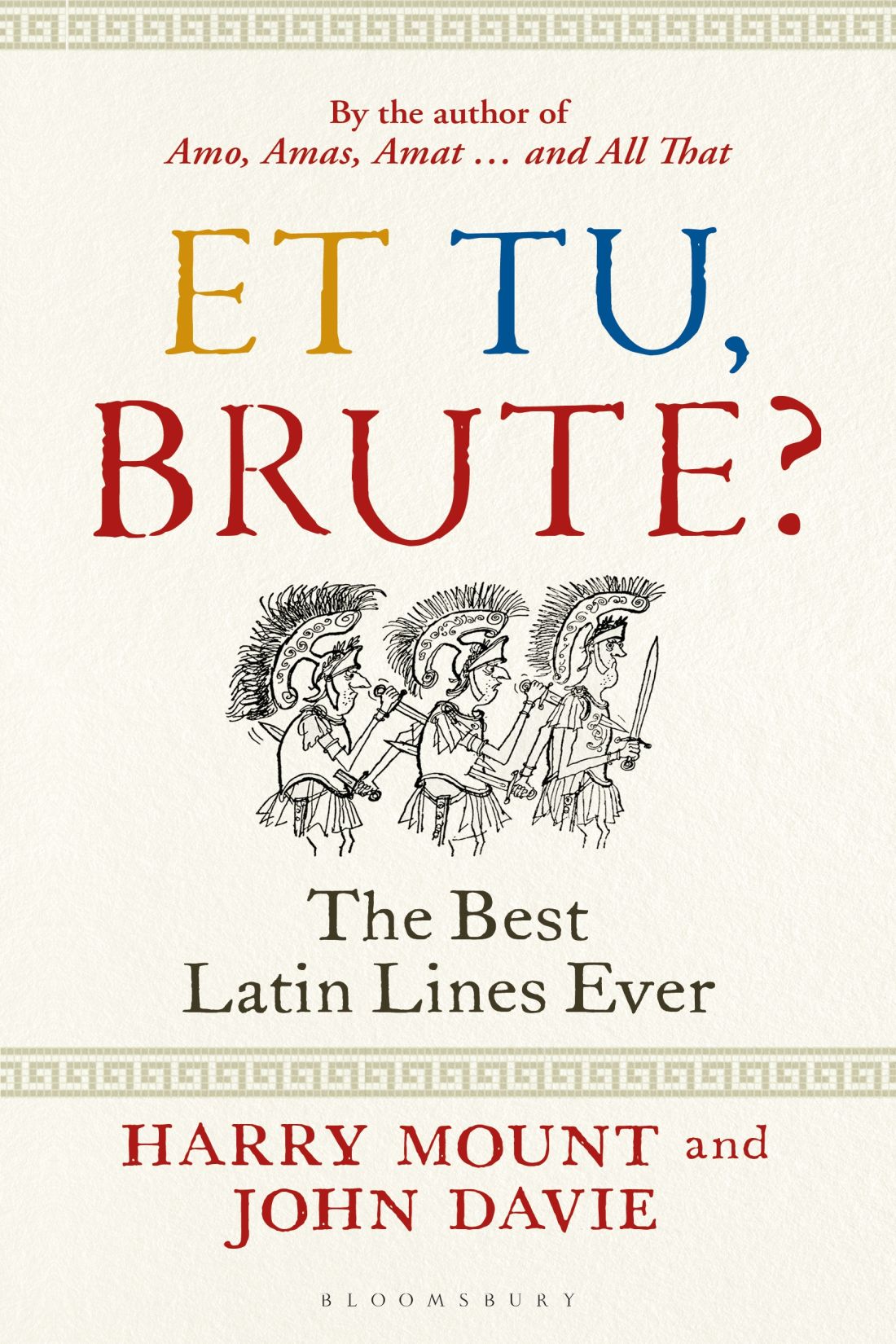

In Memoriam Lindy Dufferin (19412020) and Jasper Griffin (19372019)

Contents

With many thanks to Robin Baird-Smith, Alice Cockerell, Graham Coster, Daisy Dunn, Shomit Dutta, Peter Ireland, Sarah Jones, Michael Keulemans, Gill Markham, Charles Moore, James Pembroke, John Pickford, Katie Walker (particularly for her advice on Father Reggie Foster), Justin Warshaw, A. N. Wilson and Christopher Woodward.

With thanks to Oxford Worlds Classics for permission to print extracts from John Davies translations of Seneca, Horace and Cicero.

With thanks to the Horatian Society, the Patrick Leigh Fermor estate and the Philhellene magazine for his translation of the Horace ode. Many thanks to the Spectator magazine for permission to print an extract from Charles Moores article. Deepest thanks to the Daily Mail , Spectator , Catholic Herald , Literary Review, the Financial Times and the Daily Telegraph for permission to quote from articles by Harry Mount.

Deepest thanks to Philip and Catherine Mould of the Philip Mould Gallery for permission to reprint the portraits of Edward VI and William Arundell.

Many thanks to the following cartoonists for their extremely funny cartoons, which first appeared in the Oldie magazine: Ed McLachlan, Nick Downes, Paul Shadbolt, Nick Hobart and Bill Proud. Were very grateful to Rachel Calder and the estate of Ronald Searle for the sublime cover picture from How to be Topp by Geoffrey Willans and Ronald Searle (Max Parrish, 1954), starring the immortal Molesworth.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If there are any omissions, the authors and publishers would be delighted to hear from copyright owners.

