Contents

I bring Naya into the Magic Kingdom. Naya is my

Standing upright on the mantel is a tray my old

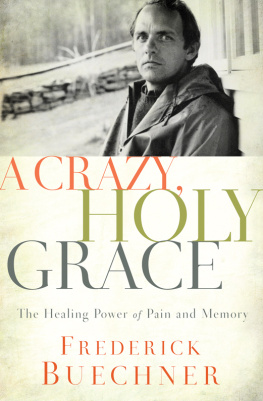

As you enter the Magic Kingdom, biographies are immediately to

The half of the library you enter first is where

Sick with anxiety, depressed, doom-ridden, I was parked once in

I wonder sometimes what will become of the Magic Kingdom

In addition to the autographed photograph of Anthony Trollope that

St. Paul, or whoever it was, wrote to the Ephesians

I bring Naya into the Magic Kingdom. Naya is my grandmother, my mothers mother, who died in 1961 in her ninety-fourth year. She walks across the green library carpet and stands at the window looking out across the stream toward my wifes vegetable garden and the rising meadow behind it with a dirt track running through it up into the sugar woods on the hillside.

The Magic Kingdom is my haven and sanctuary, the place where I do my work, the place of my dreams and of my dreaming. I originally named it the Magic Kingdom as a kind of jokepart Disneyland, part the Land of Ozbut by now it has become simply its name. It consists of the small room you enter through, where the family archives are, the office, where my desk and writing paraphernalia are, and the library, which is by far the largest room of the three. Its walls are lined with ceiling-high shelves except where the windows are, and it is divided roughly in half by shoulder-high shelves that jut out at right angles from the others but with an eight-foot space between them so that it is still one long room despite the dividers. There are such wonderful books in it that I expect people to tremble with excitement, as I would, on entering it for the first time, but few of them do so because they dont know or care enough about books to have any idea what they are seeing.

They are the books I have been collecting all my life, beginning with the Uncle Wiggily series by Howard R. Garis. In 1932, when I was six, I sent my unfortunate mother all over Washington, D.C., looking for Uncle Wiggilys Ice Cream Party , but she never found it, and it wasnt until about sixty years later that I finally located a copy and completed the set. There are first editions of all the Oz books, some of them the same copies I read as a child, with Frebby Buechner scrawled in them because I was less sure about the difference between b s and d s in those days than I have become since, and also of both Alice in Wonderland and Alice Through the Looking Glass , with a later edition of each signed by the original Alice herself when she came to this country in 1932 as an old lady to receive an honorary doctorate from Columbia University on the centenary of Lewis Carrolls birth. Underneath her academic robes she wore a corsage of roses and lilies of the valley and in her acceptance speech said she would prize the honor for the rest of my days, which may not be very long. She died in 1934 at the age of eighty-two. There is a drab little Jenny Wren of Dickenss A Christmas Carol as first published in 1843 with green endpapers and the four hand-colored, steel-engraved plates by John Leech, and a Moby Dick or The Whale in the original shabby purple-brown cloth with the usual moderate foxing throughout, as the catalogue description apologetically notes. There are a number of seventeenth-century folios, including the sermons of Lancelot Andrewes, Jeremy Taylor, and John Donne, that I started buying when my wife and I were on our honeymoon in England in 1956 with some British royalties that were due me then. There is Norths Plutarch and Florios Montaigne and the first collected edition of Ben Jonson, 1692, which I was beside myself with excitement to discover bore the inscription Jo: Swift, Coll Nova in an eighteenth-century hand, only to learn from the British Museum years later that it was not, as Id wildly hoped, the great Jonathan but one John Swift, who matriculated at New College, Oxford, at the age of fifteen.

On the walls are the framed autographs of some of my heroes. There is a photograph of the portrait of Henry James that his friend Sargent painted on the occasion of his seventieth birthday, inscribed by both Sargent and the Master himself, who distributed prints of it to the faithful. Nearby Anthony Trollope has signed his name together with the words Very faithfully beneath a carte de visite photograph that shows him in granny glasses scowling through whiskers that erupt from his face like the stuffing of an old sofaall gobble and glare, as Henry James once described him in a letterand there is a sepia cabinet photograph of Mark Twain on the lower margin of which he has written, It is your human environment that makes climate, whatever exactly he meant by that. And then, matted with red damask in a gilt frame, there is the upper part of a sixteenth-century vellum document in which Queen Elizabeth, the only real Queen Elizabeth, grants permission to someone whose name I cannot make out to travel to Flanders on official business. When the trip was completed, the document was canceled with four gill-like incisions, and at the top of the page the queen signed it Elizabeth R. Between her signature and the documents first line there are two free-floating squiggles, which my wife and I long ago decided mark where she tried out her quill pen to make sure it wouldnt spatter ink when she made the great flowing loops that fly out like pennants in the wind from the bottom of the E and Z and R and the upper staff of the B .

On the sash of the large window at the end of the room, where Naya stands waiting for me to get on with my description, there is a stone I found wedged into a crack in the rocky ledge we stepped ashore on when I made a pilgrimage to the island of Outer Farne in the North Sea one summer in honor of St. Godric, who often visited there in his seafaring days in the twelfth century and about whom I had written a novel several years earlier. In the novel I describe how on his first visit to the island Godric ran into St. Cuthbert, who had died some four hundred years before. Cuthbert says that long before Godric arrived, he was expected there and then explains himself by saying, When a man leaves home, he leaves behind some scrap of his heart. Is it not so, Godric?Its the same with a place a man is going to. Only then he sends a scrap of his heart ahead. When I finally managed to pry the stone loose with my pocketknife, I discovered, to my wonderment, that it was unmistakably heart-shaped, and I have fastened Cuthberts explanation to the back of it with Scotch tape. On top of one of the divider bookshelves is a Rogers Group that depicts King Lear awakening from his madness in the presence of his old friend Kent, disguised as a servant, and the Doctor, and Cordelia, whose forehead he is reaching out to touch as he says, in the words inscribed on the statues base, You are a spirit, I know. When did you die? On the windowsill stands the bronze head of my childhood friend, the poet James Merrill, sculpted in the summer of 1948, when we shared a house on Georgetown Island in Maine while he worked on his First Poems and I on A Long Days Dying , which was my first novel. I remember feeling rather miffed that it was Jimmy rather than I whom our friend Morris Levine had chosen to immortalize, but I got over it.

Naya is sitting in the wing chair by the window looking as she did when she was in her late eighties. Her eyes mid many wrinkles, her eyes, her ancient, glittering eyes, are gay, as Yeats wrote of the old Chinamen in Lapis Lazuli. Her hair is in a loose bun held together by several tortoise-shell pins, and there are a few stray wisps floating free. She is wearing a black dress with a diamond bar pin. One hand extends out over the arm of the chair, palm upward, and she lightly rubs her thumb and middle finger together with a circular motion, as she often did when she was waiting for something to happen.