Authors note

Excerpts from the memoir have appeared in The Healing Muse (Shocked, 2008; Undercover Agent, 2011), The MacGuffin (Pay Attention, 2008), The Common (At the Y, 2012), Literal Latte (The Other Chair, 2013), and Southern Humanities Review (Good Humor, 2014).

The events recounted are authentic and described to the best of my ability. Some names have been changed for purposes of confidentiality and privacy.

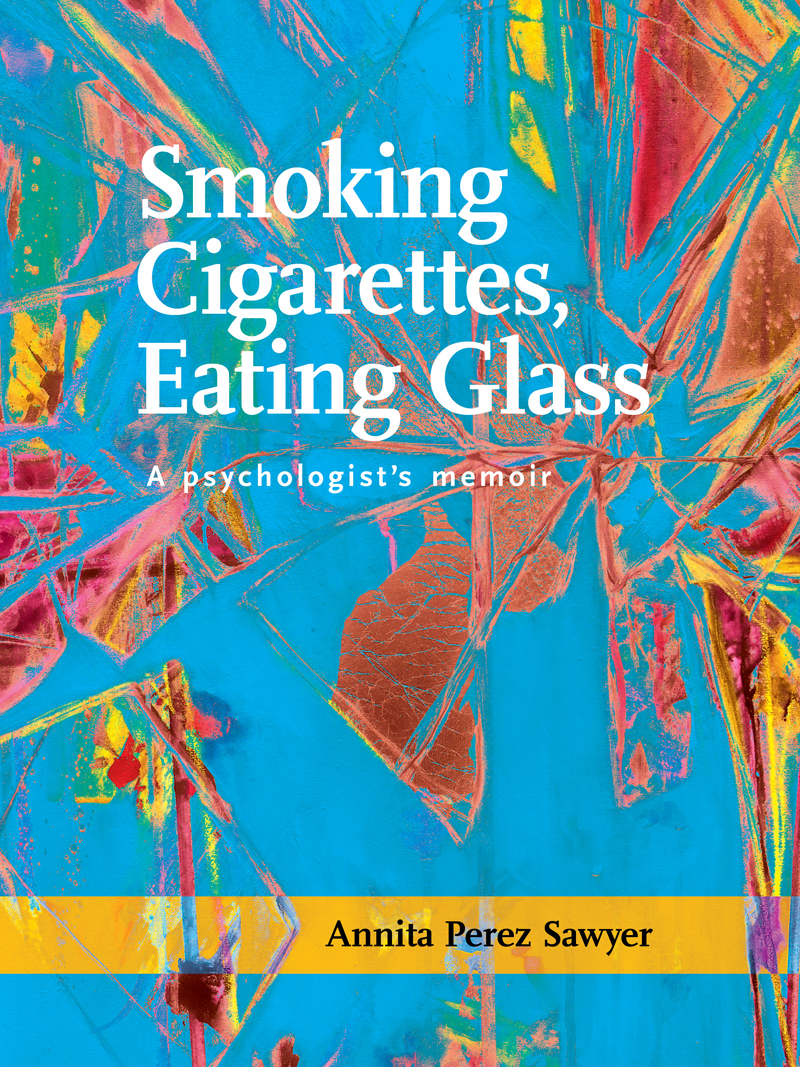

Copyright 2015 by Annita Perez Sawyer

All rights reserved.

First Paperback Edition

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sawyer, Annita Perez.

