All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

DOUBLEDAY and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

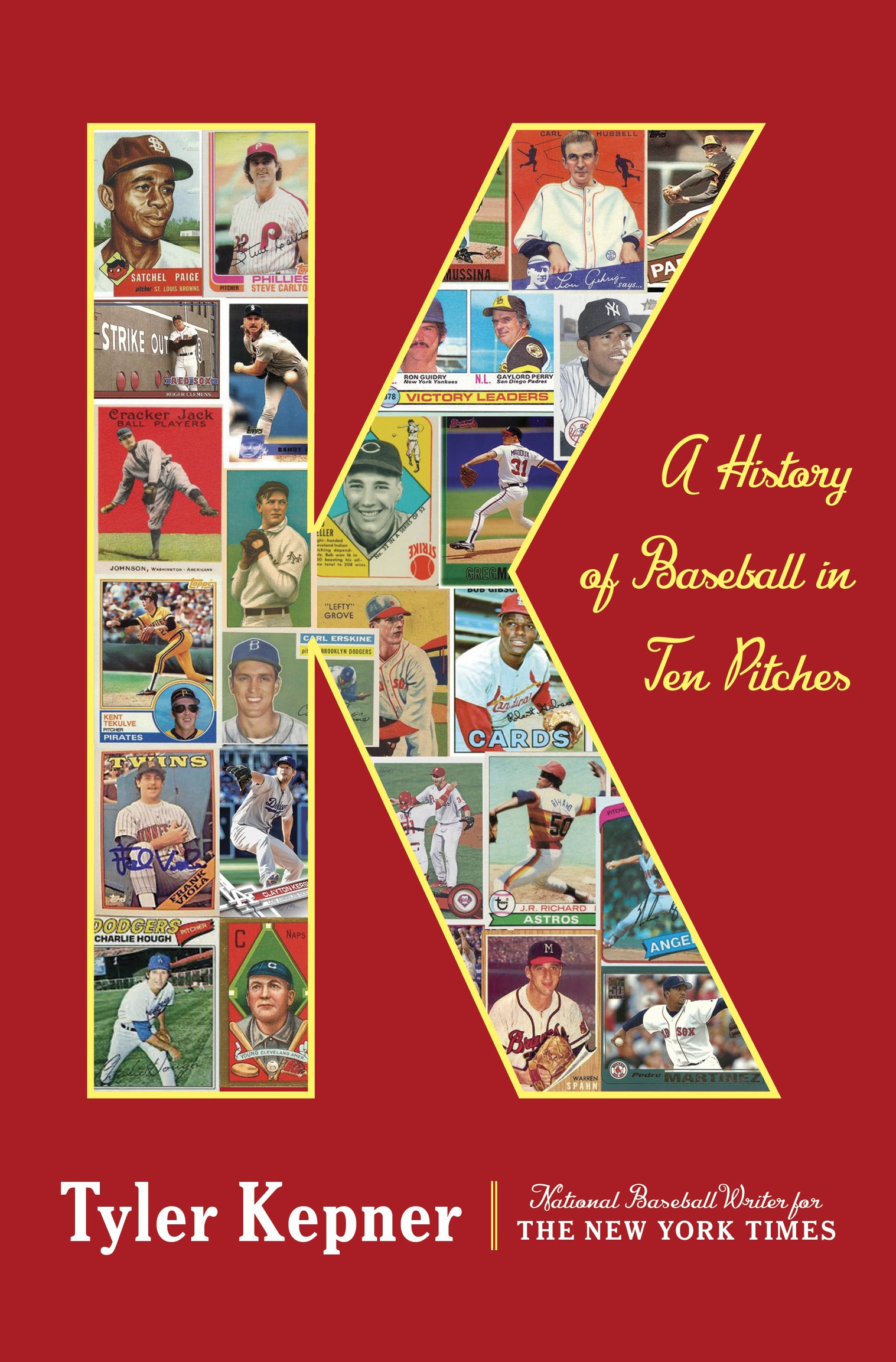

Names: Kepner, Tyler (Baseball writer), author.

Title: K : a history of baseball in ten pitches / Tyler Kepner.

Description: First edition. | New York : Doubleday, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018016158 | ISBN 9780385541015 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780385541022 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Pitching (Baseball) | Pitchers (Baseball) | BaseballUnited StatesHistory.

Classification: LCC GV871 .K46 2018 | DDC 796.357/22dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018016158

Introduction

The kid hung in there as a rookie for the Mets: 11 wins, five losses, a 4.04 earned run average, and 170 strikeouts. But the next year he struggled, and then he got hurt, and soon he was traded to the As and the Twins. Finally he landed with his hometown team, the Phillies, where he stayed for many years, except for one season with the Indians.

He retired with a record of 350182, for a .658 winning percentage. He won five Cy Young Awards, made eight All-Star teams, and struck out 4,819. He was clearly one of the greatest pitchers in baseball history.

