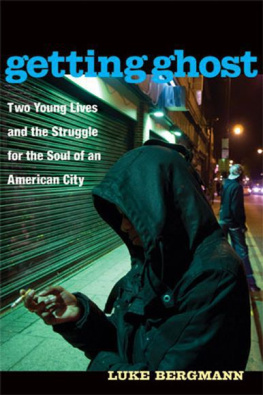

Getting Ghost

Two Young Lives and the Struggle for the Soul of an American City

LUKE BERGMANN

THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS

Ann Arbor

Copyright 2008 by Luke Bergmann

Published by the University of Michigan Press 2010

First published by The New Press 2008

All rights reserved

Published in the United States of America by

The University of Michigan Press

Manufactured in the United States of America

Printed on acid-free paper

2013 2012 2011 2010 4 3 2 1

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978-0-472-03436-9 (paper : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-472-02640-1 (e-book)

In Loving Memory of Ron Gu's

Contents

Acknowledgments

Over the past several years, as my own personal life has gone through a significant transformationculminating with the birth of my beautiful son, Esaithe stories and lives in Getting Ghost have been constant companions. Many of the central characters in the book, whose names I've changed, will probably be the most eager readers of this narrative. It is to these folks, of course, that I owe the greatest debts of gratitude. This text is woven out of their experiences and lives. And for their willingness to bring me into the most intimate corners of their world, for their courage, respect, friendship, and faith, I am so grateful.

This book began a number of years ago as a doctoral dissertation in the Department of Anthropology and the School of Social Work at the University of Michigan, and many people at Michigan helped me along the way. Tom Fricke, in whom I discovered a shared obsession with James Agee, encouraged me to work beyond the disciplinary conventions I'd been trained to observe. Beth Reed, Rosemary Sarri, Carol Boyd, and Bill Birdsall were all guardian angels for me while I was living in Detroit. Janet Finn, Alford Young Jr., and Fernando Coronil helped me get my head straight at various points. And for their support, encouragement, and kindness about my fledgling efforts to do this work, I want to thank John Ramsburgh, Jeffrey Shook, Alex Ralph, Sebastian Matthews, Greg Harris, James Reische, and Sarah Munro. Skip Rappaport was also in my mind and heart as I was working on Getting Ghost. I hope it does not disappoint him.

At the University of California at San Francisco and Berkeley, I have benefited from the advice and guidance of Philippe Bourgois, Deborah Gordon, Paul Rabinow, Jeff Schonberg, Kelly Knight, Nick Bartlett, and Laura Schmidt.

Irene Skolnick believed in this book from the get-go and secured the perfect home for it. I feel so fortunate that The New Press exists. Andy Hsiao got support for the manuscript at The New Press, and Furaha Norton has been heroic in making it a clearer, better told story. Needless to say, I bear full responsibility for any of the text's shortcomings.

This work could not have been completed without financial support from the University of Michigan Substance Abuse Research Center, the Rack-ham School of Graduate Studies and the Advanced Study Center at the University of Michigan, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Institute for Health Policy Studies at the University of California at San Francisco, and the Prevention Research Center and UC Berkeley School of Public Health. I am grateful to all.

For my family, this project has shadowed me like a second life. All six of my wonderful sisters have lent their sympathetic ears and helped me to stay centered. Andrea Sankar has been an important source of intellectual and logistical help. Aunt Renee McCoy took me in and continues to inspire me. Taya Nelson picked me up when I was falling apart on many occasions and has consistently steered me toward deeper explorations of the emotional dimensions of this work. Eric Nelson has enriched this project with good humor and warm support. Frithjof Bergmann has been, for many years now, my closest and most valuable intellectual ally. Jessie Flynn was accommodating and loving throughout the many years that I spent in and around Detroit. And finally, Rosemary Polanco has been a pitch-perfect editor, brutally honest sounding board, and incredible mother to our lively son as the book has gone through its final trimester. It is so rare that any of us find someone whose opinion and judgment we implicitly trust. I am lucky indeed.

