SHADOW OF THE BEAR

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Hail Mary Corner

SHADOW OF THE BEAR

Travels in Vanishing Wilderness

Brian Payton

BLOOMSBURY

Copyright 2006 by Brian Payton

Illustrations 2006 by Peter Karsten

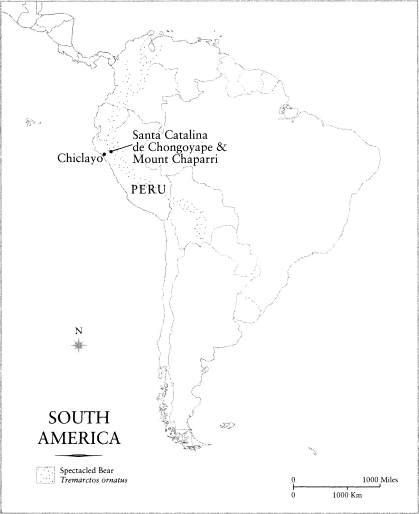

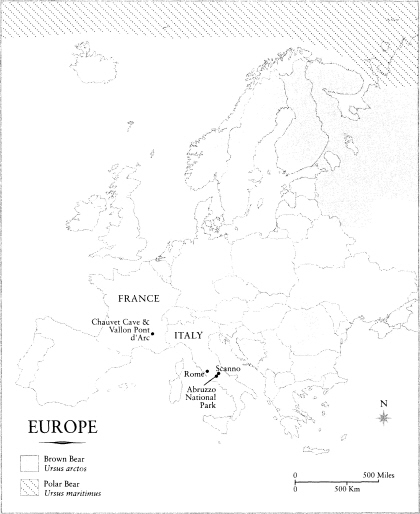

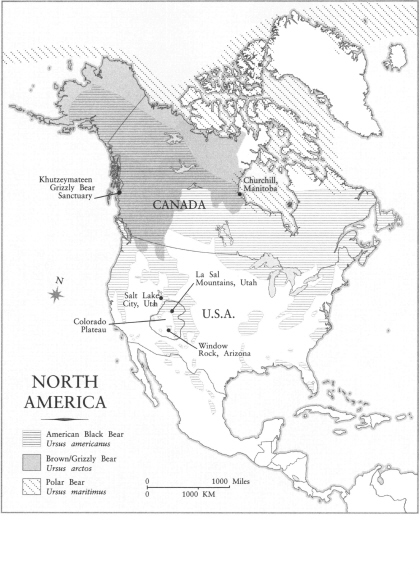

Maps 2006 by James Sinclair

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case o{ brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, address Bloomsbury Publishing, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Published by Bloomsbury Publishing, New York and London

Distributed to the trade by Holtzbrinck Publishers

All papers used by Bloomsbury Publishing are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in well-managed forests. The manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

This is a work of nonfiction. All of the events and conversations contained herein actually occurred. In a few instances, names were changed to protect sources.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Payton, Brian.

Shadow of the bear : travels in vanishing wilderness / by Brian Payton.

1st U.S. ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-1-59691-875-7

1. Bears. 2. Endangered species. 3. Human-animal relationships. I. Title.

QL737.C27P364 2006

599.78dc22

2005032031

Portions of the introduction appeared in a different form in

Canadian Geographic.

First U.S. Edition 2006

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset by Westchester Book Group