This was my life plan in 1986. I was eleven, the oldest a kid can be before reality invades his dreams. I can still throw strikes reliably for the New York media team in our annual games against Boston, and I can spin a loopy little curveball. My arm is never sore, because I dont throw hard and never have.

Before my lack of speed mattered, though, I believed in that handwritten stat sheet. I found it in a notebook a few years ago, in a box at my parents house. By then I was deep into this project, exploring the history and stories behind every pitch, from Christy Mathewsons fadeaway to Clayton Kershaws slider. Seeing my scribbles through the prism of actual history, it struck me that, for some pitchers, real life surpassed my wildest ambitions.

In my childhood baseball fantasy, where I could do anything I wanted, I still won fewer games than Greg Maddux. I had fewer strikeouts than Nolan Ryan, a lower winning percentage than Roy Halladay, fewer All-Star selections than Randy Johnson, fewer Cy Young Awards than Roger Clemens. I spoke with all of them, and hundreds more, for this book. I wanted to know how the masters did what they did, how they learned and applied their best pitches.

Stardom is at their fingertips, literally. Thats the mystery and the madness of the craft. Even the slightest adjustment of a pitchers fingers can turn an ordinary pitch into a major league weapon. If your body and brain can withstand all the failure, youd be foolish to ever quit the job.

The pitcher is the planner, the initiator of action. The hitter can only react. If the pitcher, any pitcher, finds a way to disrupt that reaction, he can win. You need a little luck and relentless curiosity.

By watching baseball up close for so long, and getting to know the men who play it, I can see that I was never like them. My fingers move better on a laptop than they do on a baseball, and Im lucky I found a skill that allows me to move within their world. But I still wish that my younger self had recognized the baseball for the amazing plaything it is, diving and darting and sailing and sinking, with no instruction manual.

In a different Pennsylvania town in the 1980s, another right-hander got it. Mike Mussina grew up in Montoursville, high in the mountains near Williamsport. On cold days he would throw against a cinder-block wall in his basement from about 30 feet away, under a dropped ceiling about six feet, eight inches high. He liked to experiment, and while he couldnt come up with much, he knew what he was missing and how he could find it.

Listen, I didnt leave high school with a fastball, curveball, slider, change, sinkerI had a fastball and a lazy curveball, that was it, Mussina told me in the summer of 2016, over lunch at Johnsons Caf in Montoursville, where he still lives. I came from small-town America. I didnt see anybody else that did anything that I wanted to be able to do. But when I got to college and got to pro ball, now theres other guys out thereMan, thats a pretty good slider, I wonder how he does that? Thats a pretty good curveball, Id love to be able to do that. And so youre looking at other people, youre stealing ideas and seeing if you can do it.

The Orioles drafted Mussina in the twentieth round out of high school, in 1987, but he wanted to learn more, on and off the mound. He hates to travel but chose Stanford University and graduated in three years. The Orioles chose him again in 1990, this time in the first round, and the next year he was in the majors. He stayed for 18 seasons by constantly evolving.

Mussina doubts that many pitchers will last as long as he did, because theres less incentive to innovate. Pitchers throw harder, but theyre not trained or expected to work deep into games. If they were, he believes, theyd have to develop more pitches to keep the same hitters guessing. Then, as their best stuff fades with age, theyd have other pitches to use.

If a starting pitcher does his job, Mussina believes, he should win half his starts. That was his logic long before he finished with 270 victories in 536 starts. But theres a catch: the quality of a pitchers stuff will vary from game to game. In a few starts it will be crisp; in a few others it will be flat. Most of the time, hell have just enough to compete.

What made Mussina great, his peers believed, is that he always had so many options, so many different pitches to grind his way through a start when he wasnt at his best. This is how he described his thought process:

Boy, theres so many variables involved in the equation that you cant even discuss it, almost, he said, then does so at length. Its not like theres nobody on base every timetheres guys in scoring position, nobody out, crowds going crazy. You think, OK, I screwed up, we cant go with A. Whats B, whats C, whats D?

Whos hitting? Is he hot or cold? Where are the base runners? Whats the situation? Where are we in the game? Are we on the road? Are we at home? Is it nighttime? Is it daytime? What has he done the other two at-bats? Lets say its the seventh inning. Where hes at in the box? Howd he look taking that pitch, or howd he look fouling that pitch off?

Theres all these things going on in your head. And then you take in all this outside input and you say to yourself, Yeahbut I dont feel good with that pitch. Because your brain tells you, Look, you should throw this, but I havent thrown one of those for a strike in four innings. Eventually you just have to have enough balls to say, Screw it, Ive got to do it the way I should do it, and whatever happens, happens. I cant just throw fastballs because he knows I dont have a good enough changeup today, or he knows I dont feel good with my slider today. He doesnt