Children of the Levee

LAFCADIO HEARN

Children

of the

Levee

Edited by O.W FROST Introduction by JOHN BALL

COPYRIGHT 1957 BY THE UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY PRESS

COMPOSED AND PRINTED AT THE UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG CARD NUMBER: 57-5834

THE PUBLICATION OF THIS BOOK IS POSSIBLE PARTLY BECAUSE OF A GRANT FROM THE MARGARET VOORHIES HAGGIN TRUST ESTABLISHED IN MEMORY OF HER HUSBAND JAMES BEN ALI HAGGIN

Preface

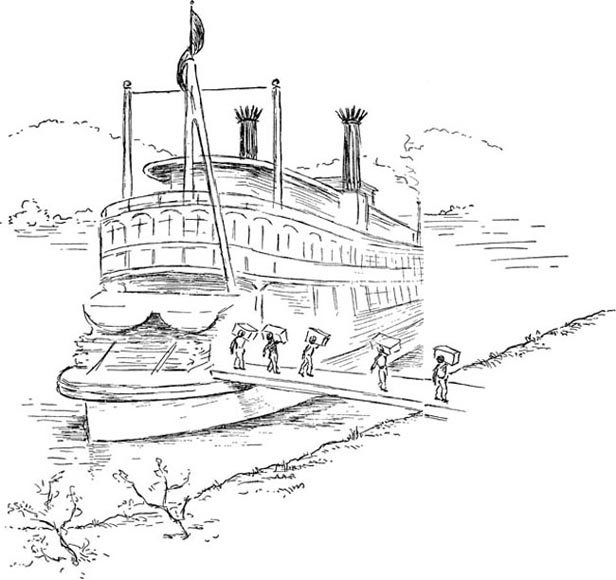

REPRESENTING some of Lafcadio Hearns best work during his early newspaper career, the stories and sketches printed on the following pages portray a weird, brutal, yet colorful societythe levee life of Negro steamboat hands.

A Cincinnati reporter, Hearn wrote these pieces during 1874-1877. To get his material, he accompanied policemen on the beat, peered into levee haunts, witnessed the revels of roustabouts, and listened to their endless superstitions. The simplicity of their animal existence appealed to him, and he frankly admired their strength and beauty, their plaintive song and frenzied dance. Before he left Cincinnati in 1877, he had printed twelve narratives of levee life and lore in the Cincinnati Enquirer and Cincinnati Commercial. These he never reprinted himself. Six were subsequently published by Albert Mordell and Ichiro Nishizaki in posthumous miscellanies. The remaining six are reprinted here for the first time.

Excepting obvious errors of newspaper printers, I present the text of the stories and sketches without editorial alteration. I have, however, omitted subtitles, and in one instance I have altered a title. Hearns titles and subtitles, together with other bibliographical data, are as follows: A Child of the Levee, Cincinnati Commercial, June 27, 1876, p. 4, cols. 4-5; Dolly / An Idyl of the Levee, Cincinnati Commercial, August 27, 1876, 6:2-3, reprinted in An American Miscellany (1924), edited by Albert Mordell; Banjo Jims Story, Cincinnati Commercial, October 1, 1876, 1:5-6, reprinted in An American Miscellany; Pariah People / Outcast Life by Night in the East End / The Underground Dens of Bucktown and the People Who Live in Them, Cincinnati Commercial, August 22, 1875, 3:1-3, reprinted in Occidental Gleanings (1925), edited by Albert Mordell; Jot / The Haunt of the Obi-Man, Cincinnati Commercial, October 22, 1876, 2:2; Ole Man Pickett / Something of His Ranches, and a Bit of His Biography / A Little of Life Among the Lowly, Cincinnati Enquirer, February 21, 1875, 1:3-4, reprinted in Barbarous Barbers and Other Stories (1939), edited by Ichiro Nishizaki; Levee Life / Haunts and Pastimes of the Roustabouts / Their Original Songs and Peculiar Dances, Cincinnati Commercial, March 17, 1876, 2:1-4, reprinted in An American Miscellany; Black Varieties / The Minstrels of the Row / Picturesque Scenes Without SceneryPhysiognomical Studies at Picketts, Cincinnati Commercial, April 9, 1876, 4:6, reprinted in Occidental Gleanings; Butlers / Our Popular Ethiopian Restaurant / Its Bill of Fare and Its Guardian Owl, Cincinnati Enquirer, November 22, 1874, 1:3; Mrs. Lucy Porter, Cincinnati Commercial, July 14, 1876, 8:2-3; The Rising of the Waters, Cincinnati Commercial, January 18, 1877, 8:1; and Genius Loci, Cincinnati Commercial, August 12, 1877, 6:4-5.

