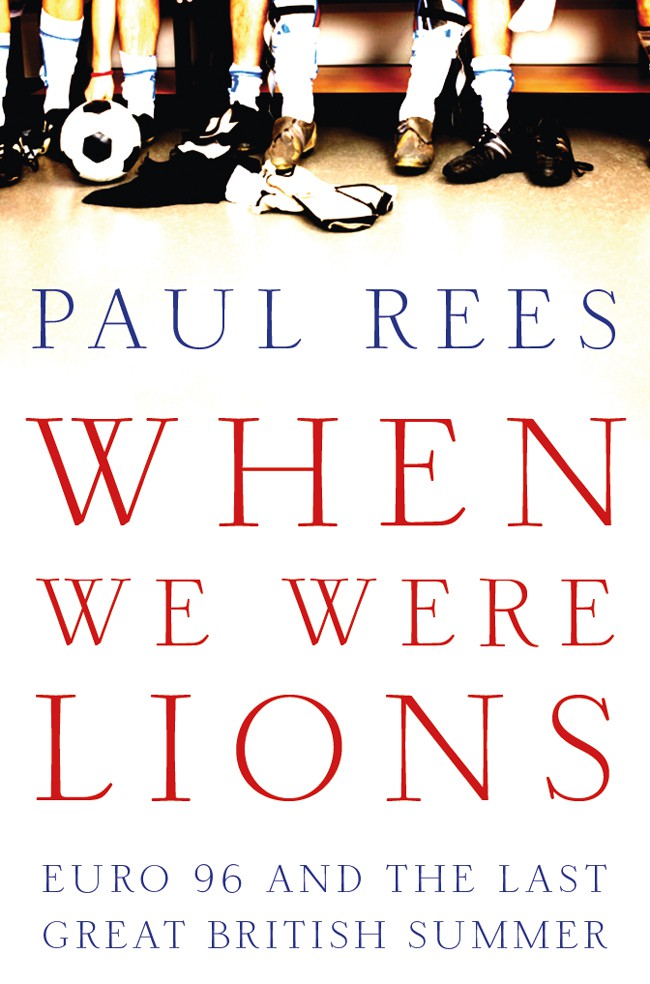

A s darkness ran to dawn on the morning of Thursday, 27 June 1996, Paul Gascoigne could be heard sobbing himself to sleep. During the previous three weeks a more uproarious sound would have been booming out from his room at Burnham Beeches Hotel, a grandiose whitewashed pile near Slough where the England football team were billeted. On any given morning or afternoon, Gazza would crank up his portable CD player, throw open the door and windows and let the adopted anthem of Englands Euro 96 campaign reverberate down the corridors, across the landscaped lawns and out to the supporters thronging the leafy approaches to the hotel. The crowds would then pick up the songs triumphal chant and send it rolling back to Gascoigne with gusto. Its coming home, its coming home, its coming, footballs coming home, they sang, their voices raised in exultation.

To be sure, the summer of 1996 was an extraordinary time to be in Britain and to be British, and most especially English. It was the summit of a halcyon period in thecountrys modern history, both socially and culturally. The cresting of a boundless mood of optimism and patriotism that had bubbled up during the preceding two years and swelled through sport, music, art, fashion and even politics. The mid-1990s were when Tony Blair and New Labour emerged, Oasis, Blur and Britpop boomed, Kate Moss was turned into a fashion icon and Trainspotting revived the British film industry with an electrified jolt. Through that sun-baked month of June, Englishmen strove to win the Wimbledon tennis championship, the Formula One world drivers title and The Open golf tournament. There, though, at the very centre of things were Euro 96, the Three Lions and Gazza, rallying points for all Englands hopes and dreams.

England started the tournament slowly but gained momentum and swept the country along with them. As Euro 96 unfolded, thirty years since the national football team had won its last and only major honour, it seemed increasingly as if the side moulded by head coach Terry Venables, and blessed with Gascoignes magical touch, was going to repeat the feat. The euphoric scenes that accompanied Venabless men to, during and from each of their games were now etched in the national consciousness, indelible and definitive of the era. If that euphoria could be distilled into a single image, it would be of the old Wembley Stadium, its crumbling terraces packed and turned to a sea of red and white St Georges flags. This was England that June, revelling in the moment when thrilling and powerful forces collided, on the cusp of promised glory.

