Acknowledgements

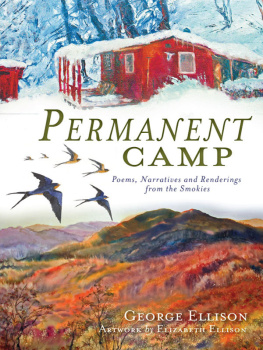

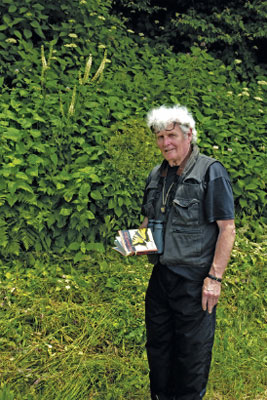

Just listing the names of those who have supported us through the years would fill a telephone directory. But you know who you are and how much we appreciate your being there for us when it counted. The three current editors of the publications in which these essays first appeared, in one guise or another, and the editors at The History Press who are transposing a generous helping of them into this collection, need to be mentioned: Bruce Steele at the Asheville Citizen-Times; Scott McLeod at Smoky Mountain News; Dr. A. Joseph Pollard with Chinquapin: The Newsletter of the Southern Appalachian Botanical Society as well as Banks Smither, Adam Ferrell and Ryan Finn at the press. Dr. Pollard and Dr. Timothy P. Spira provided valuable commentary on the essays. Our thanks go to Lydia Macauley for the Table Mountain Pine artwork (on the front cover), as well as The Cedar Glades artwork, both by Elizabeth Ellison; to Tim Spira for the Belted Kingfisher artwork by Elizabeth Ellison (on the back cover), as well as the photograph of the author; and to musician Angela Martin for the cedar glades group photo and lyrics.

Rave on Shining Water was published in Flycatcher, no. 2 (January 2013). The Yucca and Its Moth was published in the American Gardner: The Magazine of the American Horticultural Society 94 (MayJune 2015).

About the Author and Artist

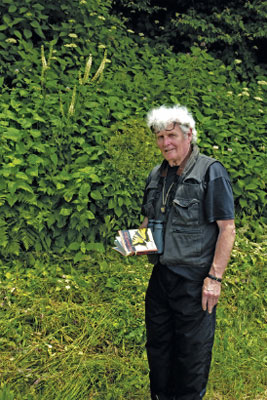

GEORGE ELLISON is a writer and naturalist. He teaches workshops in bird, wildflower and fern identification for the North Carolina Arboretum and other facilities and writes natural history columns for the Asheville Citizen-Times, Smoky Mountain News and Chinquapin: The Newsletter of the Southern Appalachian Botanical Society. The seven books of his that have been published by The History Press are listed at the front of this volume. He is currently coauthoring a biography of Horace Kephart to be published by the Great Smoky Mountains Association. In 2012, he was the recipient of the Wild South Roosevelt-Ashe Award for conservation journalism. And in 2016, he was named by the Great Smoky Mountains Association as One of the 100 most influential figures in the history of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

www.georgeellison.com

ELIZABETH ELLISON is a professional artist who resides in Western North Carolina with her husband, George Ellison. She has been owner/operator of Elizabeth Ellison Gallery in Bryson City since 1986, and her work is widely collected in the United States and other countries. She works in acrylic, oil, watercolor, clay and mixed media and often incorporates her handmade plant fiber paper into her paintings. Her work is singular and strongly expresses her immersion in the natural world. It can be described as a celebration of the Spirit of Place.

www.elizabethellisongallery.com

1

Geography of Place

INNER AND OUTER LANDSCAPES

This essay was written at the request of Brent Martin, regional director for the Southern Appalachian office of the Wilderness Society, for a symposium of writers from Western North Carolina held at the Handmade in America facility in Asheville, North Carolina, on November 7, 2014, to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the Wilderness Act. That 1964 legislation established the National Wilderness Preservation System and created the process by which Wilderness Areas are designated and some of our nations most beautiful and vital wild places are protected. Other writers taking part included Charles Fraser, Katherine Stripling Byer, Thomas Rain Crowe, Wayne Caldwell, John Lane and Catherine Reid. I was unable to attend, but Brent suggested that if I wrote something appropriate, he would read it in my absence. It was subsequently published in the summer 2015 issue of Chinquapin: The Newsletter of the Southern Appalachian Botanical Society.

Lets open with a quote from Barry Lopezs essay A Literature of Place, first published in the Portland Magazine in 1997:

Over time I have come to think of these three qualitiespaying intimate attention; a storied relationship to a place rather than a solely sensory awareness of it; and living in some sort of ethical unity with a placeas a fundamental human defense against loneliness. If youre intimate with a place, a place with whose history youre familiar, and you establish an ethical conversation with it, the implication that follows is this: the place knows youre there. It feels you. You will not be forgotten, cut off, abandoned.

Right away, Lopez has unapologetically anthropomorphized the landscape. It is immediately placed on equal, if not superior, footing with human observers. There was a time not so long ago when the powers that be in the Behaviorist School would have had him executed for that sort of thinking.

Lopezs language is Whitmanesque: The place knows youre there it feels you, he exclaimed. It is you who might be forgotten, cut off, abandoned. Landscape is not a commodity for either Whitman or Lopezit was and is living entity. Lopez stressed the importance of geography as a gateway to this sort of intimacy. He is a traveler to faraway places. I am a traveler within nearby horizons. While I have been exploring my front yard for going on forty years now, he has been venturing into the Antarctic or the Tanami Desert in Australia and similar places. But our methods and objectives are not totally dissimilar.

Lopez believes, as do I, that two landscapes engage each other in our imaginations, one outside the self, the other within. I am a would-be dweller in both of those landscapes. And I am absolutely confident that a firm sense of where you are enhances your understanding of who you are.

The natural history essays I write for various publications depict the origins, landscapes, plants and animals of the Southern Blue Ridge Province from Mount Rogers in southwest Virginia to Mount Oglethorpe in north Georgia. But the focus is almost always narrowed to Western North Carolina, especially the southwestern tip from Asheville to Murphy, the North Carolina and Tennessee sides of the Great Smokies and my aforementioned front yard, which is, in case youre wondering, situated at the center of the universe.

It gives me pleasure to recall that the creek that flows through the center of the universe heads up in the Smokies below Clingmans Dome flows into what is placid Lake Fontana in summer and the howling wilderness of the lower Tuckaseigee in winter on its way to the Gulf of Mexico via the Little Tennessee, Tennessee, Ohio and Mississippi.

At night, I dont count sheep. I name the mountain ranges and rivers from east to west. And then I dream of special places Elizabeth and I have discovered and return to with regularity. Along the Blue Ridge Parkway at the Wolf Mountain Overlook, there are vertical seepage walls where emerald-green sphagnum mats have accumulated in which thousands of carnivorous round-leaved sundews reappear each year. At the same spot, there are plants such as Blue Ridge St. Johns-Wort and Showy St. Johns-Wort, pink-shell azalea, skunk goldenrod and others classified as Blue Ridge endemicsthat is, they are found here or in this general area and no place else in the world. Add other plants like Michauxs saxifrage, little green orchis, grass-of-Parnassus, false asphodel, hay-scented and lady ferns and American bugbane and you have a setting that is not far from being edenic. Im not sure the hanging gardens at Wolf Mountain or other settings like Alarka Laurel (situated where Jackson, Macon and Swain Counties corner in the Cowee range) or High Rocks (situated on the crest of Welch Ridge overlooking the North Carolina flank of the Smokies) are sacred places, but I do know they have become touchstones of spiritual consequence in our lives.

Next page