The word of the decade heres hoping it isnt the word of the century is a Latin hybrid.

Coronavirus comes from the Latin corona , meaning crown , and the Latin virus , originally meaning a poisonous secretion from snakes i.e. a kind of venom. Scientists gave the virus the name because those knobbly bits on the surface of the virus are like the crests and balls of a crown. In Latin, corona originally meant a wreath of flowers or, sometimes, of precious metals. You see these delicate golden wreaths of flowers across the ancient world, in Greece and Rome.

The Latin word corona is derived from the Greek word korone . In time, the word corona was used of all crowns, whether floral or not. Our word crown comes from corona . Crowns or coronae were worn in the ancient world by kings and placed on statues of the gods as offerings. In a mocking way, coronae were put on slaves heads, too, when they went up for auction. They were even worn as a cure for headaches.

Virus is also a Latin word, originally derived from the Greek ios . As well as meaning a poisonous secretion by snakes, it was also used in Latin to mean a poisonous emanation from a plant, a poisonous fluid, a nasty manner of speech or disposition, an acrid juice or a magic potion. Used together, though, the words corona and virus these days have only one miserable meaning.

Once again, even with the worst of modern horrors, it is the Latin language that put it first and put it best unless ancient Greek got there first, by lending its alphabet to those horrible virus variants like Delta and Omicron. This book will help you understand the Latin words, like coronavirus, that are still all around us today.

Latin lives on in some corners of Britain even where it shouldnt. Justin Warshaw QC, a family lawyer, still finds Latin useful today in his work:

The law is a goldmine of great Latin tags. Legal Latin was apparently abolished by Lord Woolf in 1999, acting pro bono . Thankfully the judgment was interim and, mutatis mutandis , major reforms have been avoided. The forum is still conveniens , the locus is still in quo , the amicus curiae is still briefed, habeas corpus invoked, a judge can be functus , legitimate reductions remain pro tanto , the Carta remains Magna, the guilty has mens rea for his actus reus and adjournments can still be sine die .

All these legal terms are explained in the glossary of Latin words in English at the back of this book, by the way. It is an updated version of the Latin phrase book in Harry Mounts Amo, Amas, Amat and All That (2006).

And there still is plenty of Latin left in everyday, non-legal life, even if some people want to get rid of it. As Charles Moore wrote in the Spectator on 29 May 2021:

O tempora, o mores. A worried report from the Social Mobility Commission claimed last week that many top civil servants know Latin, and use it, thereby excluding their less privileged colleagues.

I am trying to help stamp this practice out by constructing a lingua franca purged of hard-to-understand terms from the snobby old Romans e.g. (exempli gratia) circus, video, doctor, bonus, exit, femur, stet, quantum, trans, memorandum, focus, alumnus, camera, conductor, radius, maximum, minimum, major, minor, senior, junior, media, gratis, post-mortem, ego, versus, data, species, penis and vagina, i.e. (id est) quite a lot of words.

It is hard work, but we must jettison stuffy old concepts like habeas corpus, pro bono, sub judice, de jure, de facto and de minimis non curat lex all so twentieth-century.

Then there are all those initials. AD is now on the way out, but why must we make people uncomfortable by using a.m./p.m. (ante and post meridiem) to tell the time, and how dare the Queen call her herself DG Reg FD on our coinage?

It must, a fortiori, be intimidating for would-be civil servants from deprived backgrounds to have to wrestle with a CV (curriculum vitae), and ipso facto, become persona non grata. Res ipsa loquitur, QED (quod erat demonstrandum), etc. (et cetera). Latin: RIP (requiescat in pace). When levelling up, it is much better to use good old English words like hoi polloi.

Again, youll find the Latin words Charles Moore mentions in this books glossary. A lot of them have become English words used by everyone like senior and junior. Charles Moore might also have included the Latin word spectator . It means exactly the same in Latin as in English and it also happens to be the name of the magazine he wrote these words in.

We rarely stop to think what extraordinary survivals they are: completely intact words transported all the way from ancient Rome, unsullied by a journey across a continent and several millennia.

Other Latin phrases, though, once in more regular use like a fortiori are in decline. This book aims to reverse that decline. How sad it would be if those pure Latin words disappeared from the English language even if well always have Latin- and Greek-inspired words.

As well as defining Latin words used in English, this book principally shows how the Romans really looked at the world in their native language: how they looked at love, sex, politics and everyday life. Latin isnt an austere relic to be worshipped behind glass, at a distance, in a museum. Latin is there to make you laugh, move you to tears, and charm you by its beauty and cleverness. But by its pleasing cleverness, not its scary cleverness.

That pleasing cleverness is why people still drop Latin into their speeches to add a little extra heft. The Queen did it in her speech at the Guildhall on 24 November 1992. Windsor Castle had just burned down. Princess Anne had divorced. The marriage of Charles and Diana was crumbling and Prince Andrew had separated from Fergie who had just had her toe sucked by the American financier John Bryan. Thats why the Queen declared: In the words of one of my more sympathetic correspondents, it has turned out to be an annus horribilis.