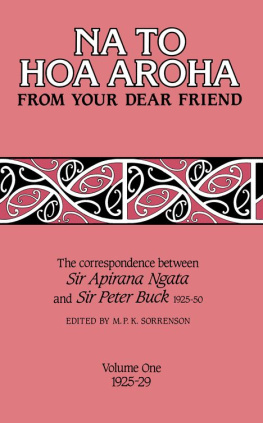

Sir Apirana Ngata (editor) - Na to Hoa Aroha, from Your Dear Friend

Here you can read online Sir Apirana Ngata (editor) - Na to Hoa Aroha, from Your Dear Friend full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2011, publisher: Auckland University Press, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Na to Hoa Aroha, from Your Dear Friend

- Author:

- Publisher:Auckland University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2011

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Na to Hoa Aroha, from Your Dear Friend: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Na to Hoa Aroha, from Your Dear Friend" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Na to Hoa Aroha, from Your Dear Friend — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Na to Hoa Aroha, from Your Dear Friend" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

FROM YOUR DEAR FRIEND

Volume One 192529

TO THE PEOPLE OF TaiRawhiti AND TaiHauauru WHOSE TWO MOST FAMOUS SONS MADE THIS BOOK POSSIBLE

The correspondence between Sir Apirana Ngata and Sir Peter Buck will be completed in three volumes, published at intervals. Volume two will include letters dated from 4 May 1930 to 12 August 1932; volume three from 15 August 1932 to 5 March 1950. Volume three will also include an epilogue and an index to all three volumes.

The publishers gratefully acknowledge assistance towards publication from the Alexander Turnbull Library Endowment Trust and the Maori Purposes Fund Board. Royalties will be paid to the Maori Education Foundation.

A PIRANA NGATA AND PETER BUCK (TE RANGIHIROA) were the most notable Maoris of their time. Graduates of Te Aute College and New Zealand universities, politicians and scholars, they played a unique role in New Zealand history in the first half of the twentieth century. By 1925, when this correspondence begins, both men were in their middle age Ngata was fifty-one and Buck forty-eight and could look back on distinguished careers in politics and public administration. With other members of the Young Maori Party, they had contributed much to the rehabilitation of the Maori people, Ngata more especially in land reform, Buck in health. At a time in life when most men slow down and begin to contemplate retirement, Buck and Ngata were about to embark on the most strenuous and significant phases of their careers. In 1927 Buck resigned as Director of Maori Hygiene in the Department of Health to take a Research Fellowship with the Bishop Museum in Hawaii, thus beginning a career as a professional anthropologist that would take him to the directorship of the museum and the status of a chair at Yale University. In 1928 Ngata became Native Minister in Sir Joseph Wards United administration a position for which he had long been preparing himself and began a hectic programme of land development and cultural regeneration of the Maori people.

The letters that follow detail Ngatas and Bucks achievements, at home and abroad. But they are much more than that; for they are also a record of ideas and ideals, of hopes and, occasionally, fears for the Maori people. The correspondence provides a revealing account of the continuing importance of kinship in Maori society, of whanau, hapu, and tribe, and of the state of race relations between Maori and Pakeha. And with Bucks researches and travel through the Pacific, there are comments on other Polynesians Cook Islanders, Samoans, Hawaiians and the inevitable comparisons between them and Maoris, invariably to the advantage of the latter. If Ngatas taumata or vantage point from which he viewed the human landscape was always Hikurangi, the mountain of his Ngatiporou tribe, Bucks had moved from Taranaki to Maunaloa, the volcanic peak in Omahu, Hawaii, which allowed him to gaze over the Pacific from the northern apex of the Polynesian triangle. From those twin peaks we get an intellectual exchange of unparalleled significance. For the correspondence is in many ways a history of New Zealand and Pacific anthropology for the 1920s and 1930s. In this respect Ngata and Buck believed that they had a supreme advantage over Pakeha colleagues their Maori ancestry and upbringing which enabled them to understand Maori psychology, the ngakau Maori, the inner feelings and emotions of their people. It was this conceit which gave Buck and Ngata, in their middle age, the confidence to confront a potentially critical anthropology profession.

