Copyright 2012 Ion Inc.

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication, reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system without the prior written consent of the publisheror in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, license from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agencyis an infringement of the copyright law.

Doubleday Canada and colophon are registered trademarks

Library and Archives of Canada Cataloguing in Publication is available upon request

eISBN: 978-0-385-67927-5

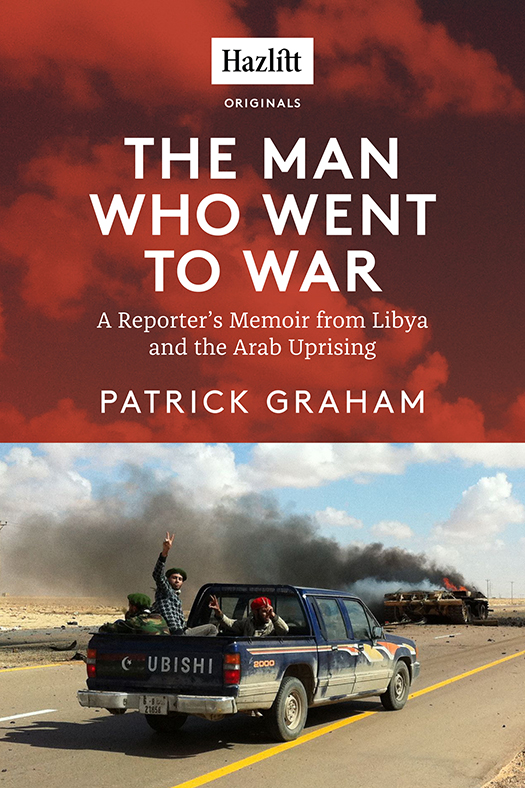

Cover design: Michle Champagne

Cover photo Patrick Graham

Published in Canada by Doubleday Canada,

a division of Random House of Canada Limited

www.randomhouse.ca

v3.1

Hazlitt Originals

A new series of original, commissioned e-books of varying length and subject matter, featuring both established and emerging authors from around the world. From investigative journalism and fiction, to travelogues, polemics, and interactive tablet creations, Hazlitt Originals aspire to push the boundaries of story form.

Titles in the series

Braking Bad: Chasing Lance Armstrong and the Cancer of Corruption, by Richard Poplak

The Gift of Ford: How Torontos Unlikeliest Man Became its Most Notorious Mayor, by Ivor Tossell

You Arent What You Eat: Fed Up with Gastroculture, by Steven Poole

The Man Who Went to War: A Reporters Memoir from Libya and the Arab Uprising, by Patrick Graham

Contents

1.

At the end of February 2011, I was in the kitchen making breakfast for my nephew and brothers-in-law and their girlfriends. The Arab world was in revolt and I was half paying attention, handicapping the horses like a retired jockey who still thinks about going back to the track. My wife and I had invited the others skiing for their March break, which involved a lot of driving and cooking for me and a lot of sleeping for them. They were in their early twenties and had their girlfriends with them and no reason to get out of bed even if they were awake, which in this daylight-challenged season was a very narrow window.

The radio was on and I was talking to the news. A reporter was driving me crazy. The day before my tone toward him had been encouraging, collegial even, but now I was getting sarcastic and raising my voice slightly, probably sounding a bit marital. The town of Benghazi in Eastern Libya had liberated itself from Gaddafi a week earlier and this journalist was still at the Egyptian border. I pictured him dangling his legs from a fence. At the Egyptian-Libyan border was not a credible dateline at this point. The revolution was going to be over soon.

If youre a recovering journalist, you know, with the kind of arrogant certainty that irritates your wife in other circumstances, what you would be doing during these moments because youre already there in your head. I had stopped reporting on warswith a few relapseswhen Id left Iraq more than half a decade earlier. It hadnt been that conscious a decision. Friends would e-mail from somewhere and I wouldnt be in the least envious. But that didnt mean I wasnt casting a professional eye on events and projecting myself into the mix. I may have been at home, but my avatar had been doing some heroic work around the globe. That morning, by the time Id made the pancake batter, this avatar had left Benghazi and was moving west with the advancing rebels. Soon hed be in Tripoli taking the fight to Gaddafi.

One thing was for sure, my avatar was not sitting on the border fence with the radio journalist, which is why the real me was wearing an apron and mocking the guy from a kitchen in Quebec, For fucks sake, at least get to Benghazi. It was around that time that my wife, who had walked in unnoticed, said, Why dont you go? She could have said it as a taunt but her tone was very sweet. She seemed genuinely curious.

Rome in the winter rain is very unpleasant, which is why most of the carabinieri guarding the Libyan embassy on Via Nomentana were across the street having a pizza lunch. It was a week after the radio debate in Quebec, and I had headed off to beat my avatar to Tripoli. A friend of mine, Pier Paolo (an astounding number of Italian photographers are called Paolo or Pier Paolo, just as lot of the French ones are named Jrme), pulled up on his motorcycle and we went into the embassy. Romes was one of the few embassies in the world still issuing Libyan visas, needed for those parts of the country controlled by Gaddafi. I had been in Baghdad when the U.S. Marines arrived to overthrow Saddam, and my first instinct now was to go to Tripoli. The capital tends to be where the action happens. But as soon as we were inside the gatehouse, I knew Id have to leave the city to my avatar.

To begin with, the visa application was in Italian. But it was the look of the moustachioed regime-type behind the desk that confirmed my suspicion. Id seen that look often enough in Syria and Saddams Iraq. It was a kind of Baathist stare. To get into a dictatorship that is under threat you need an inside connection, with, say, a corrupt foreign company that has already bribed the government officials (I can think of at least one Canadian company that could have helped me), or with someone in the regime who thinks you might be a useful idiot who can be manipulated. Visas of this kind are inevitably a dirty handshake, but in the embassy gatehouse no one was reaching out to me.

Shelving Plan A, I went back to my hotel and just lay on the bed. I had forgotten what a depressing business this could be. No job, no visawhat was I thinking? I phoned my wife.

From the beginning, wed had very different views of the Arab Awakenings. I had lived in Iraq for a few years as the country fell apart and, perhaps unfairly, I was pessimistic about the chances for the region over the long term. It seemed to me trapped by too many forces and dependent on too many variablestoo many people, too little water, too much history, too many foreign interests.

But my wife loved Egypt, and when President Hosni Mubarak had resigned a few weeks before, shed cried and talked about the soul of a country. I was thinking military coup and 80 million people on a river, with no work, surrounded by desert. My sense was that even if the Egyptians got it together, wed screw it up for them. Im told the Arab world has a term for this now: al-Hala al-Iraqiya, or The Iraqi Situationto become as screwed up as Iraq, thanks to the West.

True, Tunisia had gone pretty well up to this point. But Tunisia was supposed to have topless beaches, or at least speak French. It was hard for me to imagine a place with Club Meds getting too Iraqiya. Except, of course, Lebanon, which had once been a Club Med of Iraqiya. But the Lebanese civil war was one more argument in my favour. Egypt, I thought, could still go either way. Yemen, the most heavily armed population in the world, was starting to revolt too, which threatened to bridge the gap between Iraqiya and total annihilation. I had once eaten at a restaurant on the highway between Aden and the capital, Sanaa, and all the other customers had Kalashnikovs on the tables beside them, as if theyd taken their guns on a lunch date. Then they went and got really high on khat.

And there was Libya. The problem with Libya was that it wasnt on our planet. It was like hearing Pluto was trying to free itself from a Martian. Who knew anything about the place other than Gaddafi and his fabulous, extraterrestrial weirdness? I had grown up on reruns of the 1960s TV show