#1 It Doesnt Suck.

Showgirls

#2 Raise Some Shell.

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles

#3 Wrapped in Plastic.

Twin Peaks

#4 Elvis Is King.

Costellos My Aim Is True

#5 National Treasure.

Nicolas Cage

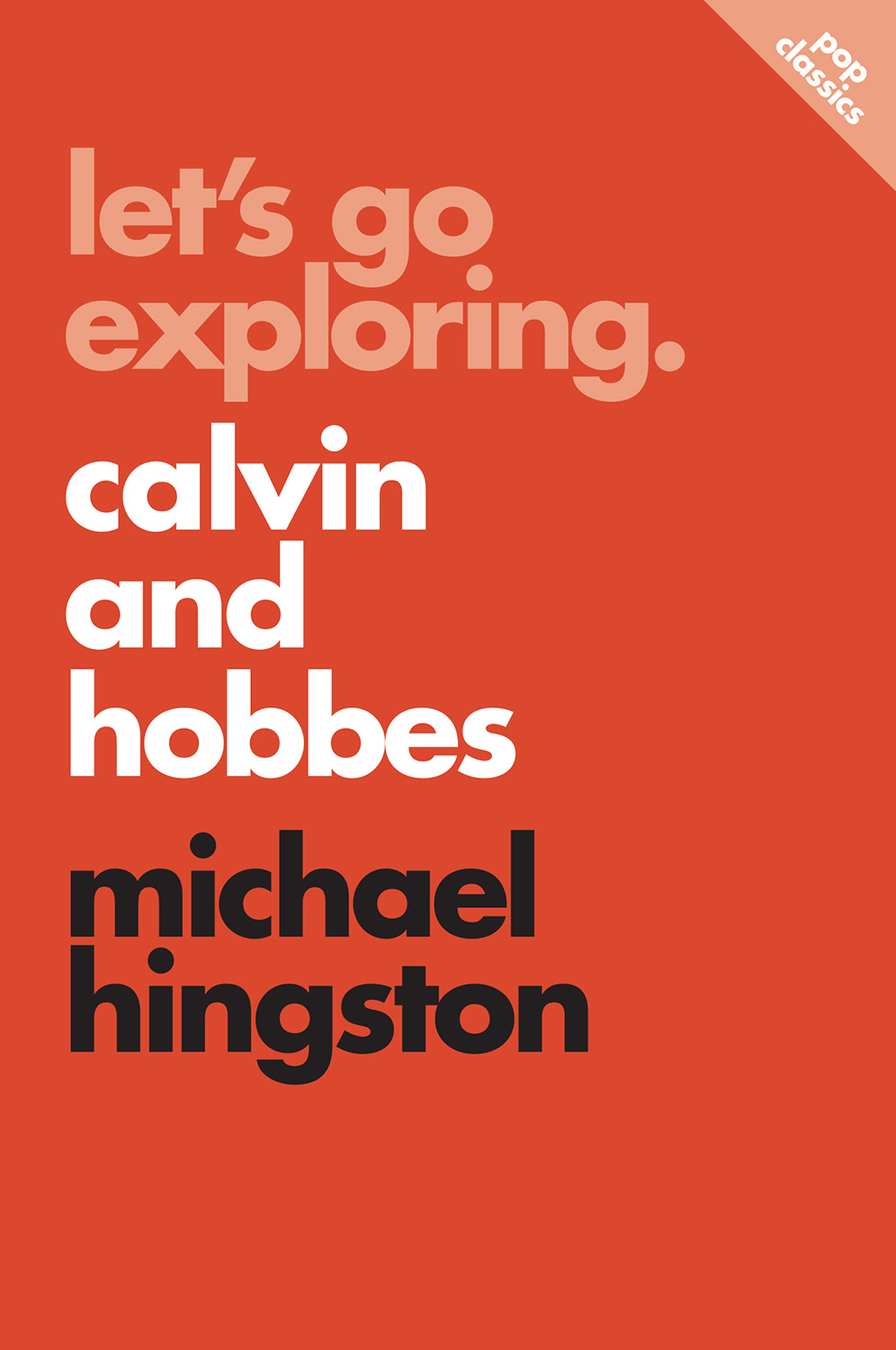

#6 In My Humble Opinion.

My So-Called Life

#7 Gentlemen of the Shade.

My Own Private Idaho

#8 Aint No Place for a Hero.

Borderlands

#9 Most Dramatic Ever.

The Bachelor

#10 Let's Go Exploring.

Calvin & Hobbes

You cant please all the people all the time.

Nowhere is that free-floating internet maxim truer than when it comes to a work of art, with its baked-in subjectivity, its reliance on context and historical precedent, and its right-brained appeal to emotion and the senses. Storytelling itself is as old as it is diverse, with a palette containing everything from Homeric ballads to hashtag rap. Illustration is an equally tricky beast, capable of turning viewers off with something as innocent as the thickness of the artists pen stroke. Mediums aside, creators must also stick their projects flag somewhere on the continuum between realism and abstraction, each with their attendant fans and detractors. And if, on top of all that, your art is meant to be funny? God help you. Most of the time, a joke broad enough for everyone to understand is by definition too bland for anyone whose taste veers toward the deep end of a particular niche or genre and thats when the joke is successful. A vague, failed stab at comedy might be the most painful outcome of all.

