Stilwater

Stilwater

The names of animals, people, and places in this book have been changed to protect privacy.

2014, Text and photographs by Rafael de Grenade

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher: Milkweed Editions, 1011 Washington Avenue South, Suite 300, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55415.

(800) 520-6455

www.milkweed.org

Published 2014 by Milkweed Editions

Cover design by Brad Norr Design

Cover photo and interior photos by Rafael de Grenade

Author photo by Jaime de Grenade

14 15 16 17 18 5 4 3 2 1

First Edition

Milkweed Editions, an independent nonprofit publisher, gratefully acknowledges sustaining support from the Bush Foundation; the Patrick and Aimee Butler Foundation; the Driscoll Foundation; the Jerome Foundation; the Lindquist & Vennum Foundation; the McKnight Foundation; the National Endowment for the Arts; the Target Foundation; and other generous contributions from foundations, corporations, and individuals. Also, this activity is made possible by the voters of Minnesota through a Minnesota State Arts Board Operating Support grant, thanks to a legislative appropriation from the arts and cultural heritage fund, and a grant from the Wells Fargo Foundation Minnesota. For a full listing of Milkweed Editions supporters, please visit www.milkweed.org.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Grenade, Rafael de, 1980

Stilwater : finding wild mercy in the outback / Rafael de Grenade.

pages cm

Summary: Set on an abandoned cattle ranch in Queensland, Australia, this memoir explores the power of a beautiful coastal landscape, contrasting this place with the brutality of modern ranching, and exploring the tension between wildness and human efforts to create order from itProvided by publisher.

ISBN 978-1-57131-888-6 (ebook)

1. RanchingAustralia. 2. Feral cattleAustralia. 3. Grenade, Rafael de, 1980TravelAustralia. 4. AustraliaDescription and travel. I. Title.

SF196.A8G74 2014

994.38072092dc23

2013043098

Milkweed Editions is committed to ecological stewardship. We strive to align our book production practices with this principle, and to reduce the impact of our operations in the environment. We are a member of the Green Press Initiative, a nonprofit coalition of publishers, manufacturers, and authors working to protect the worlds endangered forests and conserve natural resources. Stilwater was printed on acid-free 100% postconsumer-waste paper by Edwards Brothers Malloy.

To Soraya, with love.

Contents

Stilwater Station

Gulf Country

I LANDED ON STILWATER in the dry season. I arrived by air, sweeping across white savanna mottled with sand ridges and the speckled green of vegetation. From above, the upper reach of the gulf country was a paintingtracings and patterns with vivid colors and no distinct shapes, the future and past laid out below all at once, temporal paths cut by countless spirits on walkabout, here and gone.

Trees took shape as the plane descended, tall, with blue-green willowy canopies, and then a small station rose up, a compound with a few rectangular scattered buildings, a few corrals at the end of a long white line of road leading in from the east. The pilot veered, dipping one wing, and then a long dirt strip appeared and there was no avoiding the ground. The small wheels jolted against hard-packed earth and yellow grass blurred past the windows.

When the pilot opened the curved door, I climbed down over the wing. I had arrived alone, the sole passenger. The searing white earth rose to meet me.

Australia is an island between two oceans, a landmass isolated for some fifty-five million years. Most of the twenty million people there today choose the tranquilizing lip of deep blue water at the eastern rim. But farther inland, farther north, red earth and black earth, hot savannas of eucalyptus trees and bronze desert reveal the continents heart. This subtle expanse reaches for days of flat nothingness, the creases of thin drainages like wrinkles of skinparched, leathered, endless.

