Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2019 by Alan Brown

All rights reserved

First published 2019

E-Book edition 2019

ISBN 978.1.43966.779.8

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019940048

Print edition ISBN 978.1.46714.167.3

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Storytelling had been an integral part of Alabamas cultural fabric for centuries before its statehood. Alabamas first inhabitants, the Choctaws and Cherokees, passed down tales about geographical landmarks, such as Chewela Creek and Noccalula Falls, and great warriors, such as Tuskaloosa and Tecumseh, for centuries. Tales of Prince Medoc, the great Irish explorer, entered the Native Americans storytelling traditions around the year 1100 CE. By the end of the 1800s, Alabamas legends were heavily influenced by the contributions of the Scotch-Irish settlers and African American slaves. In the absence of movies and television, storytelling became an important form of entertainment for people living in small towns, big cities and college campuses.

One could argue that folklore collecting in Alabama began with Martha Strudwick Young (18621941). She was the daughter of Confederate physician Elisha Young and niece of Alabama reformer Julia Tutwiler. After she graduated from Livingston Female Academy and Normal School, Young embarked on a writing career. In 1884, she began publishing collections of folk tales and legends she had heard from African Americans while growing up in Greensboro, Alabama. Her eight books of folk tales and songs feature black protagonists. Written in black dialect, Youngs works, like Behind the Dark Pines (1912), established her as a regional writer and allied her with other dialect writers, like George Washington Cable and Joel Chandler Harris. By the time she died, Young was known as Alabamas foremost folklorist.

The next serious collector of Alabamas legends was Carl Carmer (18931976), who taught at the University of Alabama from 1927 to 1933. During this time, he traveled throughout the state, interviewing the folk of Alabama in an attempt to create an accurate picture of the real Alabama. Many of his subjects, like Ruby Pickens Tartt from Sumter County, told him tales of outlaws, hood doctors, ex-slaves, folk songs, midwives and Civil War battles. The resulting work, Stars Fell on Alabama (1934), became a bestseller, owing its success, in part, to the books conversational and, at times, poetic style

Although families had been passing down local tales to their children and grandchildren for generations, the preservation of the states legends and folk tales had not been undertaken on a large scale until the late 1930s. On July 27, 1935, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed into law the Federal Writers Project, which hired over ten thousand clerks, writers, researchers, editors, historians and scholars to collect oral histories, local histories, life histories, city guides, state guides, ethnographies and other works. Many of the interviewers attempted to re-create the storytelling sessions for the reader by faithfully reproducing the dialect. A number of Alabamas signature legends, like The Face in the Window of the Pickens County Courthouse, first appeared in these collections that eventually found a permanent home in the Library of Congress. An ancillary project, the Slave Narrative Collection, was conducted between 1935 and 1939. The final collection consists of interviews with 2,300 ex-slaves and five hundred photographs.

In the late 1960s, folklore writers presented the legends of Alabama to an entirely new audience by rewriting the standard tales and giving them an artistic flair. One of the most popular of these collections, 13 Alabama Ghosts and Jeffrey (1969), was written by two Alabama natives, Margaret Gillis Figh (18961984) and Kathryn Tucker Windham (19182011). This highly successful anthology of thirteen of Alabamas most enduring ghost tales was followed by a number of other successful books, including Jeffreys Latest Thirteen (1982) and Alabama: One Big Front Porch (1975). Together, these books are a very loose collection of legends from the entire state.

I had the privilege of knowing Ms. Windham. On our trips from her home in Selma to the main stage at the Sucarnochee Folklife Festival in Livingston, she regaled me with stories about antebellum churches and old diners along Highway 80. On one of our drives, I referred to her as a folklorist, and she immediately corrected me. I have no formal training as a folklorist, she said. Im just a storyteller. It made me sad to think that so many of Alabamas stories were never published and, therefore, would never be told to future generations.

