ANGLO-ENGLISH ATTITUDES

Anglo-English Attitudes brings together Geoff Dyers best journalism and other writing from 19841999. There are studied meditations on photographers (Robert Capa, William Gedney, Henri Cartier-Bresson), painters (Bonnard, Gauguin) and musicians (John Coltrane, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Def Leppard), close critical engagements with writers (Albert Camus, Michael Ondaatje, Martin Amis) and idiosyncratic reflections on boxing, comics, Airfix models and Action Man.

Geoff Dyer is the author of Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi and three previous novels, as well as nine non-fiction books. Dyer has won the Somerset Maugham Prize, the Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse Prize for Comic Fiction, a Lannan Literary Award, the International Center of Photographys 2006 Infinity Award for writing on photography and the American Academy of Arts and Letters E.M. Forster Award. In 2009 he was named GQs Writer of the Year. He won a National Book Critics Circle Award in 2012 and was a finalist in 1998. He lives in London.

www.geoffdyer.com

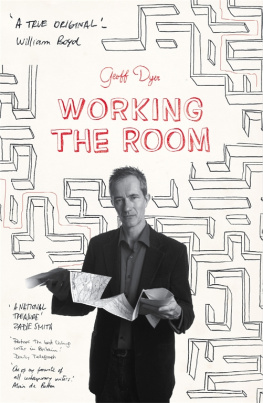

Also by the author

Zona

Working the Room

Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi

The Ongoing Moment

Paris Trance

Out of Sheer Rage

The Missing of the Somme

The Search

But Beautiful

The Colour of Memory

Yoga For People Who Cant Be Bothered to Do It

Ways of Telling: The Work of John Berger

This paperback edition published in Great Britain in 2013 by Canongate Books Ltd, 14 High Street, Edinburgh, EH1 1TE

www.canongate.tv

This digital edition first published by Canongate in 2013

Collection copyright Geoff Dyer 1999

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All characters in this publication other than those clearly in the public domain are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved.

First published in Great Britain in 1999 by Abacus,

an imprint of Little, Brown Book Group,

100 Victoria Embankment, London EC4Y 0DY

Lines from Egon Schiele by Jeremy Reed (from Nineties, Cape 1990) and Las Casas by Michael Hofmann (from Corona, Corona, Faber 1993) are reproduced by kind permission of the authors. Lines from September 1, 1939 by W. H. Auden (from The English Auden) are reproduced by kind permission of Faber and Faber Ltd.

Original publication details for each piece appear in the acknowledgements on pp 363364

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library

ISBN 978 0 85786 403 1

eISBN 978 0 85786 334 8

Typeset in Berkeley by M Rules

This book is for Chris Mitchell and for Charles De Ledesma

List of Illustrations

One might reasonably ask: why tigers instead of leopards or jaguars? I can only answer that spots are not pleasing to me, while stripes are. If I were to write leopard instead of tiger the reader would immediately sense that I was lying.

Borges

Introduction

When writers have achieved a high enough profile they are sometimes prevailed upon to publish their occasional pieces (i.e. their journalism). The author agrees, reluctantly, modestly Martin Amis offered his first collection, The Moronic Inferno, with all generic humility because this kind of put-together is considered a pretty low form of book, barely a book at all.

My own case and my own opinion of such collections is a little different. For a start it was my publisher who was prevailed upon and I was the one doing the prevailing. Almost as soon as I began writing for magazines and newspapers I hoped one day to see my articles published in book form. If a piece was mauled by editors or subs I consoled myself with the thought that one day I would see it re-published exactly as intended, in a book. (With this option in mind I often sent off one version for immediate publication, and kept another, longer one for future use.) If were being utterly frank, there were times when it was only the prospect of one day being able to publish my journalism that kept me writing proper books: do a few more novels, I reasoned, and maybe my obscurity will be sufficiently lessened to permit publication of the book I really care about, a collection of my bits and pieces.

I especially wanted to publish such a book because I virtually never read the review pages of newspapers or magazines. If I see a piece by a writer I admire in a paper I very rarely read it; but as I look through catalogues of forthcoming books the ones that catch my eye are collections of exactly these pieces that I have neglected to read in their original context. Since I prefer to read other peoples journalism in book form, its not just vanity that makes me want to see my own presented that way too. When I broached the possibility at first, hesitantly, hypothetically, around the third glass of wine, then, increasingly shamelessly, before wed even ordered our starters my editor asked if these pieces would be linked, if there might be some way of passing off these bits and bobs as a coherent book organised around a defining theme. Would it be possible, for example, to compile a book of my writings about photography? Or American writers?

Possible, yes, but, from my point of view, not at all desirable because it was, precisely, the unruly range of my concerns that I was keen to see represented in a single volume. I wanted the book to serve as proof of just how thoroughly my career (though I should add immediately that writing, for me, has always been a way of not having a career) had avoided any focus, specialism or continuity except that dictated by my desire to write about whatever I happened to be interested in at any given moment.

It seemed to me or so I claimed at the four- or five-glass mark that this variegation might even give the collection a kind of unity or coherence. The more varied the pieces, I argued, the more obviously they needed to be seen together as the work of one person because the only thing they had in common was that they were by that person. If there was one thing I was proud of in my literary non-career it was the way that I had written so many different kinds of books; to assemble a collection of articles would be further proof of just how wayward my interests were. Such a collection would also show that I had remained faithful to the example of my mentor, John Berger. In Ways of Telling, my dull little book about him, I claimed that Bergers ability to write on so many different subjects in so many different ways was an indication not only of his ability but also his success as a writer; over the years this was exactly the kind of success, of freedom, I tried to carve out for myself. Introducing his collection of articles on French writers and thinkers, The Word from Paris, John Sturrock counsels that literary journalists do well professionally to have a territory that is known to be theirs, and not to lay claim to a diffuse expertise qualifying them to write about anyone or anything. If Sturrocks right and he almost certainly is then I feel very fortunate to have remained conspicuously in the wrong for so long.

A distinction is often made between writers own work which they do for themselves and the stuff they do for money. The ideal, in this scenario, is to be able to devote all your time to your own writing. Again, my case is rather different. Most of the journalism I do is as much my own writing as, well, my own writing. Whereas Martin Amis talks about writing his

Next page