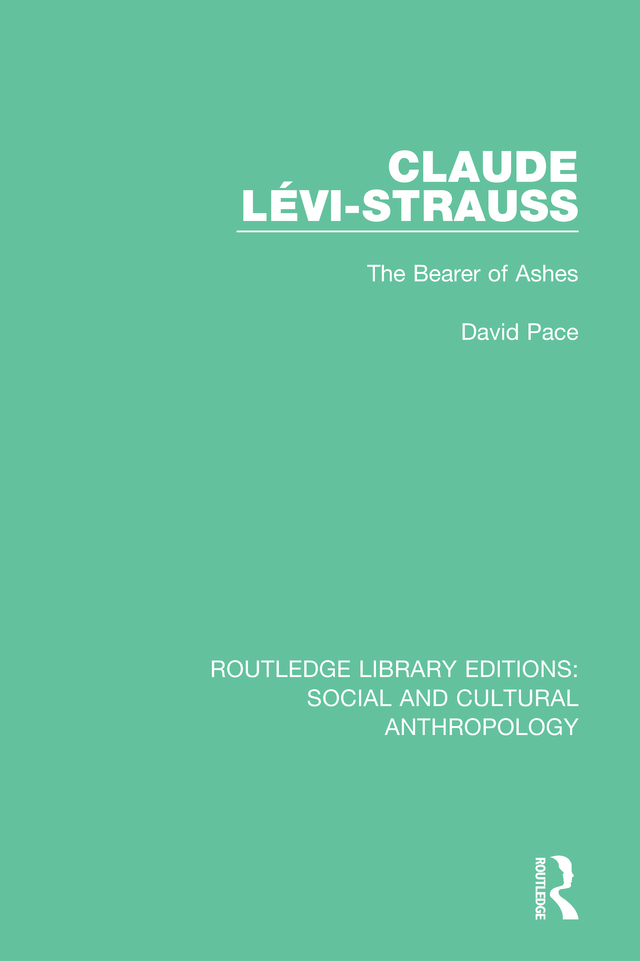

ROUTLEDGE LIBRARY EDITIONS: SOCIAL AND CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY

Volume 2

CLAUDE LVI-STRAUSS

Claude Lvi-Strauss

The Bearer of Ashes

David Pace

First published in 1983 by Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd

This edition first published in 2016

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1983 David Pace

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-138-92596-0 (Set)

ISBN: 978-1-315-68041-5 (Set) (ebk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-92855-8 (Volume 2) (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-68162-7 (Volume 2) (ebk)

Publisher's Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

Claude Lvi-Strauss

The Bearer of Ashes

David Pace

First published in 1983,

by Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd

9 Park Street, Boston, Mass. 02108, USA, 39 Store Street, London WC1E 7DD, 296 Beaconsfield Parade, Middle Park, Melbourne, 3206, Australia, and Broadway House, Newtown Road, Henley-on-Thames, Oxon RG9 1EN Set in IBM journal 10 on 12 pt by

Academic Typing Service, Gerrards Cross, Bucks and printed in the United States of America

Copyright David Pace 1983

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except for the quotation of brief passages in criticism.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Pace, David.

Claude Lvi-Strauss, the bearer of ashes.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. Lvi-Strauss, Claude. 2. Structural anthropology. 3. Ethnology-Philosophy.

I. Title.

GN21.L4P23 1982 306 82-16166

ISBN 0-7100-9297-0

To Jim Harrison

without whom this book would never have been started

and Ivan Karp

without whom it might never have been completed

Contents

In the dozen years in which I have been involved in this project I have been the recipient of many, many kindnesses without which this work would probably never have appeared. It is impossible for me to acknowledge them all, but I would like to make an attempt to thank a few of the persons who were particularly important in this process.

I wish to thank Jim Harrison, who filled so admirably and for so many years the roles of teacher and friend, and who said one Sunday morning on the front porch: 'Yeah, but the person to really read is this French anthropologist, Lvi-Strauss ...'

