Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

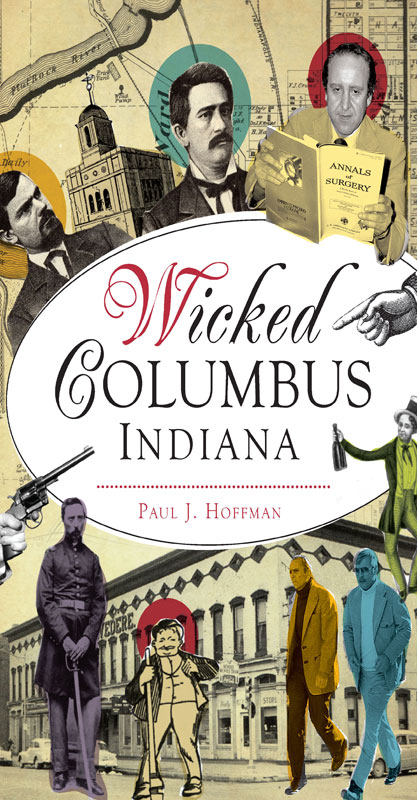

Copyright 2017 by Paul J. Hoffman

All rights reserved

First published 2017

e-book edition 2017

ISBN 978.1.43966.132.1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017931814

print edition ISBN 978.1.62585.871.9

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I extend my sincere appreciation to the Republic newspaper and its owner, AIM Media Indiana, for allowing me access to all of their historical documents. Id also like to thank Cody Anspaugh, museum assistant at the Bartholomew County Historical Society, and the staff of the Bartholomew County Public Library for help securing photos and information. Thank you to the best copy editor in these parts, Katharine Smith. And finally, Id like to thank my wife, Kimberly S. Hoffman, for her support and for allowing me to become somewhat of a hermit for several months.

INTRODUCTION

Situated where the Flat Rock and Driftwood Rivers merge to become the East Fork of the White River in south central Indiana, the city of Columbus has a long, proud history.

Known nationwide as one of the smaller cities to boast a vast array of modern architecture, the county seat of Bartholomew County is called home by roughly forty-six thousand residents today. Columbus sits approximately forty miles south of Indianapolis; eighty miles north of Louisville, Kentucky; and ninety miles west of Cincinnati, Ohio.

The high number of notable public buildings and public art in the Columbus area, designed by such well-known and respected individuals as Eero Saarinen, I.M. Pei, Robert Venturi, Csar Pelli, Harry Weese and Richard Meier, have led to Columbus earning the nickname Athens of the Prairie.

Two hundred years ago, however, this area was definitely no prairie; it was teeming with lush, green forests, swamps and Delaware Indians.

In its infancy, the locale wasnt even called Columbus. It was called Tiptona after General John Tipton, a famed Indian fighter and prominent landowner who was one of two men to donate thirty acres for the fledgling town; pioneer Luke Bonesteel was the other. Five weeks after being platted, however, the name of the town was changed to Columbus.

Nobody seems to know for sure why Tiptona was scrapped for Columbus. Historians have speculated that Tipton, a Democrat, had an argument with local Whigs, although evidence of that is scarce. It is possible that the new name was used so that pioneers concerned about poor health would associate this community with the hardy explorer of the New World and/or the well-established Columbus, Ohio.