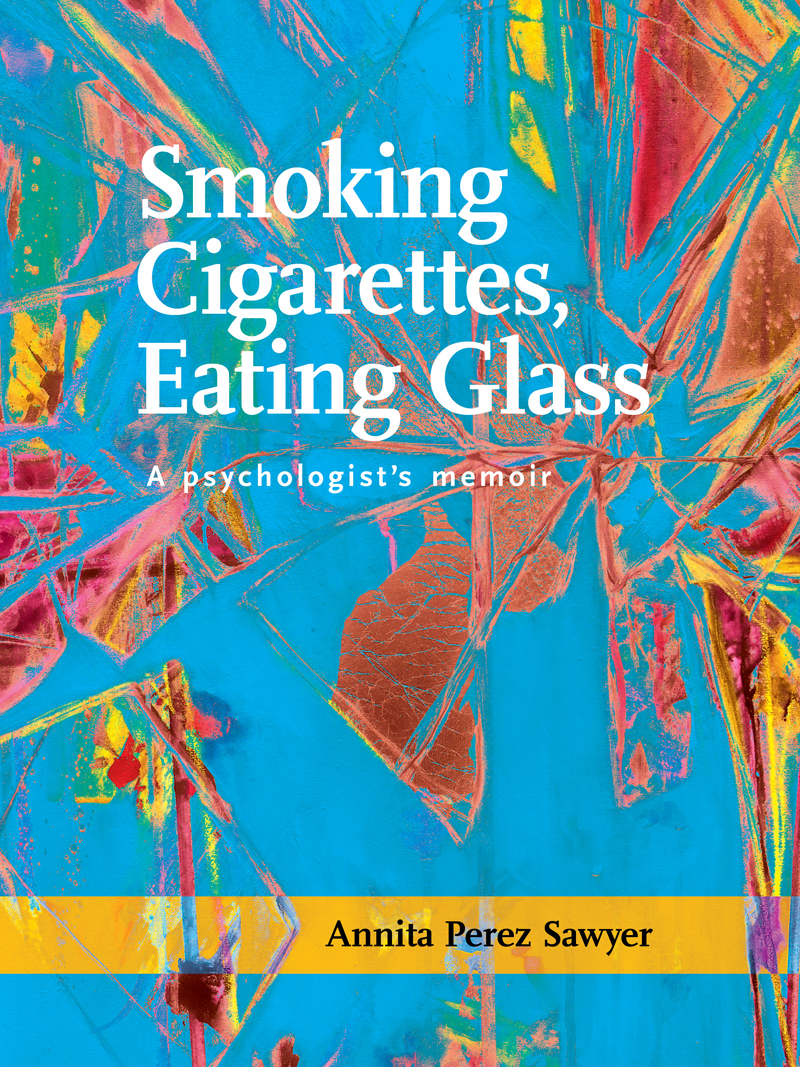

Smoking cigarettes, eating glass : a psychologists memoir / Annita Perez Sawyer, PhD. First paperback edition.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-939650-26-9 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Sawyer, Annita PerezMental health. 2. Mentally illUnited StatesBiography. 3. PsychologistsUnited StatesBiography. 4. Psychiatric hospital careUnited StatesHistory. 5. Psychiatric errorsUnited States. I. Santa Fe Writers Project. II. Title.

RC464.S29A3 2015

616.890092--dc23

[B]

2014026915

Published by SFWP

369 Montezuma Ave. #350

Santa Fe, NM 87501

(505) 428-9045

www.sfwp.com

Cover image: Erica Harney; detail from Annita in Mind

www.ericaharney.com

Find the author at www.smokingcigaretteseatingglass.com

Contents

To all children, young or grown, who could not speak and were never known; to all healers with courage to pay attention; to all families and friends who would help if they could understand; and to everyone who has believed in me.

I have woven a parachute out of everything broken

William Stafford

PROLOGUE

Pay Attention

April 2004

H a nds on the large round wall clock hesitated, then lurched forward, ticking each minute away. The meeting had started late; it was time for me to speak. I gathered my stack of notes in front of me, patting the edges smooth. I straightened my shoulders and moved a wisp of hair away from my eyes. Two-dozen mental health professionals stared at me where I sat in their midst at a square oak table in the crowded conference room. A small woman across from me, a world-famous psychoanalyst, smiled in a reassuring, grandmotherly way. The director nodded, Go.

My message of transcendence is myself, I began, working to keep my voice full. Me. Alive. Here. I speak as a seasoned psychologist, and I speak as a woman who was a patient in this institution for several years when I was young.

