Contents

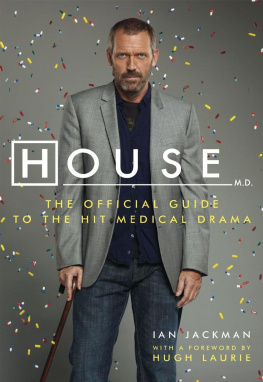

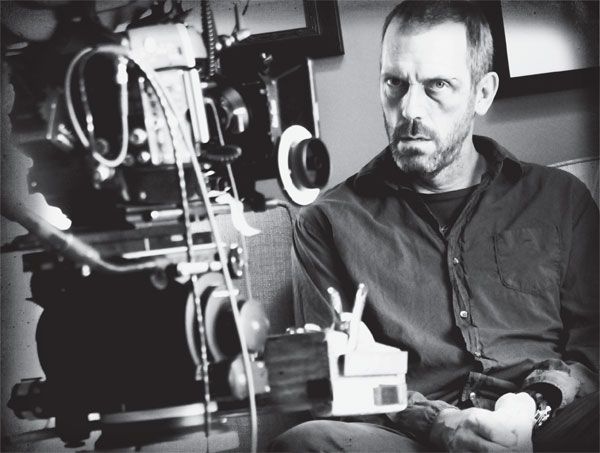

by Hugh Laurie

One Out of One-Three-One

The Start Line: Creating the Show

What If Michael Caine Played Houses Father? Writing House

/ Jennifer Morrison

Eight-Day Weeks: Making the Show, Part I

/ Jesse Spencer

Fourteen-Hour Days: Making the Show, Part II

/ Omar Epps

City of Actors: The Casting Process

/ Olivia Wilde

If Its Happened Once: The Odd Medicine of House

Inside Dave Matthewss Head: How to Fake a Medical Procedure

/ Peter Jacobson

Sets and Stages: Designing and Building House

East Coast, L.A.: The Look of House

/ Lisa Edelstein

Faking It for Real: Props and Special Effects

Making It On-Screen: Visual Effects and Editing

/ Robert Sean Leonard

Everybody Lies: The Dark Matter in the Universe, Part I

Questions Without Answers: The Dark Matter in the Universe, Part II

/ Hugh Laurie

The Episodes

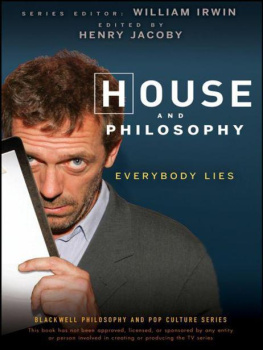

This is not only a foreword to a book but also an afterword to a large chunk of my life.

As I write, in 2010, its more than a tenth: for Jennifer Morrison and Jesse Spencer, bless their creamy complexions, its a fifth. I think its time for an explanation, and one of these old ink-and-paper type deals seems a good spot for it.

I was in a Starbucks once and overheard a woman say to her companion: I had a very interesting blueberry muffin yesterday. At the time, I was struck by her descriptor, interesting. It interested me. There were, and still are, plenty of adjectives available to describe a blueberry muffingood, bad, stale, crumbly, kosher, laced with LSD, or shaped like Richard Nixon, among othersbut interesting? It mystified me. Now, looking back, I think I know what she meant.

Before sunrise on most mornings of the last six yearslets say a thousand mornings, give or takeI have presented myself at the Fox Studio Lot in Los Angeles, a tiny principality on Pico Boulevard with its own police force, fire department, courtiers, peasants, stalwarts, and thieves. It has no established religion, but there is a giant bust of Rupert Murdoch in the central square, about two hundred feet tall, made from the bones of fallen enemies. (I might have imagined this.) Here, on stages 10, 11, 14, and 15, I have immersed myself in a fictional character, in a fictional place, in a fictional world, with an hour for lunch. My experience has been so weirdly shrink-wrapped that I couldnt even tell you what happens on stages 12 and 13, much less the outside world. Come to think of it, I dont even know where 12 and 13 are. Like hotel floors, maybe there is no 13? I know little of Californian weather, or which party is in power, or what the chances are that this hip-hop thing will catch on. Ive used metal cutlery about a dozen times since I got here.

