A wonderful book about the opposite of remaining static

Giles Foden, i Newspaper

An epic journey and a book worthy of it An important new voice has arrived

Charles Foster, author of Being a Beast

[Martineau] is fine and thoughtful company for the journey, sensitive to the fraught history of Europeans who have used Africa and Africans as a backdrop for their exploits

Washington Post

A story of tenacity, told with humility, in a West Africa experienced deeply at the pace of a walk. I loved this book

Sophy Roberts, author of The Lost Pianos of Siberia

The evocative, delicate writing leaves you feeling the very ground under his feet as Martineau makes his way on this most astonishing pilgrimage

Adharanand Finn, author of Running with the Kenyans

Terrific A travel-writing gem

Tim Butcher, author of Blood River

Martineau weaves together philosophy history and glorious descriptions of the landscape, all the while demonstrating the power of walking to heal mental wounds

Tatler

A magnificent book Waypoints is a paean to the transformative power of a long journey on foot

Ben Saunders

A deeply affecting book which sears itself on the memory

Philip Marsden, author of Rising Ground

As soon as I picked Waypoints up, I couldnt stop reading immediate and soulful and searching

Pico Iyer

Waypoints is an insightful, personal and genuinely moving account of what can be achieved with two feet, a backpack and a desire to keep on going An exceptional debut

Vybarr Cregan-Reid, author of Footnotes

Many people struggle with whats going on between their ears but [Martineau has] found a simple solution: get walking

Daily Mail

In the spirit of Bruce Chatwin and Rebecca Solnit Elegant, searingly honest

David Farrier, author of Footprints

His touch is light, his brushwork vivid A poignant illustration of the random kindness of strangers

Michela Wrong, author of Do Not Disturb

An engaging meditation on life and walking and a fascinating glimpse into Martineaus interior journey

Travel Writing World

Robert Martineau

WAYPOINTS

A Journey on Foot

VINTAGE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

New Zealand | India | South Africa

Vintage is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published in Vintage in 2022

First published in hardback by Jonathan Cape in 2021

Copyright Robert Martineau 2021

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover Illustration Keith Hau

Extract from The Wayfinders: Why Ancient Wisdom Matters in the Modern World, copyright 2009 Wade Davis. Reproduced with permission from House of Anansi Press Inc.

Extract from The Dream Songs, copyright 1969 John Berryman. Reproduced with permission from Faber & Faber Ltd

Extract from Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, copyright 1990 Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. Reproduced with permission from Penguin Random House.

ISBN: 978-1-473-56295-0

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Prologue

Most days that August, the August I started writing again, I went to the hospital. I watched the person I was visiting someone I loved slowly come back, day by day, to the person I knew. I watched, through the thin window of those visiting hours, a struggle I found hard to understand.

Id come in the ambulance on the first day. Neither of us had slept the night before, him perhaps not for three or four days. Walking from the ward the first time, into the grey Acton light, I felt the adrenaline ebb away, then numbness: fear of the uncertainty ahead. Over the following month, that fear slowly faded: I grew somewhat familiar with the hospital; with the routines of ward life; the door-lock system and the sign-in protocols; the patients who smoked on the benches at the entrance; the community of visitors, nurses, and the policemen who each afternoon, it seemed, arrived to drop back a missing patient. I came, over that short period too, to begin to know some of the patients: the man with scars on his neck, who avoided eye contact and had a sharpness in his movements which unnerved the others; the older men, who had dishevelled hair and never changed from their pyjamas, who seemed to endlessly walk the corridors in search of a door that wasnt there; and the young men on the ward for the first time, who were adjusting to the new reality around them, like waking up in a new world.

Some days a volunteer accompanied one of the patients on a walk. I passed her once as I ran home from the hospital, under the bridge where a street of the grim, light industrial buildings that dominate that part of Park Royal meets the towpath of the Grand Union Canal. The first time I saw them return to the hospital from their walk, walking and smiling, I welled up. It struck me that what she was providing a walk, company might be as powerful as the lithium.

