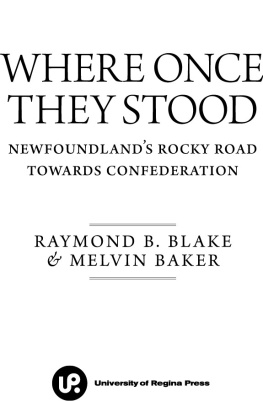

The

DANGER

TREE

MEMORY, WAR, AND THE SEARCH

FOR A FAMILYS PAST

DAVID MACFARLANE

To my parents

LISA MOORE

An Introduction

O n the paternal side of David Macfarlanes family tree there are deep silences. There is little conversation at the dinner table. In fact, there are full-blown marathons of speechlessness. Theres the staid, unboisterous decorum of a family with roots in Hamilton, Ontario.

But Macfarlanes profoundly touching and stylistically brilliant memoir is not about his fathers side of the family. Nor is it a history of Hamilton, where Macfarlane grew up and about which he wrote many essays when he was a young schoolboy.

By the time Macfarlane outgrew these homework assignments, he had already inherited something of his fathers familys silences and had become a typically sullen adolescent. He saw Hamilton as an unexceptional place, one with which he was quite comfortable.

What follows is a potent antidote to all that silence, although Macfarlanes layering of memory may owe something to his fathers practice, as an optometrist, of sliding one lens over another with delicate little clicks, allowing him to tinker with the patients depth of field and ability to focus, while asking repeatedly: Better or worse? Better or worse?

Macfarlane similarly shifts the readers focus and depth of field from Newfoundlands very deep past to a past not so long ago, clicking back and forth, so that what results is a seamless and sensuous tumult of stories, by turns factual and fanciful, honest, and burning with feeling. He speaks with the passion of a dedicated archivist. He is part ethnographer, part historian, part novelist, with a novelists eye for character and illuminating detail.

As a young boy, David recognizes his parents marriage may be some kind of historical accident or reckless experimentnot unlike Newfoundlands union with Canada, the reader might conclude.

From there Macfarlane begins to dig around the roots of his own danger tree, a family trove of stories that seem as vivid, astonishing, and magical as anything by Gabriel Garcia Mrquez or Salman Rushdie.

The tale, for instance, of Macfarlanes motheran infant in a little box tied to the front of a dog sled, drawn across a frozen river until the lead dog halts in fear, just before the ice cracks like a china plate, threatening to drown Davids mother, his maternal grandparents, and the possibility of a future David, all in one big gulpis a heart-juddering myth of origin.

Macfarlanes kin, on his mothers side, are the Goodyears. They are a prominent Newfoundland family, originally from the outport of Ladle Cove, who moved to the interior of the island when a paper mill in Grand Falls promised great opportunity for Newfoundlanders brave enough to pull up stakes and move away from the coast.

The Goodyears, innovators of industry, were responsible for building the road from Gander Bay around the loop to Gambo. This gargantuan enterprise, akin, perhaps, to building the Suez Canal, required traversing a bog that swallowed tractors whole, and the sinking of a half-million fifteen-foot logs that served as a foundation for the road.

When asked by a local newspaper how long the road would last, Macfarlanes great-uncle Roland responded: The answer is, forever.

Roland worked endlessly on a rambling history of either the Goodyear family, or Newfoundland, or the world, and Macfarlane picks up where his great-uncle left offwriting with wit, authority, and succinct, limpid prose.

He reaches back through forever, through time and memory, hearsay and letters, family stories and photographs, to set a historical foundation as solid as the petrified logs on which the road was built. He gently excavates the roots of his own family history, a birthright of storytelling, a landmark in the inchoate universe of interior Newfoundland, and an inheritance of unfettered imagination.

Macfarlanes maternal family evolves as a multifaceted cast of characters who are eccentric, enterprising, sometimes ornery, often very funny, bold, and uncompromising. They are larger than life. His great-aunt Kate, for example, was an unsentimental woman who did not suffer fools, but who was sometimes given to sudden bursts of tears. Tears that would come out of nowhere, interrupting stories at the family dinner table.

This is a story of the nation of Newfoundland, wild schemes and pirate tales, invention and loss, and the tremendous cost of war. Macfarlanes relatives are brave and willing to risk all. They are dreamers and, best of all for the reader, robust storytellers.

Macfarlane pulls focus, and the wide world touches down in Grand Falls. Lord Alfred Harmsworth Northcliffe builds the paper mill to feed the newspapers of Europe during the war. The Goodyears profit from their move to the interior, and their profits wane; they are rich, or they go bust. They are in constant contact with the irascible and all-controlling former premier Joey Smallwood, whom, Macfarlane suggests, must be petitioned for construction contracts with gifts: flowers, live chickens, and birthday cakes.

Macfarlane folds together all of Newfoundlands founding myths: Marconis first wireless message, the horror of Beaumont Hamel, the great sealing disaster of 1914, the transatlantic flight of Alcock and Brown, to name a few. This casting back unfurls the fortunes and misfortunes of Newfoundland as a nation, its role on the international stage and in the two World Wars, its relations with the British Empire, and, finally, its confederation with Canada.

Perhaps the most devastating imagery of this memoir appears in the description of how the bullet of a Mauser 98, the weapon used by German snipers during the First World War, passes through the human brain.

Here Macfarlane slows time, or deepens it, so that a third of a second becomes a long, dark tunnel, the barrel of a gun, and the 300 yards of No Mans Land through which a bullet must travel. The description of the trajectory, precisely rendered, creates a paradoxical effect: the travelling bullet seems to decelerate, slows to the rhythm of Macfarlanes sentences, or to the time it takes the reader to comprehend the speed, like the eternity of nothingness that waits on the other side of the bullets impact.

Skin, then bone, then brain slowed the bullets passage, but as the bullets velocity was reduced, it transferred its kinetic energy to the cranium. This commotion radiated out from the bullet like a shock-wave, and blasted the brain to unconsciousness before the sensation of pain had reached it from the point of entry.

I discovered myself vulnerable to the same affliction of sudden tears that Davids great-aunt Kate suffered while I was reading The Danger Tree. I re-read this book, most recently, on a beach in Goa, India; in Pearson International Airport; in Broad Cove, Conception Bay, Newfoundland; and at Fixed Cafe in downtown St. Johns. I often found myself looking up from Macfarlanes memoir to see my immediate surroundings blurred, my face wet.

Macfarlane shows the absurdity of the First World War without diminishing the sacrifice of the young men who left Newfoundland to fight in the battlefields of Europe. He recognizes the bravery required to face a horrendous, unnecessary death. While the soldiers who were mowed down near Beaumont Hamel are treated like heroes in Macfarlanes account, he is, at the same time, emphatic about the senselessness of the war.