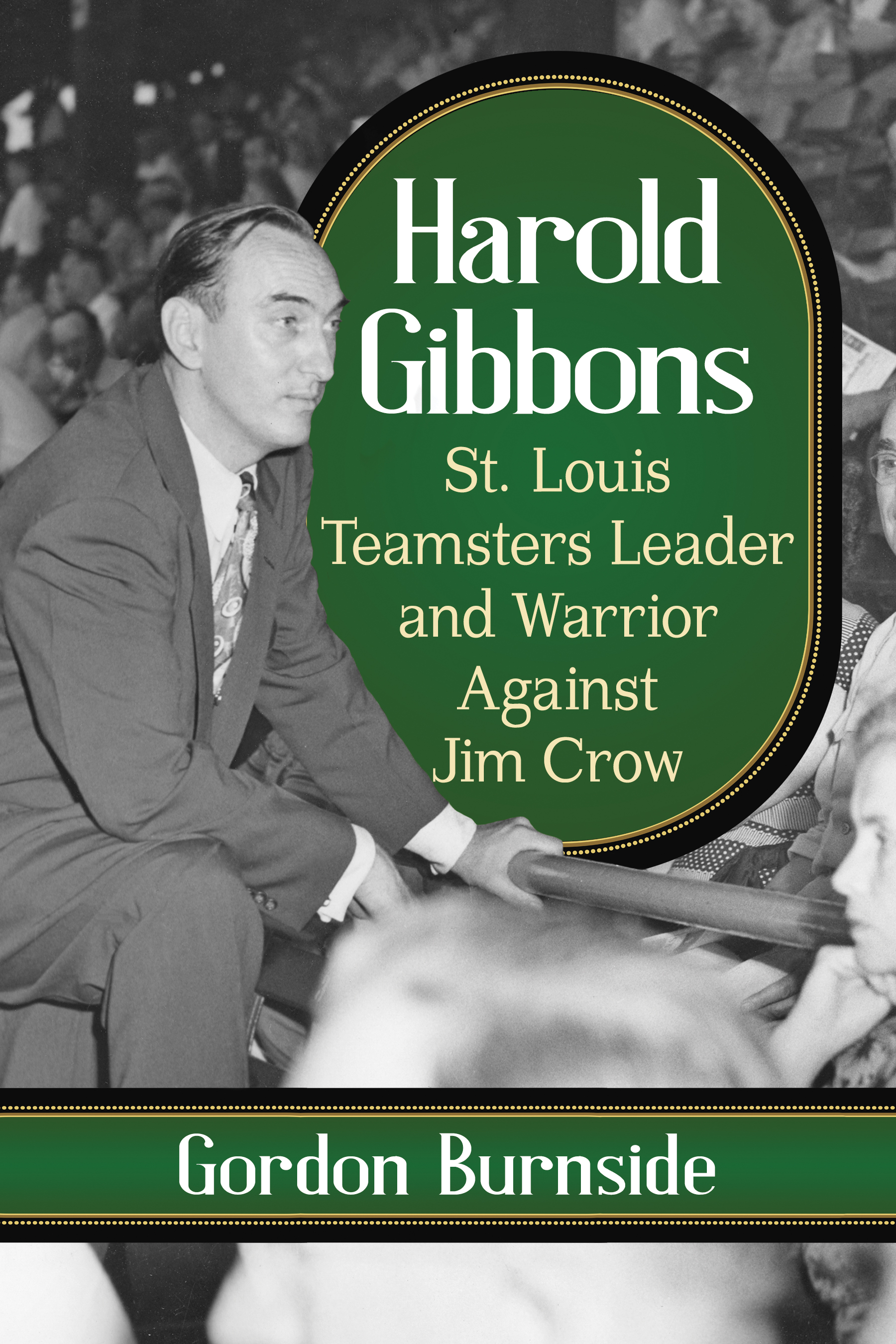

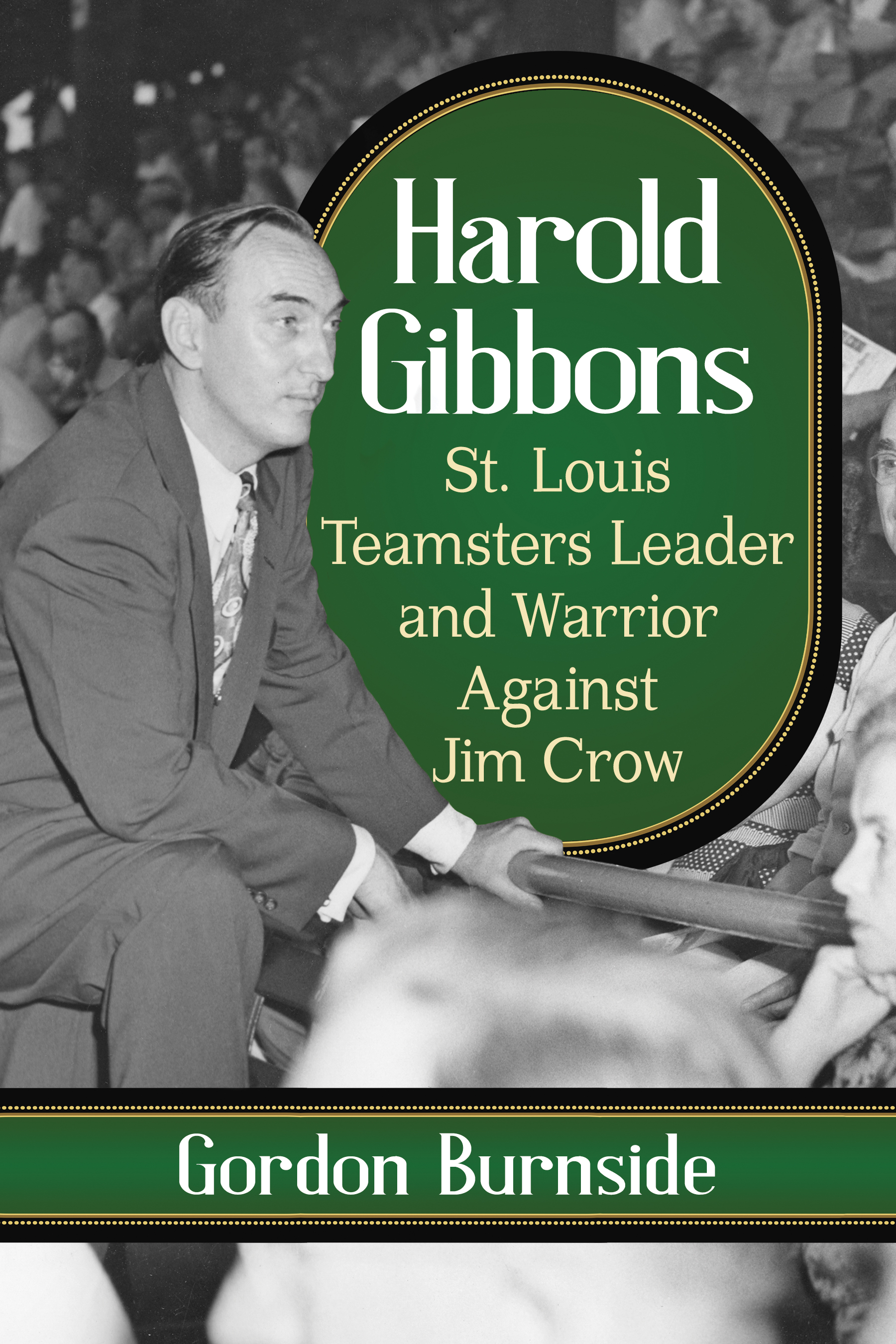

Harold Gibbons

St. Louis Teamsters Leader and Warrior Against Jim Crow

GORDON BURNSIDE

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN:978-1-4766-3366-4

2018 Gordon Burnside. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover image of Gibbons and members of the union enjoying a night of baseball at Sportsmans Park, 1940s (Blanchard Studio, Bellevue, Illinois, 559.43, State Historical Society of Missouri, Photograph Collection)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

In memory of my mother,

Mary Myers Burnside,

who taught me to love books

A Note on Terminology

Teamsters Local 688, the main labor organization discussed in this book, is a local union. It is an affiliate of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, or IBT, which is an international union as opposed to a merely national one. International unions are so-called because they have affiliated local unions in a foreign country. In nearly all cases, the foreign country is Canada.

The IBT refers to its top officers as the general president, the general secretary-treasurer, and members of the general executive board (which is constituted by the first two plus a dozen or sothe number variesvice presidents). In this book, for simplicitys sake, those officers are called president, secretary-treasurer, and members of the executive board.

