Dorothy L Sayers

Dorothy L Sayers

Oxford-educated Dorothy Leigh Sayers (1893-1957) was one of the most popular authors of the Golden Age era. Born in England in 1893, Dorothy Sayers received her degree at university in medieval literature. Following her graduation, besides publishing two volumes of poetry, she began to write detective stories to earn money.

Her first novel, "Whose Body?" (1923), introduced Lord Peter Wimsey, the character for which she is best known. Wimsey, with his signature monocle and somewhat foppish air, appeared in eleven novels and several short stories. Working with his friend, Inspector Parker of Scotland Yard, Wimsey solved cases usually involving relatives or close friends.

Dorothy L. Sayers was well known for "combining detective writing with expert novelistic writing," and the imaginative ways in which her victims were disposed of. Among the many causes of death seen in her novels were, among others, poisoned teeth fillings, a cat with poisoned claws, and a dagger made of ice! (The Whodunit)

Dorothy Sayers also edited several mystery anthologies collected under the heading "The Omnibus of Crime" (1929), which included a noteworthy opening essay on the history of the mystery genre.

Later on in her life, Dorothy Sayers gave up detective fiction to pursue her other interests. She spent the last years of her life working on an English translation of Dante's Divine Comedy, having always claimed that religion and medieval studies were subjects more worthy of her time than writing detective stories

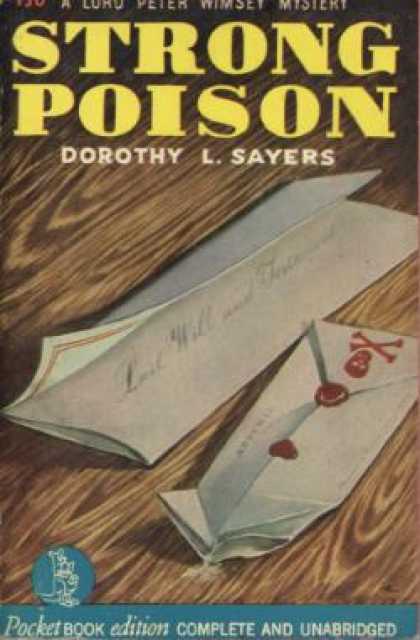

Strong Poison

Dorothy L. Sayers

First Published: (1930)

Table of Contents

Where gat ye your dinner, Lord Rendal, my son?

Where gat ye your dinner, my handsome young man?

O I dined with my sweetheart, Mother; make my bed soon,

For Im sick to the heart and I fain wad lie down.

O that was strong poison, Lord Rendal, my son,

O that was strong poison, my handsome young man,

O yes, I am poisoned, Mother; make my bed soon,

For Im sick to the heart, and I fain wad lie down.

Old Ballad

Chapter I

THERE were crimson roses on the bench; they looked like splashes of blood.

The judge was an old man; so old, he seemed to have outlived time and change and death. His parrot-face and parrot voice were dry, like his old, heavily-veined hands. His scarlet robe clashed harshly with the crimson of the roses. He had sat for three days in the stuffy court, but he showed no sign of fatigue.

He did not look at the prisoner as he gathered his notes into a neat sheaf and turned to address the jury, but the prisoner looked at him. Her eyes, like dark smudges under the heavy square brows, seemed equally without fear and without hope. They waited.

Members of the jury

The patient old eyes seemed to sum them up and take stock of their united intelligence. Three respectable tradesmena tall, argumentative one, a stout, embarrassed one with a drooping moustache, and an unhappy one with a bad cold; a director of a large company, anxious not to waste valuable time; a publican, incongruously cheerful; two youngish men of the artisan class; a nondescript, elderly man, of educated appearance, who might have been anything: an artist with a red beard disguising a weak chin; three womenan elderly spinster, a stout capable woman who kept a sweet-shop, and a harassed wife and mother whose thoughts seemed to be continually straying to her abandoned hearth.

Members of the juryyou have listened with great patience and attention to the evidence in this very distressing case, and it is now my duty to sum up the facts and arguments which have been put before you by the learned Attorney General and by the learned Counsel for the Defence, and to put them in order as clearly as possible, so as to help you in forming your decision.

But first of all, perhaps I ought to say a few words with regard to that decision itself. You know, I am sure, that it is a great principle of English law that every accused person is held to be innocent unless and until he is proved otherwise. It is not necessary for him, or her, to prove innocence; it is, in the modern slang phrase, up to the Crown to prove guilt, and unless you are quite satisfied that the Crown has done this beyond all reasonable doubt, it is your duty to return a verdict of Not Guilty. That does not necessarily mean that the prisoner has established her innocence by proof; it simply means that the Crown has failed to produce in your minds an undoubted conviction of her guilt.

Salcombe Hardy, lifting his drowned violet eyes for a moment from his reporters note-book, scribbled two words on a slip of paper and pushed them over to Waffles Newton. Judge hostile. Waffles nodded. They were old hounds on this blood-trail.

The judge creaked on.

You may perhaps wish to hear from me exactly what is meant by those words reasonable doubt. They mean, just so much doubt as you might have in everyday life about an ordinary matter of business. This is a case of murder, and it might be natural for you to think that, in such a case, the words mean more than this. But that is not so. They do not mean that you must cast about for fantastical solutions of what seems to you plain and simple. They do not mean those nightmare doubts which sometimes torment us at four oclock in the morning when we have not slept very well. They only mean that the proof must be such as you would accept about a plain matter of buying and selling, or some such commonplace transaction. You must not strain your belief in favour of the prisoner any more, of course, than you must accept proof of her guilt without the most careful scrutiny.

Having said just these few words, so that you may not feel too much overwhelmed by the heavy responsibility laid upon you by your duty to the State, I will now begin at the beginning and try to place the story that we have heard, as clearly as possible before you.

The case for the Crown is that the prisoner, Harriet Vane, murdered Philip Boyes by poisoning him with arsenic. I need not detain you by going through the proofs offered by Sir James Lubbock and the other doctors who have given evidence as to the cause of death. The Crown say he died of arsenical poisoning, and the defence do not dispute it. The evidence is, therefore, that the death was due to arsenic, and you must accept that as a fact. The only question that remains for you is whether, in fact, that arsenic was deliberately administered by the prisoner with intent to murder.

The deceased, Philip Boyes, was, as you have heard, a writer. He was thirty-six years old, and he had published five novels and a large number of essays and articles. All these literary works were of what is sometimes called an advanced type. They preached doctrines which may seem to some of us immoral or seditious, such as atheism, and anarchy, and what is known as free love. His private life appears to have been conducted, for some time at least, in accordance with these doctrines.

At any rate, at some time in the year 1927, he became acquainted with Harriet Vane. They met in some of those artistic and literary circles where advanced topics are discussed, and after a time they became very friendly. The prisoner is also a novelist by profession, and it is very important to remember that she is a writer of so-called mystery or detective stories, such as deal with various ingenious methods of committing murder and other crimes.

You have heard the prisoner in the witness-box, and you have heard the various people who came forward to give evidence as to her character. You have been told that she is a young woman of great ability, brought up on strictly religious principles, who, through no fault of her own was left, at the age of twenty-three, to make her own way in the world. Since that timeand she is now twenty-nine years oldshe has worked industriously to keep herself, and it is very much to her credit that she has, by her own exertions, made herself independent in a legitimate way, owing nothing to anybody and accepting help from no one.

Dorothy L Sayers

Dorothy L Sayers