A LINE IN THE RIVER

Contents

This is, without doubt, the most personal and ambitious book I have ever attempted to write. I say this not so much out of a sense of pride, but, rather, astonishment. Had I known, at the outset, what I was letting myself in for, in all likelihood the project would have been delayed, if not abandoned in despair.

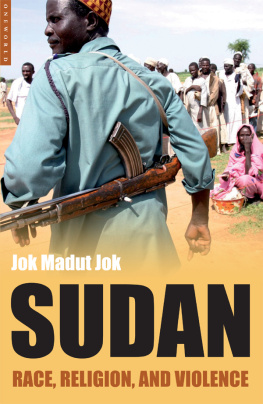

Of course, life doesnt actually happen like that. This book emerged partly from a sense of anger and outrage at what was happening in Darfur. I couldnt quite believe that nothing had been learned from past mistakes. Khartoum seemed determined to continue along the same doomed path it had pursued throughout its recent history; denying the countrys cultural and ethnic diversity in a stubborn display of delusion and arrogance.

The world at large, also, seemed not to have made much progress in the intervening years, and people with no prior knowledge were leaping into the fray, emotively declaring it a genocide. Darfur felt like a moment of dj vu that took me back to the time I was writing my first novel. Then it had been famine that brought the worlds gaze to rest briefly on Ethiopia and Sudan. It felt as if, for over twenty years, I had been trying to address the absence of context against which these tragedies took place, and had achieved nothing. Darfur felt, in a very personal way, like a declaration of failure on my part.

Now I begin to see this book as the culmination of everything I have ever written. It is also, somehow, organically related to all those other books that have absorbed me over the years, which I had to write in order to reach this point. I began my first novel thinking I was going to write about a young man seeking to discover the part of his background that he doesnt know. He thinks this will complete him, resolve all his doubts, make him whole. That novel led me inwards and backwards in time over successive novels that sought to understand the nature of this vast and little-known country, and to come to terms with my own relationship to it. It was impossible to write about one thing without illustrating the context, filling in the blanks, sketching the landscape, and I seem to have been doing that ever since.

In a similar way, this project soon began to spiral out of hand. It felt like a book that was open-ended, limitless. It felt as if I could just go on writing and writing. I was trying to find an end point, and at the same time did not want to. I encountered another problem. Being primarily a writer of fiction, I came to this with the notion that to write reportage was to deal in cold, clear facts, but as soon as I put pen to paper, as it were, I found the account bending itself to fit my narrative, much as a work of fiction might. Writing is writing, and once the imagination engages with reality it finds its own course. So what is this book? Fiction, non-fiction? Personal memoir, political history, travelogue? I still find it hard to define. In an age when transgressing boundaries is in vogue, it seems to be neither one thing nor the other, although fashionable was the last thing I was trying to be. The form of the book reflects the time in which it was written, the age of uncertainty in which we live.

Over the years I had lost contact with friends and family in Khartoum. Going back was not only emotional, it also triggered an existential crisis of sorts. Who was I without this place that I had written about for so long? What would I become? How would I go on? What would I write about when this was over? It became apparent to me that I couldnt really go back, not permanently. Although I enjoyed visiting, too much had changed. I had changed. I had too many commitments elsewhere. This realisation lent the work a sense of finality, as if this would indeed be the last book I would ever write about Sudan. Perhaps, subconsciously, this too was a reason for not finishing.

The conflict between trying to find a point of closure, and wanting it to go on indefinitely, stemmed also from the conviction that I could never write a book that would fully do justice to the matter in hand. At times it felt as though I was grappling with a subject so profound and so abstract as to evade all my attempts to capture it. In rare moments it felt as though I had reached a point of sublime beauty in which everything came together to transcend time and place.

The time frame I adopted coincided with the six years of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) that had brought the civil war to an end, and closed, roughly, with secession. It ends before the South twisted its newly gained independence into its own internecine strife, a conflict that feels like an extension of the never-ending war that had gone before.

The notion of independence now seems hopelessly outdated. The intervening decades have largely witnessed a pattern of rising economic strength in the West matched by spiralling decay elsewhere. A pattern of dystopian proportions dominates the narrative of what used to be called the Third World. Almost daily we are faced with images of the desperate measures people are willing to take, risking their lives and those of their loved ones, in the hope of reaching the West. In their own homelands they see no future, only a lifetime of destitution and hopelessness. It is a damning indictment of any idea of progress.

This is not an academic thesis, it is a book of impressions. I was constantly struck, as I was writing, of the parallels between Sudan and the problems in the world today. Racial tension in the United States, the rise of the far right in Europe, the persecution of minorities all over. The West faces an existential crisis as social change challenges its understanding of its cultural and historical heritage. The key to social harmony and progress, in Sudan and elsewhere, lies in how we deal with diversity. This is not a problem that is about to go away, as the planet grows smaller and resources dwindle. Climate change aside, the greatest challenge facing the human race will be how to live together. In this sense, Sudans case offers a microstudy of the perils of not meeting that challenge with honesty and integrity.

I am acutely aware that a book like this will be seen by some as an endorsement of the view that Africa is a hopeless case. The head-in-the-sand school of cultural advancement. The well-meaning Marxists as well as the apologists for imperialism. I would insist that all is not doom and gloom. There has to be a place for constructive criticism. I dont believe in pretending that all is wonderful, but by the same token I do not believe we can give up. We must have hope. And much of what I have seen of Africa is encouraging, but the continent has suffered, since the era of independence in the 1960s, from trying to catch up with the West, rather than finding its own path. The West, eager to secure its own interests, has encouraged this idea. Africa needs imaginative solutions to its own unique problems. Some of that, I believe, is reflected here.

Now, even though the book is (more or less) concluded, I will still, in conversation, recall an incident or an anecdote and be seized by the conviction that it should have been included. There are countless people whose names do not appear here, but who were a source of inspiration to me growing up and whose spirit I have to some extent tried to capture. If this book is dedicated to anyone then it is to those people, my parents included, who inspired me in their selfless commitment to achieving the nation, to making the world a better place, not for the few, but for the many. Journalists, writers, academics, painters. People who were willing to suffer the consequences and who paid a price for their struggle. Today, such idealism has given way to the negative tropes of polarisation, religious sectarianism, cynicism and violence. All of which reject the idea of conversation in favour of closure, at a time when compromise and compassion are needed more than ever.