ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

T here are numerous people we would like to thank for helping to make this book come to fruition, beginning with the loved ones of the subjects of each chapter. We recognize that your loss will never go away, but we hope that, in writing about the individual's death, we have portrayed what made each of them so memorable in life. It's an honor to be able to share with readers what we have learned, and perhaps to also provide you with some measure of comfort.

Deep praise goes to our executive editor, Linda Greenspan Regan, for her excellent suggestions and skill; our tireless copyeditor, Julia DeGraf; and to the rest of the fine team at Prometheus Books, who are both professional and considerate.

We give a fond salute to Dr. Wecht's office staff for unfailing support and good cheer, from Florence Johnson and Darlene Brewer, to Sigrid Wecht, Esq., whose legal and administrative acumen are always top-notch.

Special mention for research and encouragement goes to Brett Bush and Mark Nardone, Caseen Gaines, Debra Storch, Treva Silverman, and Zia Shields. And for particular assistance on the chapters that concern them: Jos Baez, Esq.; Tracy Shue, Jason M. Davis, Esq., George Brown, and Roger Anderson; Geoffrey Giuliano, and Jeff James of Dick Clark Productions; Joel A. Brodsky, Esq.; Chris, Mimi, and Corey Bechen, Jennifer Martin, Greene County (Pennsylvania) district attorney Marjorie Fox, first assistant district attorney Linda Chambers, and witness coordinator Cherie Rumskey; Noah, Ella, Nathaniel, and Tobias Gotbaum, and Michael C. Manning, Esq., Leslie O'Hara, Esq., and Anne L. Slawson of Stinson Morrison Hecker LLP; Brian Oxman, Esq.; and Kevin O'Sullivan of AP Images.

Finally, much gratitude is extended to our family members and friends, whose excitement in reading our work is eclipsed by the inspiration they have provided to us.

AFTERWORD

I f there is one thing we hope you have gleaned from the cases in this book, it is that forensic science is not black and white. It's not even lovely shades of gray. Forensic science is a glorious rainbow of color and light, with new hues constantly being discovered on a regular basis.

In the olden days, death investigators depended on fingerprints and blood typing to target and identify suspects in criminal matters. That was certainly a step up from eyewitness accounts, the predominant method of the past, which were wholly unreliable in practicality. The need for more precise training evolved, expanding to ballistic testing; dental and X-ray comparisons; shoe and tire impressions; handwriting analysis; and microscopic inspection of trace evidence, such as hair and fibers. Eventually our federal government established a computerized database to store samples of various forensic tools, allowing a detective in any community to tap into the national bank of research to quickly seek matches or information.

The mid-1980s saw a significant upgrade for crime solvers with DNA testing, in which the nucleic acid in cellular structures is analyzed to reveal genetic patterns from human semen, vaginal secretions, sweat, tears, saliva, and skin cells. By obtaining a noninvasive swab from the inside of a person's mouth, authorities can compare it to a known sample from a crime scene or a victim to find similar markers. Now a mainstay for law enforcement, DNA testing has its own national database where an expert, using a few keystrokes, can scroll through millions of contributors to find a match, and new donations are constantly added to the system. When presented in court, and explained to a jury by a scientist with impeccable expertise, the results can link, or clear, a suspect in a homicide or major criminal matter. DNA can be used to send a defendant to death row, or to spring a wrongfully convicted inmate from prison.

The chapters we've recounted here have featured an array of exciting new features of forensic science:

- Cell phone technology, using global-positioning signals from cell towers to track the location and activities of an individual, as well as separate GPS tracking of vehicles;

- The ability to collect and separate distinct elements in air samples, including odors from food, gasoline, dirty diapers, dead animals, and human body decomposition;

- Inspection of a hair shaft for signs of possible post-mortem banding and toxicological segmental hair analysis to determine a time frame for a person's drug ingestion;

- Analysis of the qualities of duct tape and plastic bags to determine when and where they were manufactured and sold, and comparing them to items a suspect or associate might have had access to;

- Re-creations of crime scenes to assess the plausibility of a suspect's story, or to show the position of a body when discovered;

- The effect of nature on a corpse, from temperature and meteorological conditions, to insect and animal activity, and soil and foliage samples;

- Computer forensics, from determining the author and the time and date of an e-mail or text message, to copying and preserving the content of a hard drive, without falling into a booby trap that will delete critical data, and;

- The importance of tissue sample reviews using a high-powered microscope to find or eliminate pre-existing disease as a contributing factor to someone's demise, among other techniques.

As this book goes to press, two of our seven cases have not yet been tried before a jury, but you now have a strong indication of what kind of evidence and testimony will be presented in court.

Beyond these cases, other crime-fighting systems are in use or on their way to gaining acceptance in our nation's courtrooms, including facial-recognition and age-advancement software, satellite imagery that can reproduce photos as small as a license plate number, marking gunpowder and explosive materials, linguistic analysis to measure patterns of speech or writing, voice and sound enhancement, identifying DNA in animals and plants, and calibrating the pressure one uses when applying pen to paper to determine authorship of a questioned document. These methods nicely complement the legwork that detectives do in gathering human intelligence and the intriguing behavioral analysis from the FBI's esteemed profiling unit. And there is always the dramatic push-pull between police, prosecutors, defense attorneys, and the media.

These cutting-edge breakthroughs are valuable not only to law enforcement but also to film and television scriptwriters, who turn the thrilling actual scenarios into fantastic cinematic projects. Whether it's real life, or reel life, there's a never-ending quest to use science as a means of telling stories.

We can only imagine what the future of forensic science will be. But it's gratifying to know that there will be a steady stream of interested students scaling new heights of intelligence and excellence.

Cyril H. Wecht, MD, JD

and Dawna Kaufmann

CHAPTER ONE

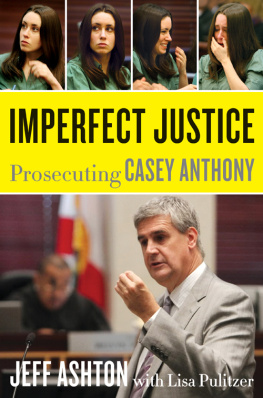

CASEY ANTHONY

Big Trouble Comes in Small Packages

F or years to come, law enforcement students will study this case because it spans a number of forensic disciplines, from pathology, anthropology, entomology, and laboratory work to police investigation, behavioral science, and legal strategies. At its center, the case against Casey Marie Anthony should be about a wrongful death. But the road to justice has proven most circuitous, with the jury's verdict as controversial as the crime itself.

On June 15, 2008, in Orlando, Florida, it was said that a bitter showdown took place between Casey and her fifty-year-old mother, Cynthia, a nurse better known as Cindy. Cindy and her husbandCasey's father, George, fifty-seven, a retired Ohio detective working as a security guardlived with their daughter and granddaughter, Caylee Marie, who was almost three. Cindy was criticizing Casey's parenting skills, and Casey was arguing back loudly. At one point, Cindy said she would fight for custody of the baby and allegedly put her hands around Casey's throat. Out of deference to George, who reminded the women that it was Father's Day, they ended the fracas, but the next day, Casey was still furious. While Cindy was out of the house, Casey told her father goodbye and said she was going to work. As she left, she was holding little

Next page