Prologue

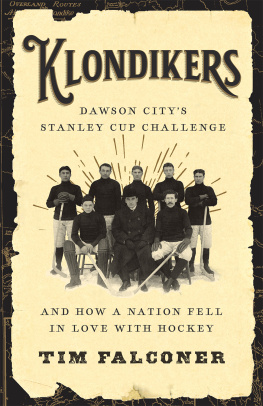

The Canadian Pacific Railways Continental train was nearly three hours late when it pulled up to the station in Winnipeg. Given what the hockey players had been through since leaving the Klondike, this barely counted as a complication. After all, inconvenient forces had started conspiring against them even before they headed out of Dawson City. First, one of the teams stars decided to stay behind with his injured wife. Then the captain and most accomplished player realized he had to stay a little longer for work. Hed try to catch up with others as soon as he could. The teams luck did not improve once the journey began.

Setting out to capture the Stanley Cup, and the fame that went with it, the players figured it would be a straightforward eighteen-day trip. Straightforward by Yukon standards, anyway. Three left on foot on December 18, 1904; four others followed on bikes the next day, though they all eventually abandoned their wheels. After 330 miles, the team arrived in Whitehorse two days after Christmas, only to watch a blizzard shut down the narrow-gauge trains on the White Pass & Yukon Route Railway. When they finally reached Skagway, Alaska, theyd missed their steamer to Vancouver by two hours and had to wait days to board a Seattle-bound ship for a voyage that left the players severely seasick.

