Copyright 2010 F+W Media, Inc.

Krause Publications, a division of F+W Media, Inc.

700 East State Street Iola, WI 54990-0001

715-445-2214 888-457-2873

www.krausebooks.com

Introduction

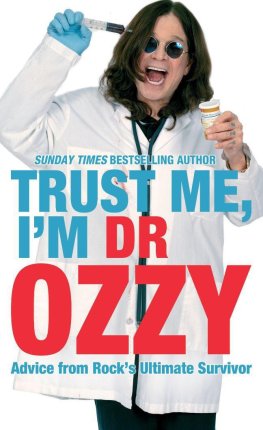

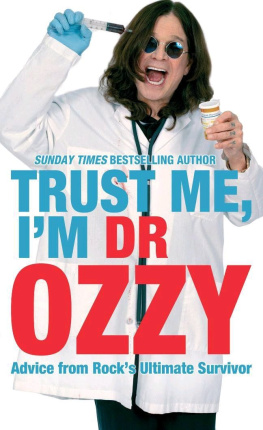

Bubbles! Oh come on Sharon! I'm fucking Ozzy Osbourne,I'm the Prince of fucking Darkness. Evil! Evil! What's fucking evil about a shit load of bubbles!

Search for Ozzy Osbourne on the Internet, and chances are that remark will be one of the first hits you get. Because, more than all the millions and millions of words that have been written about him, those fractured sentences uttered by him best sum up the sheer dichotomy of the man.

To many people, those who have followed his career since 1970, or have picked up on his music in the four decades since then, Ozzy is the Prince of Darkness, a man whose music has sound tracked so many demonic fantasies that, if it's true what they say about the Devil having all the best songs, then Ozzy's been stuffing his jukebox for forty years.

To those who discovered him through The Osbournes reality show, though, he's a family man as well, one who may act crazy when the cameras are on, but who really likes nothing better than to settle down with his family, watch TV, and then relax ina bubble bath? Well, maybe not.

This book is about both of those personas, and a handful more besides. It depicts Ozzy from every angle: the family man and the Prince of Darkness, the politician and the sex object, the drunkard, the druggie, and the epitome of sobriety. It is about rock n roll and how it can save your soul, and modern life and how it damns it. There will be moments of laugh-out-loud comedy, and scratch-your-head craziness. He will deliver some shocking confessions, then turn around and confess that he's shocked. There will be moments of deep introspection, and tenderness, too.

But most of all, there will be Ozzy, pure and unadulterated, four decades worth of his ripest ripostes, oddest observations, deepest dreams, and most articulate answers. Yeah, articulate. Because he might come over like a crazy person when you watch him on TV or hear him on the radio, but when you sit down and seriously consider what he's saying

Well, he said it best. He's fucking Ozzy Osbourne. And he's got a few things to tell you.

But first

First, I'd like to tell you a story.

Riffing on the name of one of Britain's best-loved candies, Ozzy Osbourne shrugged disdainfully in the early 1980s: The nearest Sabbath ever came to Black Magic was a box of chocolates.

At the end of 1968, however, it was difficult for anybody, confirmed chocoholic or otherwise, to avoid some reflection on the Dark Arts. Scything out of the psychedelic underground as it searched desperately for fresh alternatives to the rules of the establishment, the successor (logical or otherwise) to the Beatles' drive into transcendental meditation, Satanism was the counter-culture's next big thrill and, from the Sunday tabloids to the Rolling Stones opposite poles that had hitherto rarely agreed on anything it lay correspondingly upon everybody's lips.

We have become very interested in magic, Stone Keith Richard warned the Sunday Express. We are very serious about this.

And there was more. Study the faces arrayed on the Beatles' Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band sleeve, and influential English occultist Aleister Crowley peers out from there as well. British blues legend Graham Bond, whose Organization band proved the seminal training ground for some of the later 1960s' greatest instrumentalists(Cream's Jack Bruce among them), was a loudly practicing occultist; and Jimmy Page, at that time guitarist with the Yardbirds (but later to fly Led Zeppelin to glory), had friends all over the world seeking out diabolic literature for his personal library. It was already common knowledge that the Devil had all the best music. Now it seemedas though he had all the best musicians as well.

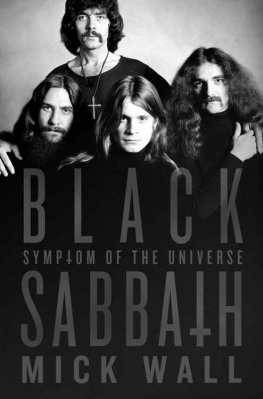

It was guitarist Tony Iommi who first voiced aloud the thought that his band, Earth, could do a lot worse than attach their own star to the underworld firmament.

Iommi, vocalist Ozzy Osbourne, bassist Geezer Butler, and drummer Bill Ward had already been playing together for a couple of years, during which time Earth had developed a great reputation around their native city of Birmingham, England. But that was all they had, a reputation and the dubious honor of Iommi having spent four days as a member of Jethro Tull at the end of 1968.

What they needed now was something to transform that reputation into reality;something that would make people sit up and pay attention. Glancing out at the cinema that stood across the road from the band's garage rehearsal space, watching the queues of customers patiently awaiting whatever was showing that week, the quartet mused aloud about how it was always the horror films that drew the longest lines. It was the age of the Hammer Studios' greatest epics, the seemingly endless litany of variation son Bram Stoker's Dracula; but, equally, it was an age that had been irrevocably flavored by the success of Roman Polanski's Rosemary's Baby, a genuinely frightening film that didn't simply tap into the prevalent counter-culture zeitgeist; it stormed it in a manner that the likes of the Rolling Stones could only dream of.

Neither was it the cinema alone that was making money hand-over-cloven hoof, nor merely the music industry that was so delightedly dancing with the devil. For every unreformed hippy kid who still sat in a park, his nose buried in The Hobbit or the I-Ching, there were now three times as many fearlessly devouring the works of Dennis Wheat ley, the greatest of all Britain's pulp occult authors. From the war pigs snuffling in the trough of Vietnam, to the hollow hell of starvation and famine in Biafra, civilization itself was bracing for an encounter with the Dark Lord, and Osbourne couldn't help but wonder: if people were willing to pay good money to be scared by a movie or a book, how much would they pay to be scared by a rock band?

Earth had already driven their sound into a dark, almost stygian, cavern, a bludgeoning of enormous riffs, a tsunami of bass and percussion and, over it all, a vocal that shrieked and whooped like a banshee. It was a primeval sound, one that seemed to predate even the most barbarous rock 'n' roll in its unerring reduction of its component elements to one solid wall of slow-moving, gut-shaking, heart-haunting noise.

But the further Earth moved away from the standard blues and rock 'n' roll covers that were their regular repertoire, the further their chances of finding an audience seemed to recede. If they were to succeed, they needed to begin again same sound, same musicians, but a very different name and a very different image. Osbourne's horror rock idea was a sound one, to be sure. But, according to Ward, it was still a major decision.