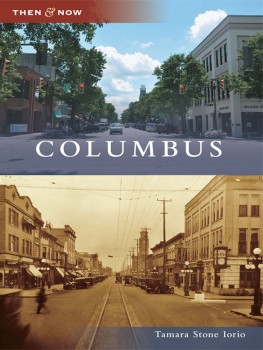

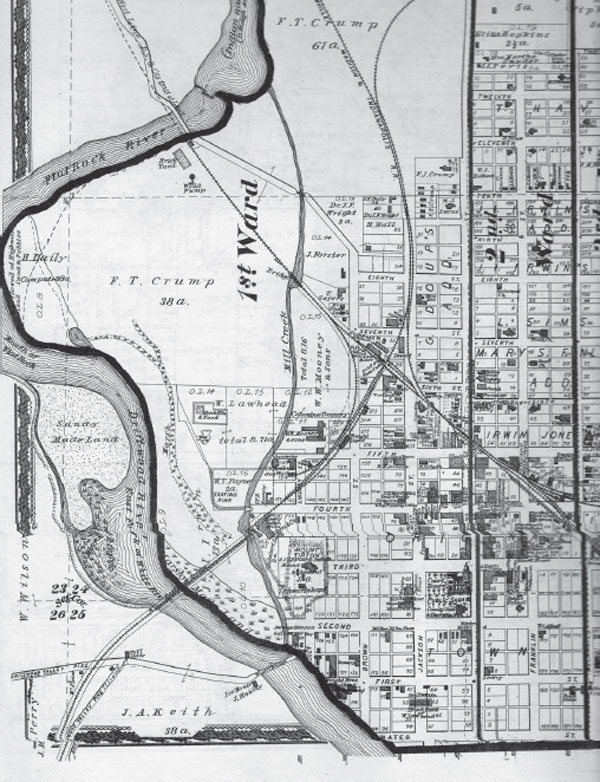

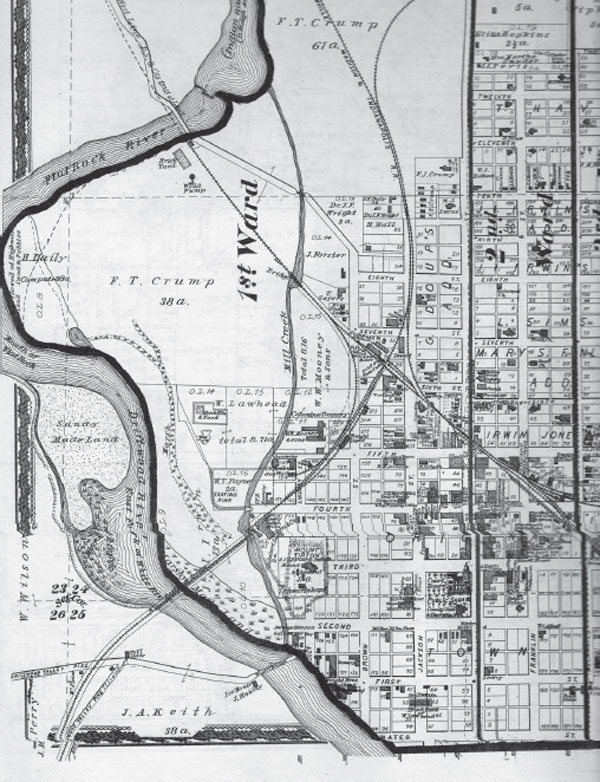

Columbus map, 1879. Illustrated Historical Atlas of Bartholomew County, Indiana.

In 1816, Indiana advanced from a territory to a state, the nineteenth to join the union. Three years later, Bartholomew County was carved out of part of the original Delaware County. Columbus was platted in 1821, becoming the seat of county government immediately. It was incorporated as a town in 1837 and as a city in 1864; residents elected Smith Jones as their first mayor.