In the correspondence Ngata and Buck are frequently retrospective; they pick out people, places, and events that they see as major influences in their lives. They were concerned about their standing with their contemporaries and in history; and after some years the letters were being written with an eye to preservation and possibly publication. Extracts from them were published in scholarly articles, official papers, or the press. Buck made several attempts to start an autobiography but never got beyond a few pages and handed over the task to the journalist, Eric Ramsden, who used the correspondence for a draft of a biography. This was subsequently rewritten and published by Professor J. B. Condliffe, the economist and historian, a long-standing friend and colleague of Bucks. Ramsden also hoped to write Ngatas biography and did publish a small commemorative volume in 1948 to mark Ngatas honorary doctorate, but Ngata was never keen on handing over his life and papers to a Pakeha scribe believing that these things should remain with the family.

From these and other sketches, are tolerably well known. Yet something must be said about their early careers to provide background to the correspondence. Many of the ideas and policies that were to bear fruit in the period of the correspondence had been conceived and tried out experimentally before the First World War, even, in some cases, before the turn of the century. Ngata and Buck had been close friends for thirty years before the correspondence began and their careers were remarkably similar: Buck followed Ngata through secondary school and university (though they did different degrees) and, after briefly practising, also followed him into parliament. But there were also significant differences of birth, upbringing, and temperament which need to be noticed.

Apirana Turupa Ngata was born on 3 July 1874 at Te Araroa on the East Coast. His whakapapa

Ropata and Paratene had followed this policy through the last three decades of the century; it was to be the task of the young Apirana, with his Pakeha education and skills, to carry it on more effectively in the next generation. He began that education at five when he went to Waiomatatini Native School, one of the village schools established under the Education Act of 1867 with active support from Ropata and Paratene. After only four years Ngata went on, with a Makarini scholarship, to Te Aute, the Anglican boarding school for Maori boys in Hawkes Bay.

Buck was to follow Ngata to Te Aute but by a rather more tortuous path. In contrast to Ngata, Bucks early years were obscure and insecure. The precise date of his birth is uncertain Buck himself never knew it and often said he was born in 1880 but it is more likely to have been October 1877, which was the date recorded in his primary school register. crippled, she treated him with much affection and introduced him to some of the language and lore of her people.

The situation of Bucks Taranaki kin was very different from that of Ngatas Ngatiporou, for Ngati-Mutunga had fought against the Pakeha in the wars of the 1860s and lost most of their land by confiscation. Since the wars the Taranaki Maoris had placed their trust in the prophet Te Whiti o Rongomai who, from Parihaka in south Taranaki, led the resistance to the occupation of the confiscated Waimate plains. As he grew up Peter realized that Te Whiti was espousing a lost cause. In north Taranaki the Maori situation was even more hopeless since the confiscated land had already been occupied by military settlers. Peters father had gone to Urenui as part of the Armed Constabulary; even though he had taken his discharge, he could still be called into service against the Maoris in the event of an emergency. So Peter grew up poised rather uneasily between his Maori and Pakeha kin. The Bucks house was just across the river from the Pakeha village of Urenui, but Peter went to Urenui Primary School, a state rather than a Native school. Most of the pupils were Pakeha but Buck kept up some Maori affiliations it was at this time that he adopted the name he was frequently to use as a pen name, Te Rangihiroa, after Ngarongos uncle. Peter passed the sixth standard, but after the death of Ngarongo, his father moved him away from his Maori kin in some secrecy. They went to Wellington, then to the Andrews station in the Wairarapa. It was from here, with encouragement from Andrews, that Buck applied for Te Aute, being admitted in 1896. It is tempting to dismiss W. H. Buck as a rouseabout and to contrast him unfavourably with Paratene Ngata but he did have some useful influence on Peter who many years later acknowledged that he had derived his love of language and poetry from his father.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Na to Hoa Aroha, from Your Dear Friend»

Look at similar books to Na to Hoa Aroha, from Your Dear Friend. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Na to Hoa Aroha, from Your Dear Friend and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.