Books like thisconcerning trade unions and other organizations, laws, regulations, official boards, etc. tend to get crammed with acronyms and initialisms. Ive tried to hold them to a minimum, but the following seemed unavoidable:

AFLAmerican Federation of Labor

AFSCMEAmerican Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees

CIOCongress of Industrial Organizations

CORECongress of Racial Equality

IBTInternational Brotherhood of Teamsters

ILWUInternational Longshore and Warehouse Union

LHILabor Health Institute (Local 688s medical clinic)

NLRBNational Labor Relations Board

RICORacketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act

RWDSURetail, Wholesale, and Department Store Union

SACspecial agent in charge (FBI)

UAWUnited Auto Workers

UEUnited Electrical Workers

UMWUnited Mine Workers

Introduction:

A Word or Two About Gibbons

I came to St. Louis and discovered the most creative local union in the nationErnest Calloway

In late 1946 or perhaps early 47, the St. Louis labor leader Harold Gibbons went to Chicago in search of a female organizer for his union. The majority of Gibbons members were warehouse workers, and mostly men, but he was hoping to add people working in the next step up in the commercial-goods chain: sales clerks in the citys big department stores, most of whom were women.

In Chicago he found Bernice Fisher. A russet-haired, thirty-year-old white woman, Fisher, though not beautiful, was so lively that she trailed admirers, male and female, behind her. She was indeed a professional trade union organizerbut that was, as we say nowadays, merely her day job. Her chief interest in life lay in dissolving barriers between the white and black races. Fisher and a handful of friends at the University of Chicago had a few years earlier formed a group they called the Congress of Racial Equality, or CORE. With CORE as their organizational vehicle they set out to integrate restaurants, lunchrooms, bowling alleys, and other businesses that even in Northern cities routinely refused service to African Americans.

Fishers group was little known outside Chicago except to scattered left-wingers like Harold Gibbons. Twenty years later CORE, along with two other direct-action groupsMartin Luther King Jr.s Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)would spearhead the movement that finally eradicated legal racial discrimination in America. (Casual discrimination, as everyone knows, remains.)

But that was in the 60s. Not 1947.

In St. Louis Bernice Fisher began signing up salesladies in Gibbons union. Evenings she spent building a local chapter of CORE. For it she recruited a high school teacher, a one-legged war veteran, a sociologist, a historian of the worlds religions, a future federal judge, various others, all of whom shared her sharp sense of revulsion when in the presence of racism. The new CORE group began tackling downtown eating places where discrimination reignedwhich, St. Louis being then an essentially Southern city, was nearly all of them. COREs philosophy was Christian-pacifist (Bernice Fisher was a Baptist). Its members dressed in their Sunday best and treated adversaries with respect. They would begin a campaign against, say, a restaurant that refused to serve blacks by first negotiating with the owner; then, if talks failed, leafletting passers-by on the sidewalk outside; and finally, if leaflets proved unavailing, sitting-in at the counter. Sometimes a campaign failed completely and CORE would move on temporarily to another business. All this required fortitude and time. Indeed, it took a full decade. But, scrupulous in its methods and trusting in its notion of justice, St. Louis CORE eventually got the job done. By the early 1960s, when the rest of America was just awakening to the movement for civil rights, CORE had defeated Jim Crow in downtown St. Louis.

Harold Gibbons meanwhile tried to keep mum about ties between his union and CORE because some of the merchants whose workers the union hoped to organize, especially owners of the department stores, werent above suggesting to such workers that their so-called labor union was really a bunch of fanatic race-mixers. Still, the connection was there for all who cared to see. CORE held meetings at the unions headquarters and used its equipment, especially the vital (in those days) mimeograph machine. Gibbons hired a number of CORE activists to serve on the unions staff and he himself sat for years on COREs national board. (He quit when the integrationist organization went black nationalist in the late 60s.)

A word or two here about Gibbons. His dates are 19101982. He was a big, athletic man, handsome in a bust-of-a-Roman-senator way, especially after he began to lose his hair. His parents were Irish immigrants who had settled near Scranton, Pennsylvania, the father laboring as a coal miner. The family was large and poor. Gibbons father died when Harold was a boy, after which the family moved to Chicago. There the son planned to make his fortune. I was going to be an engineer and I was going to be a rich guy, he told a biographer.

Instead, he fell in with a species of American we would today call liberal but which in the 1920s and early 30s often combined principles learned in the Progressive movement with membership in the Socialist Party. In Gibbons case such people were often women, usually immigrants, frequently Jewish, and either industrial workers or trade union officials a couple of steps up from the assembly line. These wise women tutored Harold in the skills needed for a union career, particularly public speaking. Under their guidance he became a very effective stump orator as well as an imaginative and aggressive tactician.

Next page