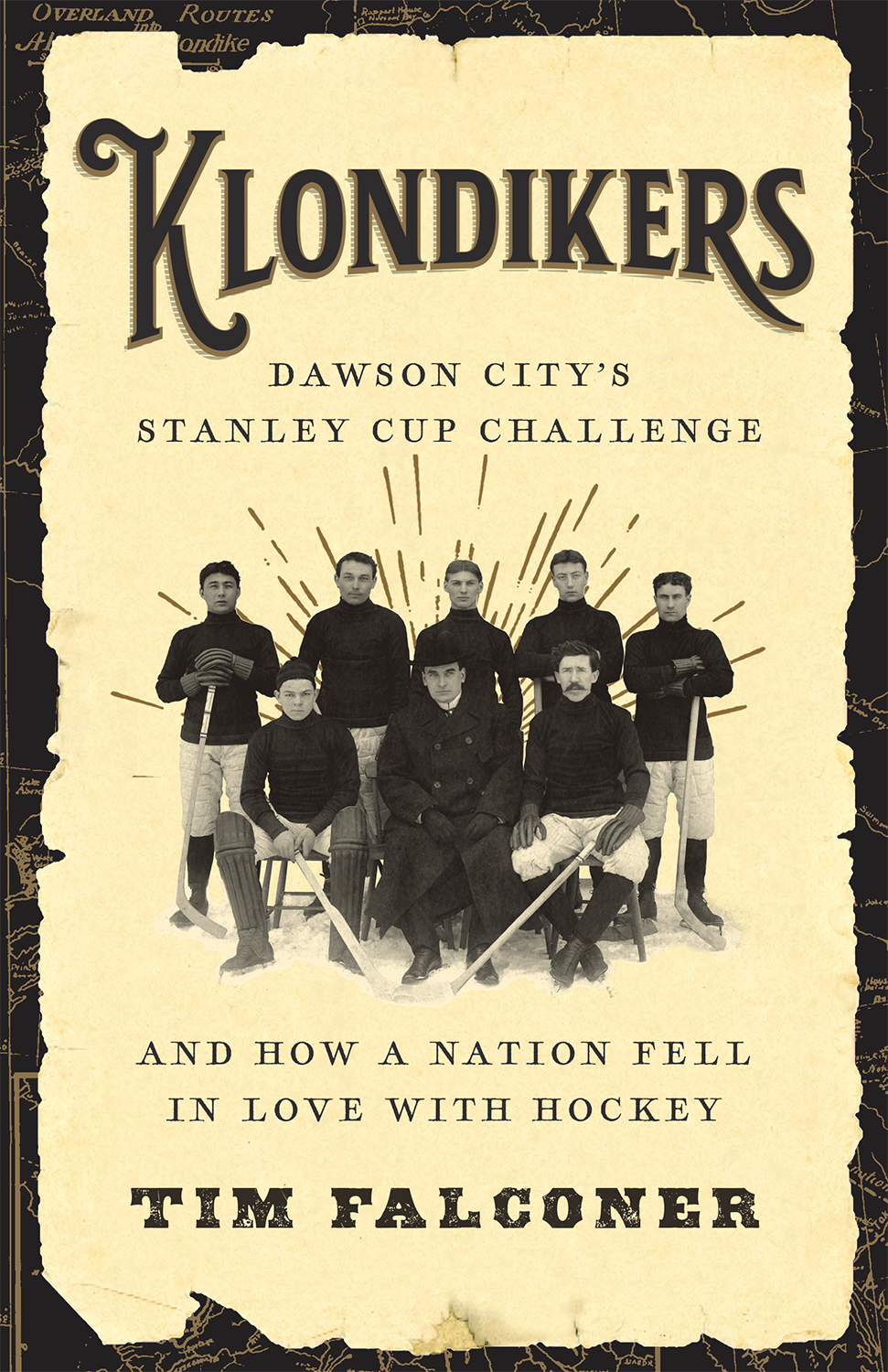

They believed the hardship was worth it. Since 1893, the reward for being Canadas best amateur team was the Dominion Hockey Challenge Cup, a silver bowl donated by Lord Stanley of Preston, the governor general at the time. Known from the beginning as the Stanley Cup, it quickly became the most prestigious trophy in the land. While the trustees wouldnt allow just any team to contend for the honour, they did approve a challenge from Dawson Citys all-stars. To win the Cup, the Yukoners would have to defeat the formidable Ottawa Hockey Cluba team known in lore as the Silver Sevenand the sports original superstar, One-Eyed Frank McGee. Few hockey people considered the Klondikers a serious threat. The team was from a small subarctic town and no squad from west of Brandon had yet challenged for the Cup, let alone won it. When accepting the challenge, Ottawa insisted the Dawson team not play any exhibition matches en route. Rather than an attempt to ensure their opponents would arrive unprepared, this was to avoid any losses to weaker teams that might discourage ticket sales for the Cup series.

The original plan, as set out by Joe Boyle, the brash businessman managing the tour, was for a layover in Winnipeg to do some training. But the team was so far behind schedule, that was no longer an option. With just a two-hour stop before continuing on to Ottawa, the players didnt have enough time to do much more than stretch their legs and assure reporters their challenge was no joke. Despite the teams lack of star power, the cross-country trek charmed Canadians. Though the codified version of the sport was only three decades old, passion for hockey had swept the nation since Lord Stanley had donated the Cup and was only intensifying. But there was more to the enthusiasm for the underdogs from the Yukon than a love of the game. The Klondike Gold Rush was over, but people continued to romanticize the North. And the long journey from that faraway land to the nations capital fit into that mystique. All along the route, fans had cheered the Yukon team. And it was no different in the home of the champions, where the Citizen reported, The matches are creating the greatest interest of any Stanley Cup contests yet played in Ottawa.

At a quarter to five on January 11, 1905, three and a half weeks after leaving Dawson City, the hockey players stepped off the train and onto the platform at Ottawas Central Station, where a large and appreciative crowd gave them a right hearty reception. Bob Shillington, the manager of the Cup-holding team, and other club executives led the players away to the Russell House. A throng overflowed the hotels rotunda in hopes of catching a glimpse of the exotic visitors. But the cordial welcome didnt mean the hosts were about to grant Dawsons request for a one-week postponement before starting the best-of-three series. Meanwhile, the challengers denied a newspaper report that theyd default the series opener and focus on the second and third matches rather than play unprepared. The first game would go ahead as scheduled, with Earl Grey, the new governor general, facing the puck at 8:30 p.m. on Friday the 13th. After nearly a month on the road, the exhausted and far-from-game-shape Klondikers would take on the reigning Stanley Cup champions before a sellout crowd of 2,500 fans at Deys Rink in just over forty-eight hours.

Part One

One :

It looks like any other trophy, I suppose

Still just twenty years old, the boyishly handsome and clean-cut Weldon Champness Young was already a veteran star with the Ottawa Hockey Club when he went to the Russell House for a formal banquet. The March 1892 evening, hosted by the Ottawa Amateur Athletic Club, was to celebrate his teams season. So it was fitting that when Weldy, as everyone called him, and the other guests sat down at the elegant place settings, they found menu cards that told two tales. One side, as usual, set out the fine fare the hotel would serve that Friday night. The other showed the names of the OHC players and an account of another impressive season. In ten matches that winter, the squad had won nine times, scoring fifty-three goals and allowing only nineteen. This was the record, according to the Evening Journal, of a genuine amateur team playing for pure love of sport and treating all comers as they wished to be treated themselves. More than seventy-five sportsmen had gathered in the dining room to honour the players, but by the end of the night theyd have something else to cheer about.

Located a short walk from Parliament Hill, on the southeast corner of Sparks and Elgin streets, the five-storey Russell House was the citys finest hotel. Popular with Ottawas high society, who enjoyed the luxurious public rooms and excellent food, the establishment was the obvious choice for a banquet that attracted many distinguished local gentlemen, as well as guests from Montreal and Toronto, and featured music from the Governor Generals Foot Guards band. Women joined the festivities around 9:30 p.m., taking seats in a wing of the dining room, and the hotel staff served coffee and ices. At ten oclock, OAAC president J. W. McRae began the evenings formal proceedings. A lengthy round of toasts was a regular part of such gatherings and, by tradition, the host always led off with one to the Queen. After McRae had done so, Philip Dansken Ross, the Evening Journal publisher and OAAC past president, drew cheers for his toast to the health of the governor general, including complimentary remarks about the Englishmans staunch support of sports, especially hockey.

In 1888, an aging Queen Victoria had tapped Frederick Arthur Stanley, the forty-seven-year-old son of a former Tory prime minister, to be her Canadian representative. After serving two decades in Parliament, where he held several portfolios, including Secretary of State for the Colonies, Baron Stanley of Preston entered the House of Lords in 1886. Yet his career always seemed overshadowed by the political accomplishments of his father and brother. The viceregal position in Ottawa, not exactly the most glamorous, or warmest, city in the British Empire, sure wasnt about to change that. In fact, it sounded more like a retirement posting. Initially, he declined the Queens offer, but Lord Salisbury, his prime minister, talked him into becoming the Dominion of Canadas sixth governor general.