This story is dedicated to the men and women of the coalition forces who have fought in Afghanistan, and to their families and loved ones, many of whom have come to realize that not all battles end with the war.

Ten good soldiers, wisely led, will beat a hundred without a head.

Euripides

I met Hamid Karzai, the president of Afghanistan, at the Barclay Hotel in midtown Manhattan on September 23, 2008, when he was approaching the end of his five-year term as the countrys first democratically elected leader. Since 1700, twenty-five of the twenty-nine rulers of Afghanistan had been dethroned, exiled, imprisoned, hanged, or assassinated.1 That Karzai had survived multiple assassination attempts since taking office was a feat in itself. Even more remarkable, however, was the journey that had brought him to this presidency.

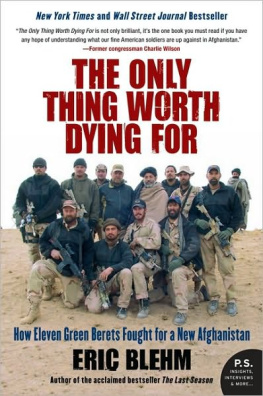

He greeted me in perfect English with a British accent, shook my hand firmly, and ushered me across the elegant room of his suite. Though it was Ramadan, when Muslims fast from dawn to sunset, he offered me cookies and coffee or tea, which I declined out of respect for his religion. Sitting opposite the president in a cushioned armchair, I handed him a stack of photographs. As he held them in his palms, he stared intently at the one on top: eleven American soldiers grouped tightly around him on a sandy hillside in southern Afghanistan. A smile spread over his face, and he began to nod as he flipped through the pictures chronicling the mission that had changed the course of history.

For nearly two years, I had been trying to interview Karzai so that he could confirm crucial details of his rise to power during the early days of the Global War on Terror, a war that Karzai and his staffwho had joined us in the room to hear their president tell his storiescalled by another name: the Liberation. He transported us to the mud-walled safe houses of his insurgency, where, lit by kerosene lanterns, turbaned freedom fighters with AK-47s planned strategy with U.S. Special Forces soldiers wearing camouflage. He led me through the photos, which I had placed in chronological order, taking us back to October, November, and December 2001.

I was concerned that he might not be able to recall details about the men who had sacrificed so much for both America and Afghanistan in carrying out one of the wars most dangerous and secretive missions. I wondered whether all that he had experienced in the ensuing years had erased or distorted his memories.

Then he held up a photo to his staff and pointed to an American soldier. Had there been anybody else, things would have gone terribly wrong, he said. A mournful tone now entered his voice. Oh, some good men

Very sad, he said about the next photo. This is perhaps a day or two before he died. Looking closely at the following photo, he said, This man is dead. And this manhe is also dead. And this man.

When? I asked. Do you remember the date they died?

Of course, he answered. How could I forget?

The following is a true narrative account of modern unconventional warfare as recalled by the men who were there. Some names have been changed to respect the privacy of the individuals.

A Most Dangerous Mission

[H]e knew from experience how simple it was to move behind the enemy lines. It was as simple to move behind them as it was to cross through them, if you had a good guide.

Ernest Hemingway, For Whom the Bell Tolls

Late on the night of Tuesday, November 13, 2001, Hamid Karzai and his military adviser, U.S. Special Forces Captain Jason Amerine, walked briskly down a deserted road near their safe house in the Jacobabad District of Sindh Province, Pakistan. For Amerine, it felt almost as if they were walking along a country road stateside, the adjacent unplanted fields softly illuminated by starlight. In the distance, a half mile to the west, a dull glow marked more densely populated civilization, but here they were relatively isolated.

Karzai was unarmed and wearing the traditional Afghan shalwar kameez , and his poise and flowing arm motions marked him as an orator. Tall and thin, Amerine had an M9 pistol tucked into the belt of his camouflage uniform. Above a coarse brown beard, his alert eyes never stopped scanning the dark fields while he and Karzai spoke in hushed tones.

I just received confirmation, said Amerine. Tomorrow is the nighthave you heard any news from the tribal leaders in Uruzgan?

Yes, said Karzai. I followed up with one of the local chiefs in War Jan. If the location we decided upon is safe, if no Taliban patrols are nearby, the signal fires will be lit as planned.

Your men are ready?

They areword has spread about Kabul. The Pashtun are ready to join the fight.

Earlier that day, allied U.S. and Northern Alliance resistance forces had liberated Kabul, Afghanistans capital, from the Taliban. That was in the north; in the south, the home of the majority Pashtun ethnic group and the birthplace of the Taliban movement, things werent going so well. Neither the CIA nor the U.S. military had been able to establish a presence, and there was no organized resistance like the Northern Alliance. The few Afghans who dared to oppose the Taliban had been imprisoned or killed.

For four weeks beginning in early October, Karzai had traveled the region unarmed, trying to persuade leaders throughout the Pashtun tribal belt to rise up against the Taliban. The CIA considered this undertaking so dangerous that it refused to put any men on the ground with Karzai, limiting its involvement to giving him a satellite phone so that a case officer could monitor his progress. By the end of October, Karzai and a small group of followers had been pursued by the Taliban into the mountains of Afghanistans Uruzgan Province. Using the phone, he called for help on November 3 and was rescued by a helicopter-borne team of Navy SEALs.

Though hed been chased out of Afghanistan, Karzai told the CIA that the Pashtun in the south were ready to rise upif he returned with American soldiers who could organize and train them into a viable fighting force.

Only a few individuals were supposed to know that Karzai was now in Pakistan, so it had shocked and angered both Karzai and Amerine when U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld disclosed Karzais whereabouts to the media during a Defense Department press briefing earlier that week. Rumsfeld recanted what he called his mistake a couple of hours after he made it, telling the press that while Karzai was being assisted by U.S. Special Forces (Green Berets), he was somewhere in Afghanistan, not in Pakistan.

Amerine and Karzai feared that the Pashtun would interpret the news that Karzai was in Pakistan as a sign of weakness. Every village elder, Taliban deserter, and farmer who might otherwise support him could withdraw their backing or, even worse, turn on Karzai. In order to maintain credibility within the Pashtun tribal belt, he and Amerine would return to Afghanistan on the most dangerous and politically important mission thus far of Operation Enduring Freedom.

Now, walking down the center of the gravel road, Karzai and Amerine were reviewing the plan for the following nights mission, when the eleven members of Operational Detachment Alpha (ODA) 574, Amerines Special Forces A-team, would be the first American team to infiltrate into southern Afghanistan. There, they would link up with the Pashtun tribal leaders and villagers who had promised Karzai allegiance.

The purpose of this mission was twofold: destroy the Taliban in the important southern city of Kandahar, where they were expected to regroup after the fall of Kabul; and unite the southern Pashtun tribe with the northern Tajiks, Uzbeks, and Hazaras. The Northern Alliance was on course to topple the Taliban, so unless the Pashtun joined the fight, they would be frozen out of the government that would rule after the Taliban. If this happened, Karzai was convinced that Afghanistan would descend into another devastating civil war.