I glanced up. The analyst smiled again. For a moment, I sparkled.

Id arrived early, making my way from the parking lot with the help of a map scribbled on the back of an envelope by the psychiatrist who had invited me to attend. Walking in, Id scrutinized the faded carpets on the old wooden floors, the juxtaposition of windows and walls, the ceilings odd angles, wondering if Id ever been in this particular building before, one of many in this well-known mental hospital complex known informally as Bloomingdales. I was struggling to remember when Id been a teenager locked in here decades earlierbeyond all the shock treatments that erased most of my memory, beyond the doctors who gave up on me before I was twenty.

Id worked on my presentation for weeks, writing and rewriting what I wanted to say. Id practiced in front of mirrors. Id recorded myself with a video camera and critiqued the tape on my TV. I might never have an opportunity like this againI had to set them on fire.

I glanced at the men and women seated at the table and lining the edges of the room. Large and small, stylish and frumpy, young clinicians and interns sprinkled among renowned analysts and researchers. I was a thin, ordinary-looking, late-middle-aged woman with trifocal glasses and short hair. Outwardly, I appeared no different from them. Might there be others like me hidden here? I wondered.

Beside me sat the white-haired man, a few years older than myself, who had arranged for me to come. We had first met almost forty years earlier in another hospital when he was a young psychiatrist in training. I had been an inpatient on his unit. Are they expecting a doctor or a patient? A speck of anger gleamed like dust on a sunbeam. For a moment I was seventeen again, shivering, naked, rough wet sheets wrapped tight against my skin, lying on a gurney in the hall with the smell of sour sweat hovering in a cloud around my head.

My face burned. I ran a hand through my hair, forcing myself back into the present .

I was dressed in a gray Brooks Brothers suit I had found at the outlet, my favorite velvet scarf draped around my neck. A freshly polished leather briefcase my husband had given to me when Id earned my PhD over twenty years earlier kept my feet company, resting beneath the chair. It held pages and pages of what I wanted to say, probably enough for twenty presentations.

I rubbed my thumb across a tiny silver basket pinned to my lapel, then over the silver ring on my little finger. My children had made them, with their fathers help, when they were young. Could I have imagined this scene back then? I raised my head and straightened my spine.

Forty years ago, I was a patient here, I continued. I endured years of terrifying treatment for the wrong diagnosis, treatment that made me worse. In the end, I was transferred out for lack of improvement. A surge of energy rage? fear? joy? swept through me, catching me off guard. Under the table, I clasped my hands together as tightly as I could, so as not to fly apart into pieces. I began to tell them my story.

I described shrinking in high schoolmy handwriting becoming so tiny it was illegible; my voice increasingly inaudible ; my body, like my spirit, withdrawing from the world and closing in on itself. I told them about my diary heaped with guilt and self-loathing. About my suicide plans. I quoted the doctors assessments directly from hospital notespatronizing and degrading descriptions of myself.

Then I described my shock treatment and the fear that the electricity inducing the seizures would kill me. I explained that when Id failed to improve, my doctors had prescribed even more. At this, the elderly hospital director winced. His sad eyes shrank into faraway, dark points as creases in his face deepened around them. I felt myself lift out of my bodyfor a moment I didnt know who or where I was.

Should I stop? I asked him.

No, no. Please continue, he said, his voice gentle, as if he recognized my distress.

After three years at the first hospital, I was transferred. My diagnosis: Dementia Praecox (schizophrenia); my condition: Unimproved . Another year passed before I was assigned to a psychiatrist who could see me as an individualas a person, not a syndrome. When I made stupid puns, he laughed. When I told him that evil garbage stank and should be eliminated, he told me he knew someone who found treasures in garbage. One persons stink is anothers perfume, hed said, astonishing me. No longer utterly alone in the universe, I grew curious about myself and how I worked. My interest in the outside world expanded. I began to heal.