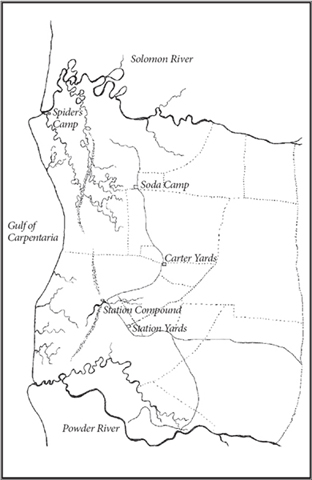

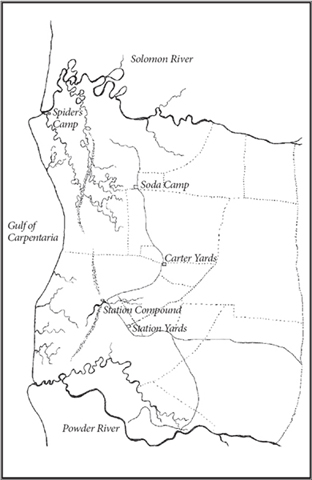

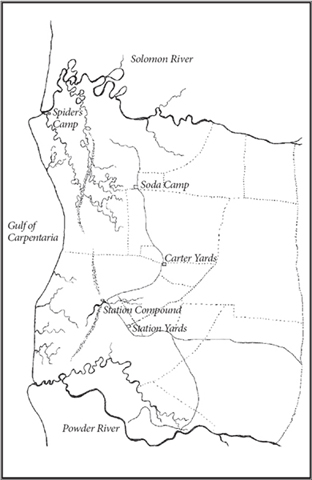

Hours from the cities on the coast, across the barren sweep, a horn juts upward on the northeastern corner: the spiked protrusion of the Cape York Peninsula, which reaches almost to Papua New Guinea. Here the earth begins to green again, just the palest tinge of tropics clawing onto the flattest land on earth. In its farthest domain, the horn cuts between the Arafura Sea in the Indian Ocean and the Coral Sea of the Pacific Ocean. Retreat a little to the south and west and the Arafura Sea bleeds into the Gulf of Carpentaria. Stilwater Station is a rectangle that borders the sea and covers a swath of the coastal plains.

The gulf country is alternately, and sometimes all at once, a rippling savanna, a salt flat, and a scrub whose edges endlessly change and play at the wide silk of the sea. Rivers snake across it in broadening oscillations, resisting the moment they become one with the glittering ocean, trying to slow down time. Shallow channels cut between the major conduits, where, depending on rain and the direction of storms, water can flow in either direction. Salt arms reach inward like the limbs of an octopus, their tentacles fringed in mangroves.

This land is a body without boundaries, filled with veins that transgress and regress, feeding and starving its different organs with impunity. In other places, rivers are dependable, land is dependable. This is a landscape where anything can happen. A place that defies human nature, and even seems to defy nature itself.

Few places on earth have a single tide each day, but in the gulf, two oceans collide in what feels like a conscious rebellion against physics and gravity, and the combined forces cancel a tide. Rivers flow out to the gulf for half of the day and the gulf flows into them for the other half. The tide pushes upstream, miles inland, blending salty and sweet.

The gulf is not inviting. More like luringfull of sharks and jellyfish and silver barramundi. Crocodile eyes follow any creature that ventures to the shore, but not many do. Most know to give the coastline a wide berth, and the waters ripple alone. Low tide exposes white beaches and sandbars with shallow water spreading in translucent, jade-green fi ns between them. The crocodiles sleep on the warm sand just above the surf, deadly and serene.

Inland, forested bands of sand ridges dissect the grasses and flats. Low ridges appear and disappear across the plain, sections of old waterways left a few feet higher than the surrounding country after millennia of erosion. Tall waving grasses sweep several feet high in faded gold between open forests, brackish lagoons, and murky bogs. Saltwater mangroves line the coast and saline rivers; freshwater mangroves grow on stick legs along the swamps. Water lilies raise white and purple palms in the lagoons in rare, delicate gestures. Sea wind blows in from the coast, cool on the winter mornings. Sea eagles haunt the line between sand and sea while wallabies fidget and nibble and bounce, a foot tall and easily frightened. Huge lizardsgoannasprowl the scrub and snakes trace wandering lines into the sand.

Next page