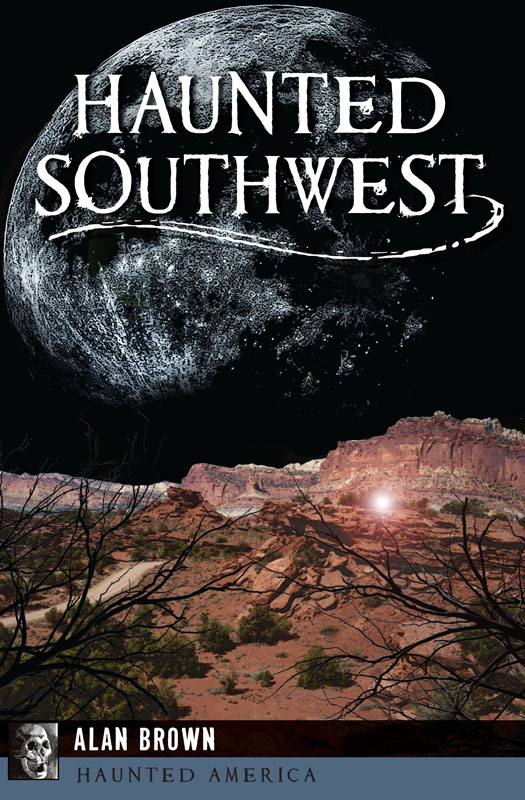

Published by Haunted America

A Division of The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2016 by Alan Brown

All rights reserved

First published 2016

e-book edition 2016

ISBN 978.1.43965.871.0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016933576

print edition ISBN 978.1.46713.757.7

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To my father-in-law, Paul Quick, who loves the Southwest and western lore as much as I do.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Christen Thompson, senior acquisitions editor at The History Press, who provided me with invaluable support and advice during the writing of this book. I am also deeply indebted to my wife, Marilyn, who accompanied me on my story-collecting trips to Texas.

INTRODUCTION

The American Southwest is a land of broad vistas and tall tales. Ever since the explorer Francisco Vazquez de Coronado led an expedition to the Seven Cities of Cibola in the early sixteenth century, the lure of the Southwest has attracted millions of people to this storied land. The first English trappers made their way to Arizona in 1825, paving the way for thousands of pioneers who filled their wagons with their families, their possessions and the dreams for a better life. Following the Civil War, thousands of ex-slaves, tantalized by the freedom of the Southwests wide-open spaces, flocked to this region. A legion of exConfederate soldiers headed west as well in the hope of making a fresh start. Watching this seemingly endless parade of immigrants were the Native Americans, who had occupied the Southwest since the arrival of the Clovis culture around 9000 BC. All of these different groups brought with them their own traditions. Over the years, these different groups shared their stories, producing a rich array of legends that are still told to this day.

The geography of the Southwest figures prominently in many of these tales. However, ghosts are just as likely to be found in hotels, restaurants, universities and courthouses as they are in canyons, arroyos and wide prairies. Ghost stories, it seems, can be generated in any setting where people live and work.

Of course, ghost stories are much more than accounts of paranormal incidents. In these narratives, populated by jilted lovers, lonesome cowboys, duty-bound soldiers, bold outlaws, Hispanic entrepreneurs and displaced Native Americans, one can find the same high drama that appears in more formal literature. Their hopes, dreams and disappointments connect these people to us in a very personal way. The American Southwest may seem at first glance to be a far-away place lost in time, but it is actually much closer to home than one might think.

ARIZONA

BULLHEAD CITY

Hardyville Pioneer Cemetery

Founded in March 1864, the city was originally called Hardyville after William Harrison Hardy, who was a politician and the operator of a ferryboat on the Colorado River. Steamboats traveling up the Colorado River from Port Isabel stopped at Hardyville to deliver supplies to the gold, silver and copper mines. Hardyville became the starting point for pack trains and wagons traveling to the mines between twenty and thirty miles away. As the profits from mining soared in the 1870s, Hardyvilles prominence escalated, even though the town was nearly destroyed by two devastating fires in 1872 and 1873. It even served as the county seat from 1867 to 1877. Hardyvilles decline began in the 1880s as the price of silver began dropping. The port became obsolete in 1883 when the ferry was moved to Needles, California. By the turn of the century, the ferry had been moved to Needles, California, and Hardyville was a ghost town, its glory days a distant memory. Hardyville was resurrected as Bullhead City with the construction of the Davis Dam between 1942 and 1953. Today, it is a thriving modern city with two hospitals, an international airport, a community college and, some say, a haunted cemetery.

Hardyville Pioneer Cemetery is the last important remnant of the once thriving port city. The 2.5-acre cemetery is located at 1776 Arizona State Route 95 on a bluff overlooking the Colorado River. The old cemetery is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Local historians estimate that the cemetery contains between sixteen and twenty-four graves. However, the website www.FindaGrave.com lists only ten known graves and one unknown: Adelia Amaro, Charles Atchison, Edwardo Bernol, Robert Keffin, John Killian, G.E. Mathew, A.O. Perkins, William Taylor, Samuel Todd and William J. Tuttle. All of these people were interred between 1866 and 1898.

Despite the fact that Hardyville Pioneer Cemetery is located in a residential district facing a Safeway, it has an abandoned look. Weeds grow between the cobblestone-covered graves. Rumors of paranormal activity within the cemetery began after heavy rains washed several coffins out of the ground. The remains were reinterred, but their spirits appear to be unhappy about having their eternal sleep disturbed. Paranormal investigators using dowsing rods indicated the presence of spirits by pointing in different directions. Ghost Seekers Paranormal, a paranormal group, recorded two interesting EVPs (Electronic Voice Phenomena): the crying of a baby and a male voice whispering, Hello, Maam. It is small wonder that in the late 2000s, the cemetery was featured on the Haunted Laughlin Tour.

KINGMAN

Luanas Canyon

One of the Southwests most tragic tales is the story of Llorona, a Hispanic woman who took vengeance on her unfaithful lover by drowning the children she had out of wedlock. A story about another wailing woman is told in Kingman. The legend of Luanas Canyon serves as a reminder of the travails of miners and their families in the nineteenth century. According to the standard version of the story, a miner lived in a small wooden shack in a canyon just outside Kingman with his wife and children. He provided for his loved ones by making forays into the mountains, looking for gold and other precious minerals. He returned to the shack every two weeks with enough food to last his family until he returned. The story goes that, eventually, he failed to return home at the prescribed time. Some storytellers believe that he was killed by Indians, robbers or wild beasts. Without the supplies they depended on, his wife and children began to starve. Before long, the distraught woman could no longer look into their wan faces or listen to their pathetic whimpering. One fateful night, her mind snapped. Wearing her snow-white wedding dress, she grabbed a hatchet and chopped up her sleeping children into small pieces. Within minutes, the once homey little cabin had been turned into a slaughterhouse. Splattered with blood, the woman gathered up the remains of her children and staggered out to the river. She dumped the body parts into the river and then sat on the riverside, tearing out clumps of hair and wailing pitifully. Within a couple of days, the poor madwoman succumbed to starvation, a victim of the rigors of life in the unforgiving desert.

Next page