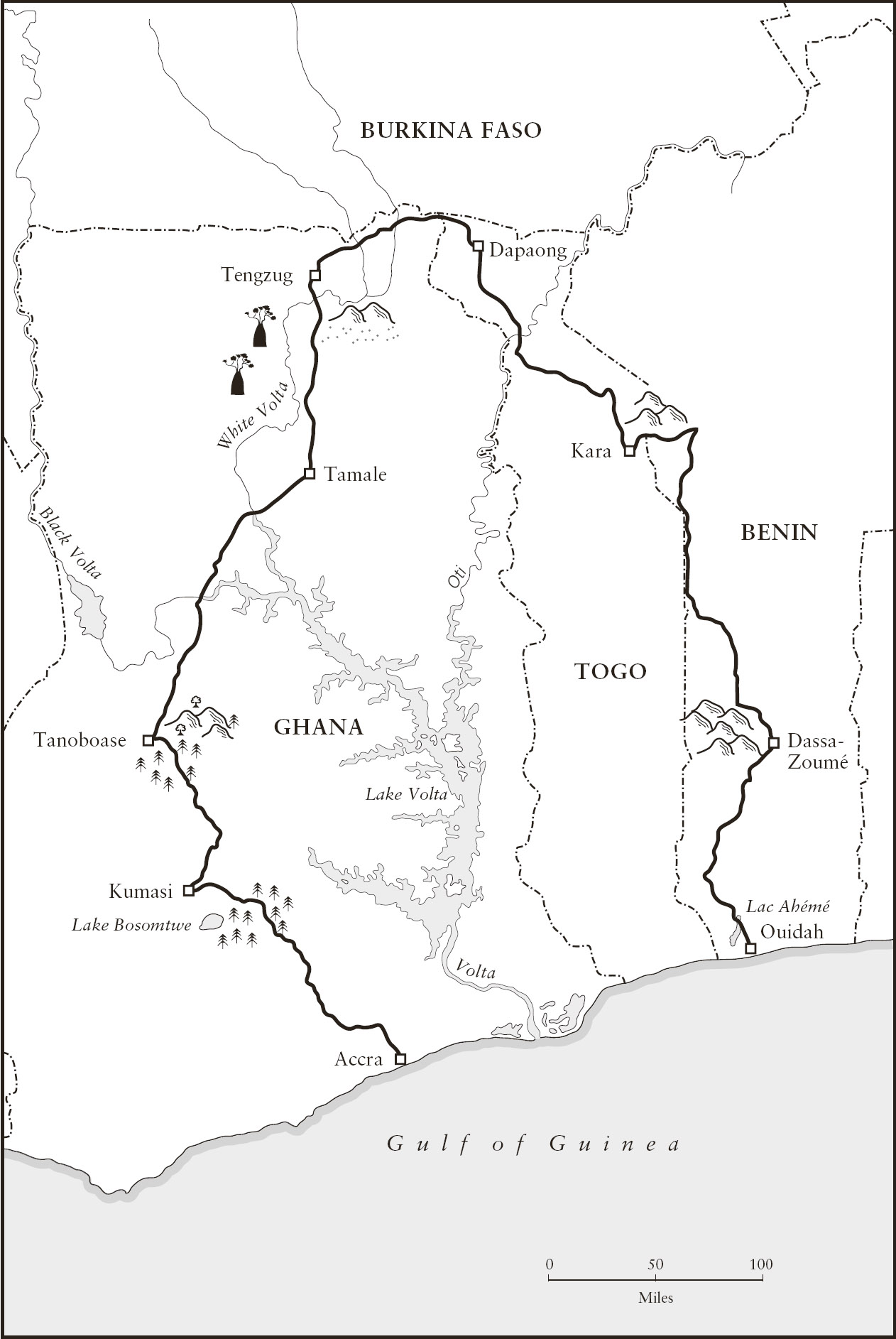

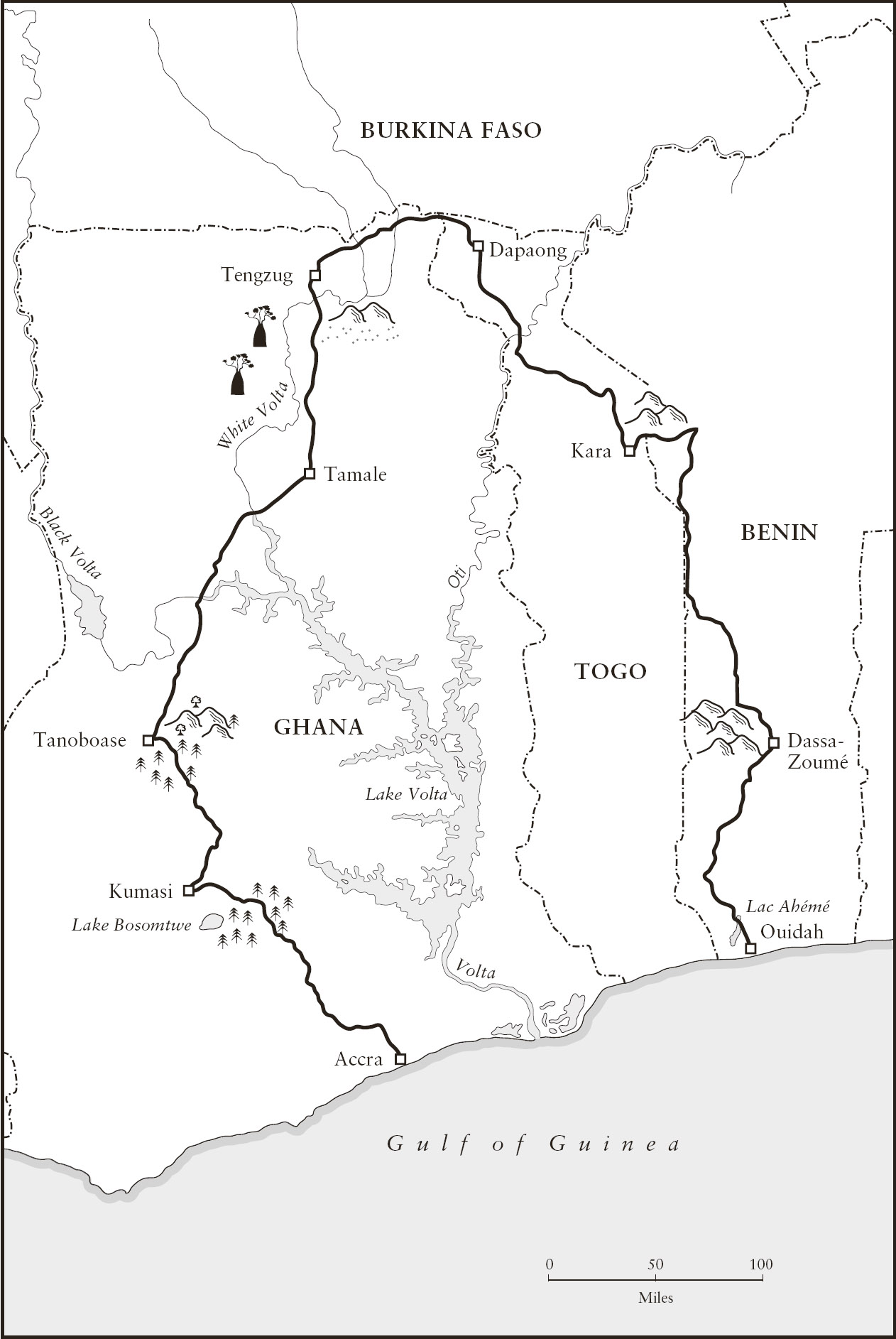

Part of me believed that already. Id spent, four years earlier, six months walking in West Africa. I was twenty-seven then. Id left my job and bought a flight to Accra. I walked a thousand miles from Accra, through Ghana, Togo and Benin, to Ouidah, on the Beninese coast. Id been unhappy before I left, and I saw the walk as a way to fill a void. I imagined walking for months would clear out habits and feelings that weighed me down. I hoped it would work like a fast. I hoped it would bring closure to things long unresolved.

Starting out, the road was a shock. I wasnt prepared for the weight of my pack, for the humidity, for what it would be like to walk for ten, twelve, sometimes sixteen hours a day. During the first days, walking in the forests north of Accra, my body seemed to break down. I sweated so much my eyes stung and my face went white with salt. I threw up every few hours. I remember feeling Id made a terrible mistake, that I wouldnt make it. Gradually my body adapted. It took longer for my mind: to get used to being alone for such long stretches; to being outside all of the time; to having nothing to do but walk, nowhere to go but the path ahead.

Id started writing during those first days walking: each night when I came off the road, I sat in the guest house yard or at the end of my tent, writing by the light from my headtorch. Each month I posted a notebook home. When I got back, there was a small pile of them on my bed. For a while after, I tried to build a story from those notebooks. But I couldnt find a way to communicate what I wanted. I gave up. Besides, the world didnt need another adventure story by a white guy in Africa. At least, thats how I saw it.

Next page