Professor Franklin Baumer, who had the patience and understanding to allow a rather headstrong young graduate student to find his own way.

Ellen Dwyer, who supported me through several crises which almost saw the premature end of this work.

Jim Dublin, who helped me grow into it and beyond it.

Ivan Karp, whose practical assistance, encouragement, and intellectual stimulation were absolutely necessary for the completion of the manuscript.

Jim Riley, whose confidence in my work helped me through a particularly difficult time.

Gene Dye, who was so willing to help a virtual stranger in a time of need.

Dave Delauter, who gave his time so generously in the final preparation of the manuscript.

And Charlotte Hess, whose patience and assistance were demanded so much in the last hectic months of this project.

I also wish to thank Professor Lvi-Strauss himself for his personal kindness to and interest in a rather intimidated graduate student who called upon him at the College de France in May 1970.

In the spring of 1981 the journal Lire examined the intellectual climate in France a year after the death of Jean-Paul Sartre by asking some 600 intellectuals, students, and politicians the question: 'Who are the three living, French-speaking intellectuals whose writings appear to you to have exercised the deepest influence on the evolution of ideas, letters, science, etc?' To no one's great surprise the most common choice of the 448 respondents to the poll was Claude Lvi-Strauss. His 101 votes put him ahead of Raymond Aron (84) and Michel Foucault (83), who were virtually tied for second place. The other popular choices were Jacques Lacan (51), Simone de Beauvoir (46), Marguerite Yourcenar (32), Fernand Braudel (27), Michel Tournier (46), Bernard-Henri Levy (22), and Henri Michaux (22).

This somewhat unscientific sample simply reaffirms what is common knowledge about the 'pecking order' of French intellectuals. Since the early 1960s Lvi-Strauss has had a secure position within the Gallic pantheon. He was long described as the most serious of Sartre's rivals, and now that the latter is dead, Lvi-Strauss stands at the top of the heap.

Lvi-Strauss's position in this poll does, however, raise an interesting question for the intellectual historian - a question which becomes immediately obvious when he is compared with Sartre, who would most certainly have been at the top of the list had he still been alive. The great popularity of Sartre is easy to understand. His ideas were often demanding, but they were always directly relevant to the issues which most concerned his contemporaries. Both as an existentialist and as a leftist, he remained in contact with the concerns of his time. Moreover, for those unable to follow the philosophical subtleties of Being and Nothingness or the Critique de la raison dialectique, Sartre provided essays, plays, and novels through which his ideas could be more easily assimilated. Finally, Sartre's life itself provided that element of theater which the French have long demanded in their intellectual idols. From his days as a student until the moment of his death, Sartre's life was a heroic quest for meaning, and its drama captured the attention of the French public for forty years.

By contrast, the life of Lvi-Strauss seems pale and, for long periods, rather uninteresting. To be sure, there was an intrinsic drama to the years between 1935 and 1942 when he explored the Brazilian interior, fought in the Second World War, and then fled to the United States to escape the Nazis. But since the mid-1940s Lvi-Strauss's life has lacked the excitement which characterized that of Sartre.

In the early 1950s, for example, while Sartre was embroiled in struggles with Albert Camus, Raymond Aron, and Maurice Merleau-Ponty about terrorism and the left, Lvi-Strauss was delivering lectures on 'primitive' religion as the Directeur d'Etudes at the cole Pratique des Hautes tudes. In 1959, when Sartre was risking his life in the resistance to the war in Algeria, Lvi-Strauss was absorbed in his new duties as the first anthropologist to teach at the Collge de France. The Revolt of 1968 found Sartre in the streets and Lvi-Strauss in his Laboratory of Social Anthropology; and in the mid-1970s Sartre's epic struggle to get into jail to protest against the trial of leftist journalists roughly coincided with Lvi-Strauss's entry into the conservative Acadmie franaise.