Contents

In memory of Gregory D. Cantrell

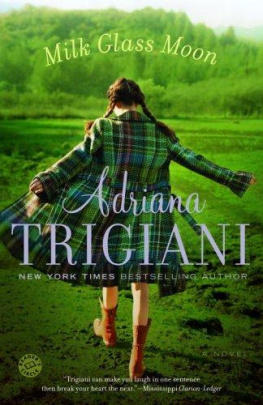

Crackers Neck Holler

1998

A s the wind blows through our bedroom window, it sounds like a whistling teakettle. As I wake, for a split second, I forget where I am. As soon as I see our suitcases piled next to the closet door, in the exact place where we dropped them, I remember. Ettas wedding, though it was just one week ago, already seems like a faraway dream.

When we drove up the road last night, our home in Crackers Neck Holler looked like a castle in the mist. The first days of autumn always bring the cold fog, which makes every twist and turn on these mountain roads treacherous. Etta used to call the September fog the Murky Murk. She told me, I dont like it when I cant see the mountains, Mama.

This morning theyre in plain view again. Since weve been gone, the mossy field out back has turned to brown velvet, and the woods beyond have a silver patina from the first frost. I take a deep breath.

In a way, its good to be home, where everything is in its place. The same beam of sunlight that comes over the mountain at dawn splits our house in two, one half drenched in brightness and the other in dark shadow. Shoo the Cat sleeps on the same embroidered pillow on the old rocker, as he has every night since he came to stay. Small, familiar comforts matter when everything is changing.

I pull on my robe. Before I leave the room, I tuck the quilt around my husband. Hes not waking up anytime soon; his breath is rhythmic and deep. I make my way through the stone house, and it feels so emptyas it did before there were children. I dont know if there is a sound lonelier than the silence of everybody gone.

The first thing I do is measure the coffee into the old two-part pot Papa gave me from a shop in Schilpario. I put the pot on the stove, and blue gas flames shoot up when I turn the dial. Its chilly, so I take a long, thin match from the box on the mantel and light the fire in the hearth. One of the things I love best about my husband is that he never leaves a fireplace barren. No matter what time of year, theres a crisscross of dry logs on a bed of kindling and a neat newspaper bundle good to go. The paper crackles, and soon the logs catch and the flames leap up like laughter from a school yard.

Theres a note on the fridge from my friend Iva Lou: Welcome home. How was it? Call me. When I look inside, shes stocked us for breakfast: a few of Hope Meades rolls (I can tell by the shape of the tinfoil package), a jar of fresh jam, a crock of country butter, and a glass carafe of fresh cream, no doubt from her aunts farm down in Rose Hill. What would I do without Iva Lou? I really dont like to think about it, but I do; in fact, Ive been obsessed with loss lately. The past year brought my happy circus to an abrupt closeSpec died, Pearl moved to Boston, and I lost Etta to her new life in Italy. I dont like change. I said that so much, Jack Mac finally said, Get used to it. Doesnt make it one bit easier, though, not one bit.

Theres a deep stack of mail waiting for me on the table. Bills. Flyers. A letter from Saint Marys College requesting alumnae donations. An envelope for Jack from the United Mine Workers of Americaanother cut in benefits, no doubt. A puffy envelope from the home shopping channel containing a pair of earrings I bought for Fleetas birthday on back-order (took long enough). Underneath is a postcard from Schilpario, Italy, the town wed just left a day ago. I flip it over quickly and read:

Dear Ave Maria, By the time you get this, Etta will be married, youll be home, and Ill be back in New York. This is a reminder. Start living your life for YOU. Got it? Love, Theodore.

I put the postcard from my best pal under a magnet on the door of the fridge. Ill take any free advice I can get. Noticing the clutter on the doorall reminders of my daughter and her senior year of high schoolI begin to take things down. Ettas high school graduation schedule from last June is taped to a ribbon of photos she took in a booth at the Fort Henry Mall. She looks like a girl in the pictures. Her coppery hair in long braids makes her seem even younger. She is young, too young to be married, and too young to be so far from home. I close my eyes. Is it ever really possible for a mother to let go?

The coffee churns up into the cap of the pot, signaling its ready to be poured. I grab an oven mitt off its hook and pour the coffee into the mug. The delicious scent of a hickory fire and fresh-roasted coffee is the perfect welcome home.

I kick the screen door open and go out on the porch to watch the sun take its place in the sky over Big Stone Gap. Autumn is my favorite time of year; it seems to say Let go with every leaf that turns and falls to the ground and every dingy cloud that rolls by overhead. Let go. (So hard to do when your nature tells you to hang on.)

At the edge of the woods, a spindly dead branch high in a treetop crackles under the weight of a blackbird, which flies off into the charcoal sky until its a speck in the distance. I have to remind Jack that the property line needs some attention. Hes always so busy fixing other peoples houses that our needs are last on the list. The wild raspberry bushes have taken over the far side of the field, a tangled mess of wires and vines. Pruning, composting, rakingall those chores will occupy us until the winter comes.

I hear more snapping coming from the woods, so I squint at the treetops, expecting more blackbirds, but there is no movement. The sound seems to be coming from the ground. I lean forward as I sit and study the woods. I hear more crackling. What is it? I wonder. Then something strange happens: I have a moment of fear. I know theres nothing to be afraid ofthe sun is up, Jack is inside, and theres a working phone in the kitchenbut for some reason, I shudder.

As I stand to go back into the house, I see a figure in the woods. It looks like a man. A young man. With curly brown hair. I can see that much from my place on the porch, but not much elsehis face is obscured behind the thick branches. I raise my hand to wave to him, and open my mouth to shout to him, but as soon as I do, he is gone. I close my eyes and listen for more footsteps. There is nothing but silence.

What are you doing out here? Jack says from the door. Its cold. Come inside.

I follow him into the house. Once were in the kitchen, I throw my arms around him. Honey, I saw something. Someone.

Where?

In the woods.

When?

Right now. This second. He was walking along the property line. I saw him.

Well, its hunting season.

He wasnt a hunter.

Maybe hes hiking.

No.

What, then?

It was Joe.

Joe? Jack Mac is confusedso confused, he sits. Our Joe?

I nod.

Jesus, Ave Maria. You know thats impossible.

I know. My eyes fill with tears. But I think Id know my son when I see him.

Without hesitating, Jack takes his work jacket off the hook, pulls it on, and goes outside. I watch him as he walks across the field and into the woods. He surveys our property line, looking for the young man. Sometimes he takes a few steps into the woods and disappears. I dont know why, but Im relieved each time he reemerges. I stand at the window waiting as he checks the side yard and his wood shop. I half expect him to return with someone. With Joe. I hear the bang of the screen door.

Theres no one there. It was a long trip. Youre tired. Youre imagining things. Really. Jack takes off his jacket. I didnt see any footprints in the mud. Nothing.

Im not making it up.

Jack sits and pulls me onto his lap. What did he look like?

Next page