O. W. FROST

Contents

Introduction

CINCINNATI in 1869 was a city of manifest destiny. It was the largest inland city in the nation; it had a quarter of a million people and plenty of room to grow. Its expanding trade was fed by rivers, canals, and railroads. Cincinnati was clearly the railroad hub of the West. One editor modestly suggested that the lines east should really be counted as separate railways from the lines north and west, giving the city more railways even than New York.

Cincinnati was building with pride and care. The broad avenues, noble public buildings and monuments, and gracious suburbs would be needed as the city grew in greatness. The Longworths, the Thompsons, and the Tafts had built names and fortunes to be reckoned with. Cincinnati was a cultural oasis in the West and a publishing center for newspapers, magazines, books, and music. National political conventions returned again and again to this pivotal city in politics.

But Cincinnati was not a homogeneous city. Many of the names attached to the growing fortunes were German names. The Germans lived over the Rhinenorth and east of the Miami canal, filling the space between the canal and the hills. The artisans and craftsmen, butchers and brewers lived a life of their own in their German city the size of Meissen or Gttingen today. They brewed their own beer, and made their own beer-garden society and entertainment. They read their own newspapers, printed in German, and attended their German Lutheran churches. The architecture of these churches and of the German homes is still a dominant feature of Cincinnati. Along with the Germans there were nearly 20,000 Irish and a liberal sprinkling of French.

Less numerous than the Germans and Irish, but not less noticeable in the river area of the city were the Negro levee workers. The 1870 census showed 5,904 Negroes in Cincinnati; there were many more just across the river in Kentucky, and there were probably a large number not counted in the census. Near the river were many Negro establishments in the alleys and rows east of the public landing; the heart of Negro Cincinnati, however, was Bucktown, in the area of Sixth and Seventh streets east of Broadway. Bucktown overflowed into the open country to the east; there were shacks, small farms, and a few settlements or clusters of houses. The village of Springfield contained at least 600 Negroes. Two Negro Baptist churches, one African Methodist church, and three other Negro churches were listed in the 1869 Cincinnati guide. The same guide noted the existence of an orphan asylum for Negro children, though no information is at hand concerning this institution. Considering the fact that the equal rights amendment was not ratified until 1870, it is interesting to note that in 1870 nearly one-sixth of Cincinnatis Negroes had attended school. There were in 1874 one Negro high and intermediate school and four Negro district schools employing eighteen teachers and officers.

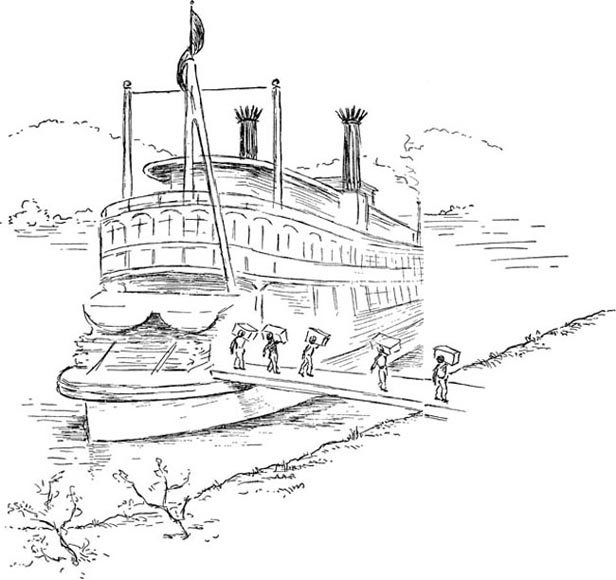

Away from the riverfront area, many Negroes earned a living in domestic service, by farm labor, by tilling their own small plots of ground, by keeping store, by selling produce in the streets, a few by teaching or preaching. However, in the riverfront area most frequented by Hearn the chief Negro occupations were hard labor as stevedores, dockworkers, porters, riverboat firemen or deckhands; boardinghouse or tavern operation; and vice, especially prostitution, gambling, and theft.

Though it was not considered safe for strange white persons in the Negro section of the waterfront, particularly at night, and police protection was sometimes asked by white persons wishing to visit the area, it can be truthfully said that it was no safer for Negroes; anyone who looked prosperous was in danger. Often there were 50 riverboats along the levee at one time, their hundreds of deckhands and firemen on the town to crowd as much living, loving, fighting, drinking, and gambling into their hours ashore as possible. Cincinnati by 1870 had become notorious throughout the Midwest for its wide open waterfront. Violence was common, and arrests were numerous in spite of the fact that police generally did not intrude on the night life of the levee if they could help it. However, beneath the surface the levee was not always as rough as it seemed, as Hearn discovered quickly. There was a kind of cosmopolitan tolerance and acceptance that was the rule. Hearn noted particularly a lack of artificiality and pretense which served to emphasize the essential humanity common to all.