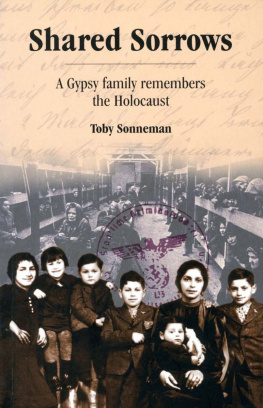

The Scholar Gypsy

The Quest for a Family Secret

Anthony Sampson

For Dorothy and John,

my sister and brother,

who shared the puzzle

1

The Silence

As a child I had only a hazy memory of my grandfather John Sampson. Not long before he died in 1931, when I was aged 5, he came to stay with us in Hampstead for the wedding of my aunt Honor: I can still visualize a formidable but magical old man with a big bald head and strong chin, who played with us in the garden. But after his death his spirit seemed to hover as a shadow over both my parents.

My mother would sometimes talk about him with a dread which could only fascinate a child about his ferocious temper, his heavy drinking, his wicked but unstated habits, and about a woman in Liverpool, the wretched Dora, who apparently stood between him and our family. Yet our house also contained relics which provided more attractive clues, including a fine romantic drawing of him by Augustus John and another of a gypsy gazing at a seductive girl; a book of gypsy folktales; and a daunting Oxford dictionary of the Romani language, compiled by John Sampson.

That gypsy hinterland naturally aroused the curiosity of a child. My mother told me how the gypsies called my grandfather the Rai, the gentleman or scholar. But my father was always reluctant to talk about him or anyone else for that matter for he was a reticent man who found fulfilment in his work as a scientist and retreated into silence at home. My childs instinct sensed there was something unresolved in our background which separated us from less reserved families.

As I grew into my teens I began to feel this tension more strongly: that the family was under a curse for which the mysterious Rai was somehow responsible. He seemed to hold a spell over anyone who had known him, to be always linked with those mysterious gypsies. Yet his memory in the family seemed to have gone up in smoke, like a caravan at a gypsy funeral. And the travellers world itself the brightly painted horse-drawn wagons on lonely roads, the wild-haired musicians playing round camp-fires was being obliterated by the relentless expansion of suburbs and motor cars, or tamely imitated by Boy Scout camps and mass-produced caravans.

Among the relics of my grandfather in our house I came across a folder full of yellowed press cuttings. They told of his funeral on a Welsh mountain and conjured up a bright vision of that vanished world and his own part in it, and of intense friendships and loyalties which raised all kinds of questions. From them I pieced together the strange story which in 1931 had briefly dominated the headlines of the popular papers.

They told how on the morning of 21 November an extraordinary gathering of mourners converged on the small Welsh village of Llangwm just below Foel Goch, the Red Mountain, where my grandfather had asked for his ashes to be scattered. The mourners included my father and an odd mixture of gypsies and scholars, the former Lord Mayor of Liverpool, the painter Augustus John and one woman, my grandfathers academic assistant Dora Yates.

As one journalist described the scene:

On an open space in the street was a motley crew indeed. Farm hands in quaintly-cut corduroys, the representatives of Romany, rich and poor, ladies in fur coats, and gentlemen in plus fours. Seated at a harp was a dark, flashing-eyed gipsy maiden, twanging a plaintive melody, the while a white-haired member of the same tribe accompanied on the fiddle. Gipsies greeted each other in their own language, and kissed in the true gipsy fashion. It was a most picturesque scene the male gipsies in their red bandana kerchiefs, and the fairer sex in colourful but tattered dresses, and hair bedecked with spangles and coins. Hundreds of spectators looked on and waited waited for the coming of the last mortal remains of Dr John Sampson, the well known philologist and librarian of Liverpool University.

The odd party processed slowly up the mountain, led by the gypsy Ithal Lee bearing the casket of ashes and followed by gypsy musicians with harps, fiddles, clarinet and dulcimer. Among the musicians were three descendants of the great harpist John Roberts of Newtown his son with a harp, his grandson with a violin and his great-grandson with a flute. Then came my father looking stiff and ill at ease, and Augustus John rather Gypsy-like in his full grey beard and his scarlet-spotted scarf.

Eventually they reached a plateau of level grass just below the summit of the mountain. The sun shone in a clear blue sky and beneath them lay the Welsh valley, with the Snowdon range visible on the horizon. Augustus John stood bareheaded in the centre his eyes fixed on the distance, a smouldering cigarette in his hand and proclaimed in a powerful voice:

Obeying his last wishes, we, his friends, bear hither the ashes of JOHN SAMPSON in order that, scattered over the slopes of this beautiful mountain, they may become part of the land he loved and rest near the remnant of the ancient race for whom he lived. We build no monument, we inscribe no stone to bear his name. Long will he live in our hearts: longer still in the great work he has done. Mourn we must that never again can we take by the hand the most faithful of friends; yet we rejoice that he was sent among us to be our companion in sorrow and in joy, to protect from decay our old traditions, and to enrich the worlds store of learning.

Ithal Lee held out the casket to my father who took the ashes and scattered them nine times over the mountainside. The mourners recited the Romani words for earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust. One Welsh spectator was heard to exclaim: Pity tis to scatter the ashes so, and give the Almighty all the work of collecting them together again. Then Augustus John stretched out his right arm and recited Romani verses that the Rai had written thirty years before.

Scholar Gypsy, Brother, Student,

Peacefully I kiss thy forehead,

Quietly I depart and leave

Thee whom I loved Good night...

Across deaths dark stream

I give thee my hand; and what

Thou wouldst have desired for thyself

I wish thee: Mayst thou sleep well.

The mourners raised their hands and repeated the Romani blessing: te soves misto mayst thou sleep well and Reuben Roberts played on the heavy triple harp the Rais favourite tune, the Welsh lament David of the White Rock. Harpists and fiddlers joined in with other tunes. Ithal Lee broke up the casket and burnt it to cinders burning the property of the dead in gypsy style and then quietly lit his pipe from the blaze. Some mourners thought this irreverent but Ithal had always insisted that in his heart the Rai was a gypsy; and later he confided: I knew the Rai would have said to me, Arent you going to light up, Ithal? you see I hadnt had a smoke all morning.

Then the mourners and musicians turned away and walked slowly down to Llangwm. Tears were rolling down Augustuss cheeks, but the gypsies insisted that weeping and laments would disturb the rest of the dead.

Later, the gypsies, scholars and friends all reassembled for a funeral feast, complete with the best wines and cigars, a few miles away at The White Lion in the hilltop town of Cerig-y-Drudion. Marguerite Owen, the licensee, could not recall such a sumptuous feast: We have made great preparations such as we have never made before, nor any of our predecessors.

The funeral was front-page news on the following Monday. The Daily Mirror made it their lead story GIPSY RITES FOR ROMANY SCHOLAR with photographs of a gypsy fiddler, my father scattering the ashes, and the mourners walking up the mountain. The