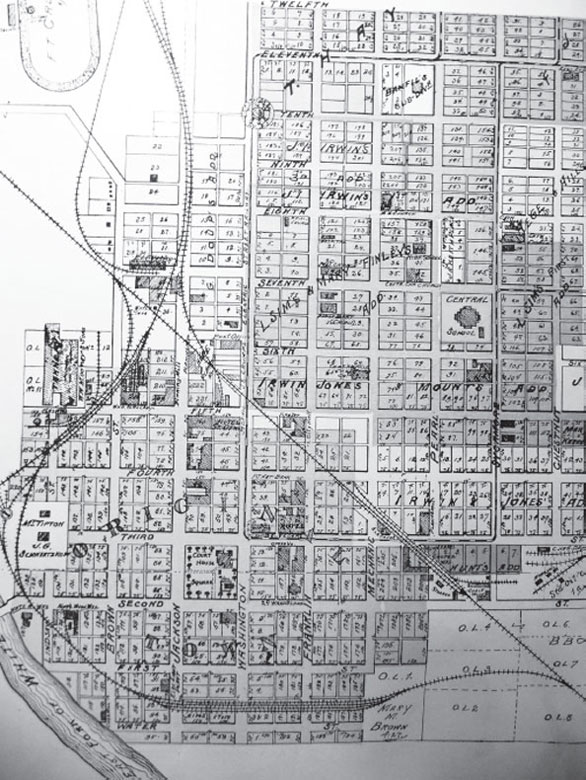

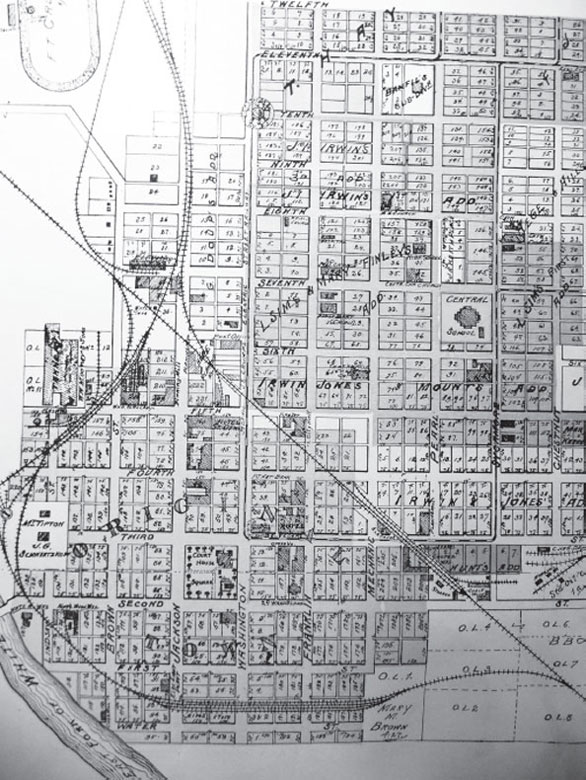

Columbus map, 1900. Descriptive Atlas of Bartholomew County, Indiana.

Prosperity came to town with the introduction of the railroads in 1844, when the line being laid from Madison to Indianapolis made it to Columbus. That line was followed by connecting routes to the Indiana cities of Jeffersonville, Shelbyville, Hope and Greensburg, as well as to St. Louis and Chicago.

Business boomed during the Civil War, as a local bakery supplied the Union army. Banks were established, which brought stability. Between 1850 and 1900, Columbuss population increased seven-fold, rising from just over one thousand to more than eight thousand.

World War II brought another surge of prosperity, as small, homeowned businesses fulfilled government contracts, and manufacturers such as Cummins, Arvin Industries and Hamilton Cosco all grew during this era. The number of Columbus residents nearly doubled between 1940 and 1960, from 11,738 to 20,778. And the population has more than doubled since then.

Throughout its history, Columbus has maintained a reputation as a safe place to raise a family with a decent standard of living, good schools and wholesome entertainment options.

However, all cities (even ones known as the Athens of anywhere) have had their ups and downs, their unsavory citizens and challenging issuesor just their share of plain old bad luck. The tales told in this book should not be construed as a condemnation of the city as it is today in any way, shape or form. All of the events described in this book are more than thirty-five years old, and many of them are more than a century past.

Many other cities across the country have suffered similar, and even more severe, consequences due to their bad times and people. To their credit, the residents and elected officials of Columbus have more often than not found a way to solve their problems.

With that in mind, I hope you enjoy reading about the unsavory, the unlucky, the challenging and the wicked who have added intrigue to Columbus.

Thank you.

FEUDING MAYOR, EDITOR ENGAGE IN

STREET FIGHT

Among their duties, reporters and editors are tasked to hold public officials accountable for their statements and actions. And the government is not allowed to infringe on the freedom of the press, a right set out explicitly by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

When both sides of this equation do their jobs properly, government officials and members of the media form a sort of mutual dependence society. Officials need the newspapers, television and radio stations to disseminate information to their constituents. The media need those officials to provide all the information necessary to tell the public what it needs to know.

When either media members or those appointed or elected to run a particular governing agency fail to do their jobs properly, this system can sputter and perhaps break down, as the parties lose trust or respect for each other. Rarely, though, does the relationship turn so ugly that a government official and a journalist end up in a knock-down, drag-out fistfight.

Columbus saw one of those rare battles on a cold December day in 1877, when the youngest mayor in Indiana and the oldest newspaper editor in the state engaged in quite a battle on a city street.

Looking at biographies of the two combatants today, it might be difficult to understand how two well-respected gentlemen could have ended up in a tussle that left one of them with two black eyes and the other missing some of his whiskers and part of a finger. Mayor George W. Cooper of Columbus and Isaac M. Brown, editor of the

Next page