For E, always

Contents

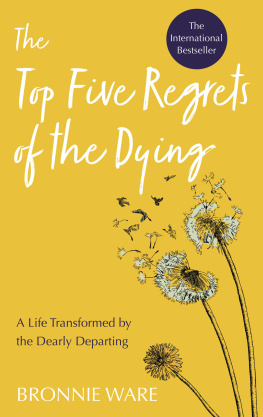

Some of the regrets youre about to read are very clear and concise. Some are not. Some are quieter, and less assuming. And some, given the circumstances they were borne out of, may not be what youd expect them to be.

I had two caveats when going out to find people to interview for this book: that they were over the age of 70, or that they were living with a life-limiting illness. My aim was to bring together a collection of first-hand experiences, told from the perspective of those who knew they were facing a finite amount of time left. They came from England, Wales, Northern Ireland, New Zealand and Canada. The youngest was 28, the oldest was 94.

Peoples health and circumstances will continually change, so I have kept the dates and information correct to the time of each interview.

Some names, ages and locations have been modified for anonymity.

Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?

Mary Oliver

IF YOU ONLY HAD ONE YEAR...

If you only had one year to live, what would you do with it?

If you only had one year to live, would you be happy with the choices youve already made and the life youre already living? Would you be happy with the relationship youre in, with the friends you have, with your health and the body you inhabit, with the work you do?

Is there anything you would change?

Is there anything you think you might regret?

For me, that list of regrets was endless. But I didnt have a year to live, it was much shorter than that. The surgeon who saved me told me the next day that I only had about five minutes left. Five minutes between life and death. Its a hard thing to comprehend, even now.

I was 37 and found myself being wheeled through a never-ending hospital corridor towards an operating room. Id had an ectopic, a pregnancy where the fertilised egg implants itself in the fallopian tube, rather than your womb, making it rupture and in my case causing major internal bleeding.

It was my second ectopic, so Id lost another baby too. At least now Id be symmetrical. Tubeless, but in balance.

Its strange, the jumble of things you remember when you cant think straight: the ward sister forcing me to open the curtains every morning, my heart beating a little faster to push my newly acquired blood around my body. Feeling my organs shut down, wanting the pain to end, but also not wanting the doctors to touch me. Realising I was now unable to have more children.

I asked if there was anything else they could do? No, they replied.

I was living in New Zealand at the time with my husband and our two-year-old daughter, having escaped London in search of a better life. And it was better, for a while. On the plane there, I remember looking down at our new country, thinking how I wanted to conquer her. The same way I had wanted to conquer London when I moved back after six long years stuck in a little seaside town on the south coast of England.

It didnt happen, of course, because my life wasnt a mid-budget movie from the 1980s. And I wasnt Michael J. Fox. Or Melanie Griffith.

I was in a relationship that didnt quite work, living in a place where I didnt feel truly comfortable. My work was going nowhere slowly and what little headspace I had left was consumed with trying to have another child.

I felt ordinary. Easily forgettable. Locked into standby mode.

This was not how I imagined things would be.

This was not how I expected to spend my one wild and precious life.

I was born in Central London when the IRA cleared school playgrounds with bomb threats and artists could afford to live there. My dad, who is half-Romani Gypsy, was a sculptor. My mum, a dinner lady. We lived above our nan and grandads corner shop a place that not only delivered newspapers to all the big hotels throughout the West End, but also ran an under-the-counter bookies. A step up from my great nan, who was a bare-knuckle fighter around the pubs of Birmingham. (Yes, really.) But I dreamt of something different. Of a fulfilling career. Of a garden full of lupins and hollyhocks, of a house flooded with light. Of being in love. Of motherhood. Of never having to worry about money like my mother had had to worry about money.

Impatient and hungry, I would make rash and risky decisions in a bid to get to my bright and shiny future in the quickest way possible: I ran away from home at 14, got engaged at 15 and moved back to London at 16. On my eighteenth birthday I went to bed and cried. It was as if I could hear time passing, like I could physically feel it slipping through my fingers. I felt I should have done more by now, I should be more. Mondays were where diets were born. Bigger plans were reserved for 1 January. Everything good and wonderful seemed to happen in a future I never quite seemed to reach. It was like I was constantly waiting for my real life to start.

This time next year, I would be happy. Maybe.

Id always kept lists. Lists of things to see, lists of things I wanted to do, all written in bullet point style, ready to be ticked off the second they were completed. They had kept me ordered and on track, but the moment I arrived in that hospital they suddenly felt like a reminder of all the things Id failed to do. In reality, lots of major boxes had been checked marriage, home, motherhood but all I could see were the spaces that remained empty.

After four days and a blood transfusion, I was released from hospital. My body was alive and well, but my mind was struggling. I was lost in a constant fog of questions, reproaching myself for all the things I hadnt done yet and all the years I had wasted.

Was this it? Where had all the time gone, and what had I done with it?

It felt like only yesterday I was sneaking into the Camden Palais or having drunken trolley races down our local high street. Now, I was heading towards 40 with lots of jobs behind me, but no career; lots of addresses lived in, but no place to call home. I knew I should have been happy to be alive. I knew I should have felt grateful, but instead I just felt guilty that I didnt. And every unticked box became a question of what if . What if I had done this? What if Id made this choice instead of that one? I would watch my daughter do things, hit milestones, and I would think, Im so lucky to be here. Im really, really lucky. Yet, deep down my overriding thought was, Why? Why was I still here if I wasnt going to change things? What was the point of being alive unless I was really going to live?

Youd think Id become braver. Bigger. More fearless. Well, the honest truth is I didnt. I didnt die at 37, but neither did I really start to live. Id been given a second chance but I couldnt seem to get going, I just let the fog settle around me.

A year after I was discharged and in the clear, we moved back to the UK. Our daughter started school and my husband set up his own business. Somehow, half a decade had been spent. But I was still stuck in the lonely anger of it all, collecting more and more regrets as the days, weeks and months passed by.

I did try to find a way out.

I joined a netball team; I went to therapy; I made new friends. I tried lots of different ways to try and join in with life again but none of them seemed to work. So, I made a decision: instead of avoiding how I felt, I would face it head-on instead.

I searched for real stories that would remind me that life was something to be cherished. Not necessarily from people who were recovering from a near-death experience like me, or from those who had lived an error-free life, but from people who were perhaps nearing their own end. People who were willing to share, in hindsight, how they felt about the choices theyd made and the things they wanted the rest of us to realize before its too late.