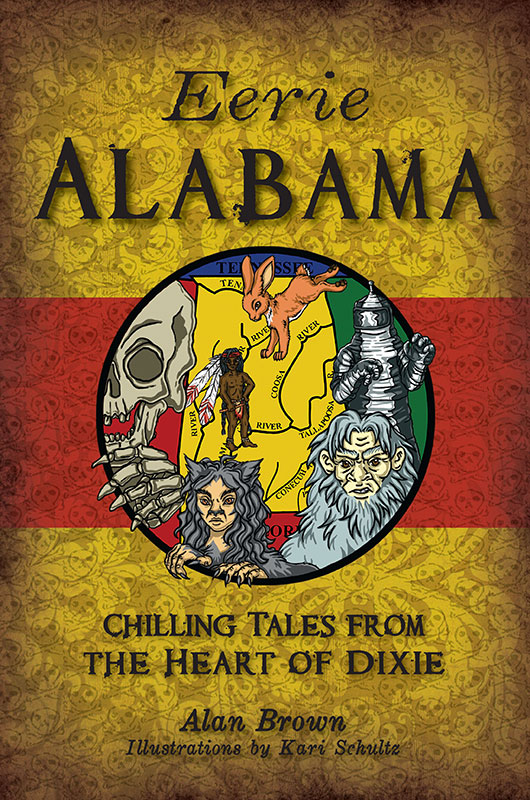

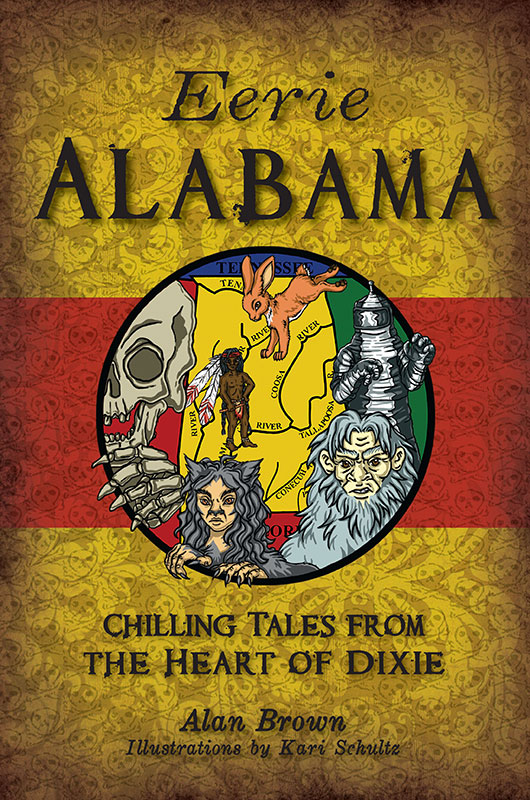

Eerie Alabama represents my attempt to continue the work that Ms. Windham started in Alabama: One Big Front Porch in 1975. Most of these stories would have been perceived by the teller and the listener to be true. Indeed, these tales conform to the Brothers Grimms definition of a legend being historically grounded. A few of these stories are updates to Ms. Windhams, such as the chapter on the college legends. Others are closer to mysteries, such as The Strange Case of Orion Williamson and The Disappearance of Harris Rufus Loggins. Only a handful of these legends are probably apocryphal, like the story of Gasparilla the Pirate or the Mobile Leprechaun. One of the most tantalizing aspects of many of the more fantastic tales is the lack of empirical evidence, like in the tale of Alabamas buried giants.

I hope you enjoy this representative sampling of the oral histories of communities spread throughout Alabama. If these versions of the tales differ from the stories you know, keep in mind that they have been embellished over the years through constant retellings. A little piece of the storytellers is reflected in their contributions to the oral tradition. Therefore, there is no single correct version of a legend. Because myths and legends are repositories of the states values, history and geography, they should all ring with a note of familiarity.

I

MYSTERIOUS MONSTERS

THE WHITE THANG OF ALABAMA

For generations, people have associated Bigfoot with the Pacific Northwest, where native tribes relayed tales of hairy men years before the arrival of white settlers. Indians living in North America had more than sixty different words for the monster. In the 1840s, Native Americans living near present-day Spokane, Washington, told missionaries stories of a larger-than-life creature that lived in the mountains and stole salmon from their nets. In the 1920s, a Canadian newspaper reporter gave the creature a nameSasquatch, an anglicized form of a Halkomelem Indian word meaning wild man. Interestingly enough, only one-third of all Bigfoot-sighting claims have been located in the Pacific Northwest. Bigfoot sightings have also been reported in the Great Lakes region and in the southeastern United States. In 1972, the movie

Next page