Printed in the United States of America by Quebecor World Fairfield

For Lily

CONTENTS

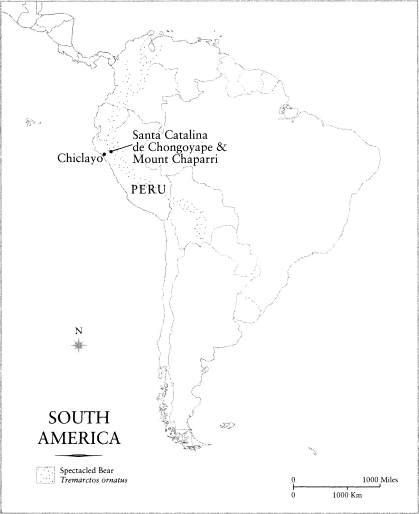

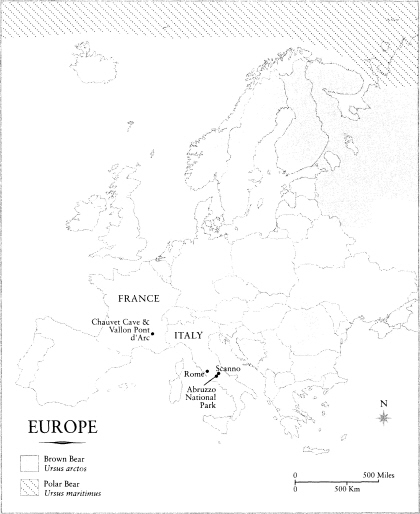

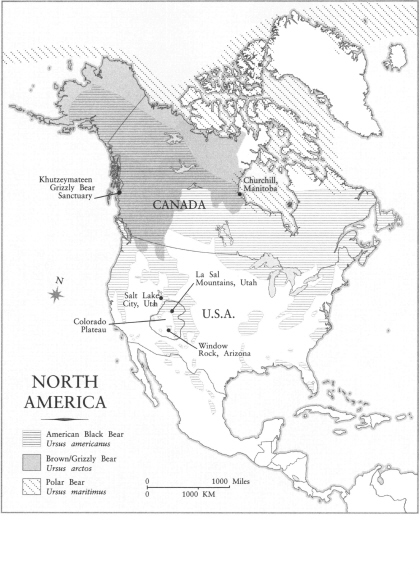

Maps

INTRODUCTION

A Sleuth of Bears

THERE ARE MOMENTS of clarity in life, instances that so completely focus the senses, there is no yesterday or tomorrowonly the absolute here and now. Such a moment came for me in the spring of 2000, on the coast of British Columbia, when my guide reached for the oar in the bottom of our boat and accidentally spooked a grizzly cub on shore.

The overgrown three-year-old bawled and temporarily lost his footing. His mother, grazing sedge nearby, spun around and stopped mid-chew. We were so close, I could see the foamy, green saliva at the corners of her mouthso close I could see her eyes focus on me. Several heart-pounding seconds passed as we stared at one another, reading body language, plotting possible outcomes. Then all at once she turned and sat down. Seemingly unconcerned with our presence, she kept her back to us and her cub as she continued munching on stems and blades.

From what I'd gathered about meeting bears in the wilderness, coming upon a mother and cub seemed like the worst-case scenario. And yet somehow these bears put me at ease. Convinced he'd established who was in charge, the cub scrambled up a large rock for a better view. He yawned, licked his paws, and even dozed off for a while. He resembled a young royal, aware of the flashing cameras but intent on maintaining the pretense of normalcy.

A few minutes later, the pair slowly ambled away from the water's edge and disappeared into the forest.

WE' VE BEEN MEETING them in the wilderness, and in our dreams, since the dawn of human history. Bears have been celebrated in art and myth since we began drawing on the walls of caves. No beast casts a longer shadow over our collective subconscious. Perhaps more than any other animal, the bear remains at the very heart of our concept of wilderness.

The hope of seeing grizzlies in their natural habitat brought me and six companions to the mouth of the Khutzeymateen (KOOT-suh-mah-teen) River in Canada's only grizzly bear sanctuary. The inlet reaches twelve miles in from Chatham Sound, forming an arm of the Pacific Ocean that ends in fingers full of rich green sedge. After emerging from hibernation, grizzlies make their way down to the marsh to feast on the bounty of new shoots that offer up to 28 percent protein. A place of plenty, the marsh attracts dozens of bears each spring. After establishing a pecking order, these ordinarily solitary creatures graze in close proximity. This gathering, known as a sleuth of bears, is something that rarely happens in the wild.

I was determined to get up close and experience being in a place where humans are not the masters of all we seea place where we are at least one link down the food chain. For four days, guide Tom Ellison's seventy-two-foot ketch served as our mother ship for exploration. Anchored in a sheltered cove, we were surrounded by slopes of old-growth cedar and snowy peaks soaring nearly seven thousand feet above the tide. Himself an imposing figure, Ellison's weathered features betrayed a long association with the wilderness and the sea. He knew these bears better than anyone.

We wandered the rainforest in heavy downpours and soft, persistent mist. More than nine feet of precipitation soaks this part of the coast each year and the resulting jungle is dark and primeval. Grizzly bears play an integral role in this environment, consuming huge quantities of salmon and conveying valuable nitrogen fertilizer deep into the forest. They are the unwitting gardeners of some of the world's oldest, biggest trees. In North America, before the advent of industrial logging, temperate rainforests once stretched along the West Coast from California's giant sequoias to Alaska's majestic Sitka spruce. Among the world's rarest ecosystems, temperate rainforests never covered more than one-fifth of i percent of the planet's land surface. Today, less than one-half of that small amount remains.

On one of our forest walks, we found a bear trail below an old hemlock tree. Unlike other animal or human paths, where an unbroken line is traced on the earth, here each bear carefully placed its paws in exactly the same spot as the bears that passed before it. The result was a series of round, measured paw pads in the bright green moss. Some speculate that these trails are ancient pathways, trod by untold generations. Passing bears have also left their marks on nearby scratch trees, which provide temporary relief from an itchy back and serve as a kind of social register with scent, bits of fur, and claw marks that let other bears know who's in the neighborhood.

I was fully aware that these bears could tear me apart. Although the vast majority of encounters between people and bears are peaceful in this part of the world, every couple of years someone gets killed. However, within this protected, pristine environment, bears have not learned to fear humans or associate us with handouts or garbage. Here, it is possible to meet them on unencumbered terms.

I discovered that the same government that protects the sixty grizzlies in this estuary sanctions the killing of approximately three hundred others in British Columbia's annual grizzly bear hunt. It is estimated that another three hundred are victims of poaching. A considerable number of these are killed only for their gallbladders, which end up as medicine in Asian apothecaries, or for their paws, which are served as exotic delicacies in restaurants around the world. Despite the numbers directly killed by humans, it is believed that habitat destruction remains the most serious threat to the survival of these and most other bears.

Next page