Acknowledgments

Sections of this work have been published in Snow Country Magazine, Travel and Leisure, Boise Magazine, Boise Weekly, and The Idaho Mountain Express, and anthologized in the volumes Written on Water, Where the Morning Lights Still Blue, and Father Nature. I wish to thank Chris Farnsworth, Alan Minskoff, Pam Morris, and Kathleen Ring for their editing, encouragement and friendship, and Erik Henriksen for a perceptive and honest reading. Jim Hepworths faith in my writing has kept me a writer when I might have tried my hand at creative accounting instead, and Dan Frank, as an editor and wonderfully intuitive reader, has shown me deep and quiet places in my stories where other stories lay hidden. Without the help of these people, and without the bright presence of Julie Rember in my life, this book would not have been written.

In the early spring of 1961 a friend and I were making a snow fort on Warm Springs Avenue in Ketchum, Idaho, when Ernest Hemingway walked up and began staring at us.

After a few minutes he said, What are you doing?

We replied that we were making a snow fort.

A little while after that he said, Hello, boys.

We said hello.

What are you doing? he said again. We had already answered that question. He stared at us in silence for a while, and then hobbled on down the road.

It was the post-shock-therapy Hemingway. He was gaunt and crazed and looked a hundred years old. If he had been a phoenix, he would have been inflames.

My friends father ran a welding shop, and the day Hemingway killed himself Mary Hemingway brought the shotgun into the shop and had it cut into little pieces with an electric hacksaw. She left with the pieces in a canvas bag.

I knew then that whatever else I might become, I would never become a writer.

A long time later I came to Hemingway as a writer, and my dealings with him can be summed up this way: every time Im working on a story and I think Im discovering a new technique or finessing an old one, I find that he did the same thing better long ago.

But I hope my intent is different. Hemingways suicide has always stayed with me. I know that his work and his death are intertwined, but its still a shock to pick up The Sun Also Rises and see its hero, the imperfectly constructed Jake Barnes, end that book alone, impotent, defiant, in despair, and in love with death. In the end, Hemingway bagged the biggest, most dangerous story of them all as it charged at him from out of the concrete and Formica surfaces of his house in Ketchum.

The stories in this book are fragments of my life and my memory and my imagination. Ive tried to be kind to their truths, even when those truths arent kind to me. Ive also tried to keep my own perceptions from becoming the tools of the kill.

All our stories rest on other, older stories, and if were careful, and if were kind, and if we pay deep attention to memory and its tricks, we can bring forth our stories and keep those older stories intact. Its a way of saving our lives.

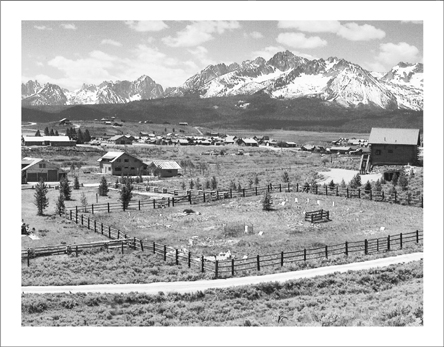

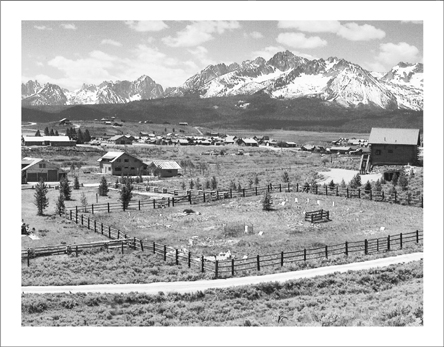

I N 1987 I cashed out of the ski resort of Sun Valley, Idaho, and went fifty miles north to my familys place in Sawtooth Valley to build a house. I did so out of a deep homing instinctthe same forty acres that had sustained our tiny herd of horses every summer for thirty-five years had sustained, for me, a vision of a place where I belonged in the world, where I could get up in the morning, step out the door, and catch dinner from the Salmon River, or simply step out to watch the sunrise light the Sawtooths above their dark foothills. And then, depending on my horoscope in a week-old Idaho Statesman or the shape of the mornings clouds, I could fix the fences, cut firewood, change the water on the pasture, plant trees, or just fish some more.

It was a vision of a life, I think now, that came from memories of our horses, brought from winter pasture every June, whinnying and bucking around the fence lines, biting into the spring grass, running full-gallop through the shallow water on flooded river islands, home at last. Such memories become metaphors, and in early middle age, such metaphors become calls to action.

So when I found myself in the unexpected financial condition of being able to return home, I did. The house was begun in September 1988 and, owing to good weather all through that fall, was finished in February 1989.

That March I sat at my desk, warm and comfortable, the nearby cold of the Sawtooth Valley spring held harmless by thermopane windows and six inches of fiberglass. If I looked up from my monitor, I could see the cold stone towers of Mount Heyburn, their ragged edges smoothed by thick drifts of snow. The willows in the river bottom were skeletal and frosted, but every bit as beautiful as they would be that July, when the horses would hide in them to escape the flies and the heat. The snow on the valley floor held my weight in the mornings, and at least once a day I went out to wander the fence lines, or sat on the melted-off riverbank to watch the flyovers of returning geese, or skied the hill behind the house, or ran to the mailbox when I heard the mailman accelerate toward his next target, my neighbors mailbox a mile up Highway 75. Home at last.