Dramatis Personae

EAST SIDE

Dude Freeman, Family, and Friends

Dude Freeman 16-year-old East Sider

Ruby Mother

Forrester Older brother

Felicity Older sister

Evelyn (Evie) Older sister

Elvin Evie's twin

May Oldest sister

Lydia Paternal aunt

Marvin Father

Dude's Friends

Billy

Chewie

Treb

Aisha

Janet

Walker

Detention Facility

Cedric Mann

Branford Wilson

Fredrick Nelson

Bosworth

Raul

Willis Harrison

Justin

Bernardo

Ms. Bailey

Mr. Mallard

WEST SIDE

Rodney Phelps, Family, and Friends

Rodney Phelps 19-year-old West Sider

Maria Mother

Antonio Younger brother

Julie Older sister

Princess Older sister

Annie Girlfriend

The Dexter Boys

Sheed

Kilo

Loc

Hector

Shell

Ebo

Oscar

Timmy Mason

Rabbit

Jeremiah

Z

Dante

Marley

Coney Island

Larry

Mikey

Polly

Patty

Household on Pingree

Esther

Juwan

Benjamin

Dwayne

1

Introduction

Many die too late, and a few die too early.

The doctrine still sounds strange: Die at the right time!

Friedrich Nietzsche, Also Sprach Zarathustra

BIFF : He had the wrong dreams. All, all, wrong.

HAPPY : Don't say that!

BIFF : He never knew who he was.

CHARLEY : Nobody dast blame this man. Nobody dast blame this man.

A salesman is got to dream, boy. It comes with the territory.

Arthur Miller, Death of a Salesman

Having escaped the fires, they trudged in tattered, soot-stained clothing toward a busy street where they might find help. Somewhere, a keen-eyed photographer for the Detroit Free Press captured the young black family, the morning after the first day of rioting in the city, as they walked with their few salvaged belongings underneath a row of smoldering brick chimneys, which shot through the collapsed houses around them.

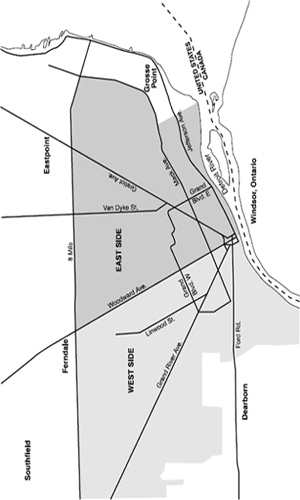

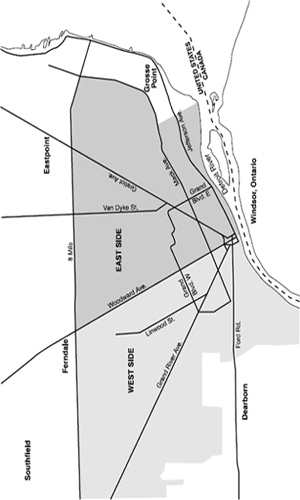

Though the riots of summer 1967 spread from one corner of Detroit's interior to the other, consuming building after building on the East and West Sides, and up and down some of the city's most bustling streets, the houses shown burning in the Free Press photograph, just off Linwood Street between Pingree and Blaine, represent the center of what would be the city's most devastating residential damage. Nearly the entire square block burned down after wind-borne embers from a nearby business landed on the roofs of several houses.

Over thirty years later, when I moved into the bottom floor of a two-family flat on Pingree, in one of the spared homes across the street from what had been this residential conflagration, the chimneys were long since toppled and cleared away, and a city park had been made of the vacant field left by the fire. Now, when I stood on the worn oak floor in my room and looked out the window, I could see chain-link softball backstops facing each other from the corners of the park and a wavy asphalt basketball court that had been built off to the side.

Printed on acid-free paper

Printed on acid-free paper