At the witching hour on that Thursday, however, the grounds of Burnham Beeches, like the country as a whole, were silent and still. Towards midnight the England team bus had rumbled up the hotels tree-lined avenue, returning them to rural Berkshire from the hustle, bustle and noise of Wembley. The hotel staff and a small retinue of locals lined up on the driveway to greet them. Gascoigne, his team-mates and Venables were cheered into the lobby. They smiled back dutifully, but their faces were frozen in a kind of disbelieving, dead-eyed shock. Among them were the stoical Alan Shearer, the tournaments top goalscorer, and his strike partner, Teddy Sheringham; the two full-backs, young Gary Neville from Manchester United and the veteran Stuart Pearce, who had informed the coaching staff and his team-mates during the journey that he meant to retire from playing for England; the captain, Tony Adams, who looked as if he would run through a brick wall; Paul Ince, Gascoignes partner in midfield and such a swaggering presence he christened himself The Guvnor; and the Liverpool duo, Steve McManaman and Robbie Fowler, whose antics had amused and irked Venables in equal measure.

Each one of them had anticipated coming back victorious, triumphant, with one more spell-binding night in North London still ahead of them. On the evening of 30 June they meant to lay to rest thirty years of hurt by winning the Euro 96 final and securing for themselves the sporting immortality enjoyed by Sir Alf Ramsey and his boys of 66. That much had seemed to thempre-destined ever since their second game of the tournament when Gascoigne lit the fuse with a breath-taking act of impudence and sheer brilliance against Englands oldest football rivals, Scotland.

Saturday, 15 June, twenty-five minutes to five oclock on a roasting summers afternoon at Wembley. At that precise moment, Gascoigne collected a hopeful forward punt from Darren Anderton. In a single, fluid movement, running between two Scottish defenders on the edge of the opposition penalty area, he lifted it over their heads and met it on the volley. The shot speared into the Scottish net, winning the game for England and sending into raptures the thousands of English supporters in the stadium as well as millions more watching on television at home and in countless pubs and clubs across the country. After a stuttering start, it was Gascoignes intervention that sparked England and the tournament into life. It also restored Gascoigne to his exalted position as the finest English player of his generation and a national treasure.

Going into Euro 96, Gascoigne had been written off, his mental and physical fitness in serious doubt and his powers perceived to be waning. On the eve of the tournament, notably after the team returned from a disastrous warm-up trip to China and Hong Kong, he was singled out, demonised in the press and faced a growing movement to have him kicked out of the squad. The prodigiously talented boy-man who had first enraptured the nation by shedding tears as England crashed out on penalties to West Germany in the semi-final of the Italia 90 WorldCup appeared now, at just twenty-nine, to be broken and spent. A fallen hero wrecked by his own ill-discipline on and off the pitch and beset by demons. The awesomeness of his goal against the Scots reversed that notion at a single, dazzling stroke. It was as if he had somehow been able to roll back time and recapture the essence of himself. From that point on the England team moved to Gascoignes beat: a dextrous, conjuring rhythm. His displays at Euro 96 returned him to the pinnacle of his sport.

Gazza was especially influential in Englands next match against the Dutch, one of the pre-tournament favourites and among the powerhouses of world football. Revelling in having the ball at his feet, and using it with the precision of a surgeons scalpel, Gascoigne was the teams fulcrum, the pivot around which they were able to confront and crush the Dutch at their own cultured game. Collectively, it was a performance for the ages, the highest point of Venabless tenure. That had begun after England failed to qualify for the finals of the 1994 World Cup and were left mired in the doldrums of international football. But in much less than three years they had reached this giddy point. Cavalier and canny, Venables had restored self-belief and a sense of pride to English football, building a team of equal parts strength and skill, with leaders such as Adams, Pearce, Ince and Shearer and artisans like Gascoigne, Sheringham, Anderton and McManaman.

England advanced to a semi-final against the Germans. That meeting took place on the grey, humid evening of 26 June and proved to be a gripping battle of wills. Itpitted the two best teams in the tournament, its heavyweights, against each other and they stood toe-to-toe, trading blows across the lush expanse of the Wembley pitch. England were looking to avenge their cruel defeat in Turin. Their opponents were seeking to exorcise the ghost of 1966 when Ramseys team put a strong West German side to the sword. Before the encounter six years earlier, Englands then-manager, Bobby Robson, had told a callow Gascoigne that he would be facing the worlds best midfielder, the Germans imperious schemer Lothar Matthas. No, Bobby, Gascoigne shot back, youre wrong he is. Now, Gascoigne was once again as confident and bullish, assured of his status as the games pre-eminent playmaker. He strutted through the battle, Englands lightning rod, the channel through which the ebb and flow of the match was set and controlled. He was so sure of his moment and looked certain to seize it.