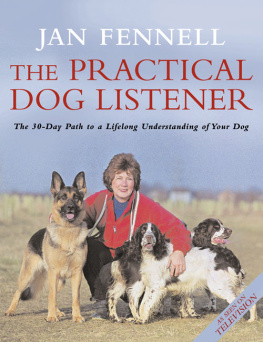

JAN FENNELL is the author of two previous books. The Dog Listener was a comprehensive introduction to her methods, and it remained at number one for eight weeks, becoming indispensable to dog lovers and animal trainers everywhere. The Practical Dog Listener was the best-selling follow up which promised to turn around the behaviour of even the most troublesome dogs within thirty days. Jan lives in rural Lincolnshire.

Australia

HarperCollins Publishers Australia Pty. Ltd.

Level 13, 201 Elizabeth Street

Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia

www.harpercollins.com.au

Canada

HarperCollins Canada

Bay Adelaide Centre, East Tower

22 Adelaide Street West, 41st Floor

Toronto, Ontario M5H 4E3, Canada

www.harpercollins.ca

India

HarperCollins India

A75, Sector 57

Noida, Uttar Pradesh 201 301, India

www.harpercollins.co.in

New Zealand

HarperCollins Publishers (New Zealand) Limited

P.O. Box 1

Auckland, New Zealand

www.harpercollins.co.nz

United Kingdom

HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF, UK

www.harpercollins.co.uk

United States

HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

195 Broadway

New York, NY 10007

www.harpercollins.com

I thought that this would be the most difficult book to write, but putting my life into words helped me to find many answers. I know now how vital every event proved to be on my journey to become The Dog Listener.

Firstly, I would like to thank the Teams at Gillon Aitken and HarperCollins for their belief in me; especially my agent Mary Pachnos, who has been there for me every step of the way. She has become very dear to me.

More than ever I wish to acknowledge those who support me on a day to day basis. My partner Glenn Miller, who works tirelessly behind the scenes. Alison Powrie and my son Tony Knight who so proudly carry on my work world-wide, and Charlotte Medley who helps care for our wonderful pack. My family and friend who are always there for me. Together we have a lot of fun.

Jan F

The Dog Listener: Learning the Language of your Best Friend

The Practical Dog Listener: The 30-Day Path to a Lifelong Understanding of Your Dog

A Dogs Best Friend: The Secrets that Make Good Dog Owners Great

The Seven Ages of Your Dog

The Puppy Listener

I was born of a loving relationship. The only problem was that where my mother and father were concerned, they reserved most of that love for each other. I was the only child, the little nuisance who got in the way, the living embodiment of the old saying that twos company but threes a crowd. I often think I spent my childhood as an outsider looking in on their private happiness. I bear no resentment towards my parents. I have tried to understand how hard life was for them, and to a large degree I have succeeded. If I am brutally honest, however, there are still times when I ask myself why they bothered having me.

Until I came along, their story could have come straight off the pages of a slushy romantic novel. My mother, Nona Whitton, met my father, Wally Fennell, in London a year after the end of World War II, in 1946. It was a time of hardships, and the war still cast a long shadow over life in England.

My dads war seemed like something out of Spike Milligans madcap accounts of life in the Army. Dad always said war was a joke and his experiences proved it. During his six years in the Army he was charged with desertion by one regiment when he was already fighting with another one altogether and reported dead when he was still very much alive.

The desertion charge was laid by the Royal Engineers, his second regiment, who called him up in 1941, two years into the war. They charged him when he failed to reply to his call-up papers, then discovered to their embarrassment that he had volunteered to serve with the Gloucesters when the war had first broken out.

Dad was a practical man and his talents suited the Royal Engineers. He was often sent behind enemy lines to prepare the way for the fighting divisions and it was during a mission somewhere in Europe, in 1943, that he was reported missing in action. The telegram that broke the news had a terrible effect on his father, George Fennell, who had already lost three of his six sons in tragic circumstances. The news that another was missing presumed dead was too much to bear. He died of a heart attack days later. My father never really forgave the Army for that; he had not been killed or captured at all and he turned up safe and well just in time to travel back to England for his fathers funeral. What a happy homecoming that was for him.

My dad always believed in what he was fighting for, in serving King and Country. But he also believed war was a series of mishaps. Anybody whose job is to blow things up and then put them back together again doesnt feel very constructive in a war, he used to say. His philosophy seemed to have been that if you didnt laugh youd go mad.

His nickname in the Army was Crash because of all the scrapes he got himself into. He was obviously a good soldier, being busted as a sergeant, that is to say promoted then demoted again, seven times. His final promotion came in the field and was given by a Canadian officer who saw that my father was the one organizing everything. The officers didnt know what they were doing, according to my father; it was up to the ordinary enlisted men to sort out the mess the officers made.

The low point of my fathers war came at Arnhem. His unit was moving forward with an escort of tanks into an area just recaptured from the Germans. They had been told the area was free of enemy troops and had been sent ahead to clear the path. No sooner had they set off than the German tanks came over the hill again and my dad was fleeing for cover.

It was a close-run thing, shells going off all over the place, men falling to the ground. Most of Dads unit made it but when they reached safety in the trees someone said: Crash, look at your knee. It was in bits. He had also badly damaged his elbow. But it wasnt the end of his war. The Army surgeons put his knee back together with a piece of silver wire. He went back to Europe and stayed on with the Royal Engineers, building bridges in post-war Holland until early 1946.

My father had been twenty-one when he left home. Six years later he returned from the war with a bad limp and the feeling that he had sacrificed his youth, his health and probably his chances of happiness. He often said the war took the best years of his life.

My mother, on the other hand, looked back on the war with feelings of nostalgia. I think the period between 1939 and 1945 provided her with the best time she ever had. For her life afterwards was an anticlimax.

Like my father, she was from west London. Without knowing the full details until much later I was aware that her childhood and teenage years had been tough. Her father had died relatively young, when her mother was expecting the fourth of their children. So when war broke out my mother, like many other young women, found it a liberating experience. She had a job working in a munitions factory, earned a good income and suddenly found herself part of a group of independent girlfriends who were determined to live every day and night as if it were their last which in the London of the Blitz it might easily have been.

For Mum life was made all the more exciting by the fact that, at twenty, she was a really beautiful-looking girl. We never talked about that period much, for deeper reasons that would eventually reveal themselves. But I think she was engaged seven times. The one story Mum would recall, ad flippin nauseam, was of the New Years Eve party when Stewart Granger danced with her.