And yet, even in our world of jumbled, almost hopelessly opposing tastes, sometimes the stars do align. Sometimes, you wind up with a comic strip like Calvin and Hobbes.

Created by Bill Watterson, and making its newspaper debut in 1985, Calvin and Hobbes is the story of a six-year-old boy and the stuffed tiger that, in Calvins eyes, becomes his real-life (and occasionally feral) best friend. The strip is a blend of casual intelligence, rich characterization, visual panache, and noble goofery, and it ran in thousands of papers across North America from 1985 until its abrupt retirement ten years later. Since then, the strip has lived on in tens of millions of books, in dozens of different languages, all around the world. But most impressive of all is the fact that almost nobody seems to actively dislike it.

Ive never met anyone who doesnt like Calvin and Hobbes, Jenny Robb, curator of the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum, once said. And I cant say that about any other strip. During its run, Calvin and Hobbes quickly established itself as both a critical and commercial juggernaut. It won seven consecutive Harvey Awards for Best Syndicated Comic Strip, and by 1988, Watterson had become the youngest cartoonist, at age 30, to win the prestigious Reuben Award twice. Meanwhile, the strip routinely topped newspaper readers polls, and its annual book collections each enjoyed first printings that ran into the seven figures. Even when you take this query to the internet at large, where hatred for any conceivable topic is always just a few keystrokes away, the lovefest continues. Aside from a single newspaper cartoonist who in the 90s once said that he never bought Wattersons premise, the closest I came was Google suggesting some alternate search terms. Did I perhaps mean calvin and hobbes i hate when my boogers freeze? (No, but now that you mention it...)

So how did Watterson do it? The secret to the strips appeal was that it had multiple appeals. Watterson infused Calvin and Hobbes with a winning mix of high-minded philosophy and gross-out humor from the very beginning. One strip might feature Calvin looking to the sky, solemnly mulling over the meaning of life; in the next, hes wrestling a sentient bowl of oatmeal. Meanwhile, Hobbes named after the 17th-century philosopher who had, as Watterson put it, a dim view of human nature was as likely to serve as the rational check on Calvins harebrained schemes as he was the animal id, ready to pounce on his best friend the moment he got home from school. Watterson wasnt afraid to name-drop obscure French painters, or to write multi-day stories in which the majority of the characters are dinosaurs. And present in all of his work was a seemingly limitless sense of creativity. Watterson walked the line between reality and fantasy with uncommon agility, and he took even greater delight in smooshing the two realms together, showing all the ways his six-year-old hero could use his imagination as a refuge from a real world that was too oppressive, too literal-minded, and too flat-out boring to be tolerated for any significant length of time.

Calvin won readers over because he remains one of the most perfectly distilled visions of childhood ever committed to paper: rude, petulant, screamingly funny, gross, wise beyond his years, and utterly oblivious sometimes all at the same time. In a strip about the threat and the promise of growing up, Calvin was our Peter Pan, allowed to remain young forever while we were forced away into the rank and file of adulthood. And his creators decision to avoid topical references has allowed Calvin and Hobbes to live on, too, unscathed by the passage of time, as potent now as it ever was. While undeniably a product of his time and place (the American Midwest, circa 19851995), Calvin embodies the enduring nature of what it means to be six years old about as well as any fictional character ever has.

At the same time, Calvins success as a character owes a lot to the larger universe he traveled within. Calvin and Hobbes has a cast of fewer than ten regular characters, and the majority of the strips take place in and around its protagonists house. Yet the strip has enough imaginative firepower to suggest an almost infinite supply of people and ideas hiding around every corner most of which came straight out of Calvins almost uncontrollable imagination. Spaceman Spiff. Tracer Bullet. Stupendous Man. The transmogrifier. Calvinball. These werent mere throwaway gags; rather, they were fully realized strips-within-the-strip, each with its own vocabulary, tone, and even visual style. And when Watterson did decide to reference something outside the world of the strip, it was always with the intention of surprising readers, pushing their curiosity into realms well beyond the funny pages.

Most comics are content to half-heartedly riff on the news stories covered elsewhere in that days paper, but despite the mediums lowbrow reputation or maybe because of it Watterson strove to make his references as lofty as possible, shouting out Paul Gauguin or Karl Marx rather than whatever celebrity was making headlines that week. Even in his vocabulary, Watterson went above and beyond, sprinkling in exotic words and phrases like avant garde, cognoscenti, and hara-kiri. In one strip, Calvin asks Hobbes, What if somebody calls us a pair o pathetic peripatetics?! He adds, Shouldnt we have a ready retort?

Untold numbers of kids, newly galvanized as they read this strip over their morning cereal, banged their spoons on the table in agreement: Shouldnt they?

***

This is the part of the introduction where I neatly pivot into a long, meandering reminiscence about what Calvin and Hobbes