SCOTT,

CHAUCER,

AND

MEDIEVAL

ROMANCE

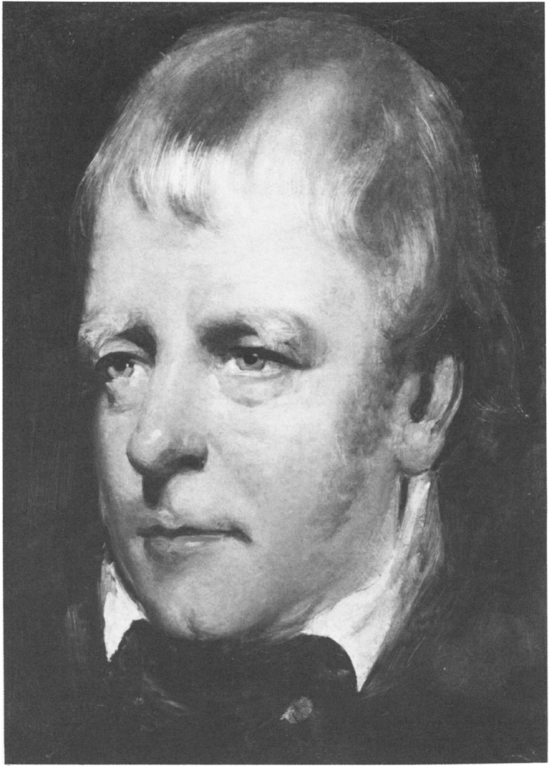

Sir Walter Scott, from a portrait by John Watson

(later Sir John Watson Gordon). Courtesy of the

Scottish National Portrait Gallery.

SCOTT,

CHAUCER,

AND

MEDIEVAL

ROMANCE

A Study in Sir Walter Scotts

Indebtedness to the Literature

of the Middle Ages

JEROME MITCHELL

Copyright 1987 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth

serving Bellarmine College, Berea College, Centre

College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Club, Georgetown College, Kentucky

Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40506-0024

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mitchell, Jerome.

Scott, Chaucer, and medieval romance.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. Scott, Walter, Sir, 1771-1832KnowledgeLiterature. 2. Scott, Walter, Sir, 1771-1832Sources. 3. Chaucer, Geoffrey, d. 1400InfluenceScott. 4. RomancesHistory and criticism. 5. Middle Ages in literature. 6. Medievalism in literature. 7. Literature, MedievalHistory and critcism.

I. Title.

PR5343.L56M58 1987 828.709 87-8294

ISBN 0-8131-1609-0

For

my mother

MARIE DICK MITCHELL

and my brother

JOHN LEE MITCHELL

and in memory of my father

EMERSON LEE MITCHELL

CONTENTS

PREFACE

THIS BOOK is a study of Sir Walter Scotts indebtedness to Chaucer and to medieval romance, especially the Middle English romances, for story-patterns, motifs, character types, style and structure, and detail of one sort or another. In the first of eight chapters I establish as best I can the extent of Scotts knowledge of medieval literature, showing which romances he knew (and in which editions), which romances he knew of and had read in, and which ones he did not know. In the second chapter I discuss his poetry, especially the long narrative poems, in relation to Chaucer and medieval romance. Chapters 3 through 6 deal mainly with the Waverley Novels: the early novels, 1814-16; novels of the broken years, 1817-19; novels of the high-noon period, 1820-25; and novels of the dark days and servitude, 1826-32my phraseology coming from John Buchans beautifully written biography, Sir Walter Scott (London: Cassell, 1932). In these chapters I go through the novels one by one, showing what specifically Scott has drawn from Chaucer and medieval romance and how he has used it. In some of the novels the borrowing is superficial; in others it runs deep and is essential to what Scott is doing. Matters of style and structure relevant to the poems are discussed in the second chapter; the seventh is devoted to style and structure in the novels. In the last chapter I try to explain how Scotts reliance on Chaucer and medieval romance enhances and deepens his poems and novels and why it works so effectively.

John Gibson Lockhart, his son-in-law and biographer, once said about Scotts Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border: No person who has not gone through its volumes for the express purpose of comparing their contents with his great original works, can have formed a conception of the endless variety of incidents and images now expanded and emblazoned by his mature art, of which the first hints may be found either in the text of those primitive ballads, or in the notes, which the happy rambles of his youth had gathered together for their illustration. Much the same can be said about Scott and medieval literature. I believe that medieval romance is the single most important literary source for the Waverley Novels, even more pervasive than Shakespeare (whose influence on Scott was great and profound), and that an understanding of Scotts debt to it is the key to an understanding of his immense appeal. Let me say too that I fully realize the danger inherent in a study of this sort. When one source area is put under a magnifying glass, it inevitably gets blown up out of proportion. As great as the influence of medieval literature is, it does not overshadow all other influences, for Scotts reading was vast and omnivorous. Here and there I have cited other possible sources.

While it has long been known that Scott knew medieval romance, other studies have been concerned with his medievalism in general rather than with specific indebtedness to specific romances. The present study deals, as much as possible, in specifics within the boundaries I have set. Some limitations in scope have been necessary and inevitable. I have not said very much about Scott and Italian romance, and for this subject I refer the reader to R.D.S. Jacks chapter on The Novel and Scott in his pioneering book, The Italian Influence on Scottish Literature (Edinburgh: Edinburgh Univ. Press, 1972). I have also not said much about Scotts debt to Old Norse; for this material the reader may consult John M. Simpsons Scott and Old Norse Literature, included in the Scott Bicentenary Essays, edited by Alan Bell (Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press, 1973). I have given very short shrift to chronicles and to long works that hover between romance and chronicle, like Barbours Bruce. As for ballads, I have tried to limit myself to those that share motifs with romances that Scott knew and to those that are later versions of romances. (The farther our researches are extended, Scott once wrote, the more we shall see ground to believe, that the romantic ballads of later times are, for the most part, abridgments of the ancient metrical romances, narrated in a smoother stanza and more modern language.) Despite these and other limitations, a wealth of material is here, and the scope of the present study is very large.

I would like to express special thanks to the helpful and friendly staff of the National Library of Scotland, in Edinburgh, where I did the major part of my research. Most of the material I needed was thereand the library is close to where the house once stood, at the top of Guthrie Street, in which Walter Scott was born; it is only a short distance from George Square and the house, still standing, in which he lived as a boy and young man; it is only a stones throw from the site of the old Tolbooth, long since demolished and removed, where Effie Deans was imprisoned for having allegedly murdered her newborn child; it is at the top of a steep street (Victoria Street and West Bow) leading into the Grassmarket, where Captain John Porteous was lynched by determined avengers before a mob of onlookers; it is a twenty-five-minute walk from the Salisbury Crags, where one awesome night Jeanie Deans met with the seducer of her sister and where on pleasant days young Walter Scott and his friend John Irving used to go to read old romances together and to compose new ones for each others amusement. I must also thank the library staff at the University of Bonn, where I read the German dissertations that I cite in this book; many of these had to be ordered on interlibrary loan, sometimes from East Germany. I am also indebted to many individuals for help, especially James C. Corson, Kurt Gamerschlag, George O. Marshall, Jr., Patricia and Jean Maxwell-Scott, Coleman O. Parsons, Charles I. Patterson, Jr., and Donald E. Sultana. Without their advice this book would have been the poorer, and without their encouragement it might never have been. I hasten to add that all faults and shortcomings are entirely my own.