Its been interesting, all right, but not in the way you might expect. The interest has come not from the breadth of the experience but the narrowness; the exclusion of all thought outside the immediate word, blink, breath, momenta moment that has far exceeded its normal duties, eventually stretching to a full six years and thereby risking the loss of its Momentary credentials.

But look, Im getting ahead of myself. Lets go back (if you ever catch me using the word rewind to mean anything other than rewind, I want you to shoot me, dead) to see how all this works.

An Englishman is summoned to Los Angeles. On the strength of a scratchy piece of video tape, he has apparently put himself in contention for a major television role. To advance to the finals, he must jump through hoops, kiss rings, and swear oathsall of which he does, and gladly. He is chosen. He travels to Vancouver, city ofI dont knowbuildings, and there he makes a one hour show, which he lays at the feet of the Gods. The Gods show it to a focus group. It scores highly enough to earn thirteen episodes. The Englishman packs a few shirts, kisses his family good-bye, and flies to Los Angeles. (He emphatically does not jet into Los Angeles as the British tabloids would have it, as if everyone else travels in steam-powered Dakotasbut wait, if I start on the tabloids, well never get out of these parentheticals.)

His expectations at this point are low. He knows that American television is a fiercely competitive arena, and that one hour dramas follow the same actuarial arc as spermatozoagushing toward the giant Nielsen ovum in a spasm of excitement, a few moments of frantic wriggling, then oblivion. And yet, miraculously, the show survives those first weeks, grows stronger, gathers momentum, until its careering, tumbling downhill, and the Englishmans suspenders are trapped in the door and his little legs are scrambling to keep up. Time disobeys its own naturespeeds up, slows down, bends, goes sidewaysthe days become windowless and weird, filming stories that arent real mixed up with photo shoots, red carpets, and talk shows that are even less so. The result, inevitably, is madness. Late one night the Englishman is found wandering the Pacific Coast Highway, naked, carrying a .45, and reciting the Psalm 23.

His name was Ronald Pettigrew and the show was, of course, Wetly Flows the Mississippi . It ran for two seasons on the Trump Network.

Although I havent taken it quite as hard as the Pettigrewster, there have certainly been times when Ive found it intense. Has it been as intense as fighting in Afghanistan or stealing a base against the Yankees (whatever that means and whoever they are) or running a successful brothel? Ive no way of knowing. Some of you may be thinking come on, its only a television show and thats truein the sense that you can attach the word only to any human event, as long as youre calibrated correctly. Nuclear Armageddon will only lead to the end of the human race, a geologist or astrophysicist might say.

But heres the paradox: If those of us who work on House had ever behaved as if it were only a television show, then it wouldnt be a television show. It would be a canceled television show. An ex-television show. Like most people in the entertainment business, we are professionally disproportionate. Intensity exists in the mind, as Marcus Aurelius might have said if you translated him badly, and when disproportionate people decide that a thing is intense, and devote all their physical and mental energies to it, then it becomes so. Well, that is what we did with House , for better or worse. It may seem comical to some; but I hope the Some dont live in glass houses, because those things are ridiculous. The heating bills alone.

But hard work, on its own, doesnt explain why House has become the most watched TV show on the planet. (This is not my claim: I read it in a trade journal recently, and have no idea how the writer arrived at his conclusion. I dont plan on finding out, either.) There has to be something else. Of course, one could say that the show is more than the sum of its parts, but thats true of almost everything outside the field of pure mathematics. Try driving to work in the pile of parts that make up a Honda Civic. One could say that Houses aversion to the genteel, the euphemistic, gives an older audience some relief from the mealy-mouthed political correctness of our time; you could also say that he appeals to a younger crowd because he is anti-authoritarian, which is how young people like to think of themselves, but very rarely are. On top of that, House is a healer, a fixer of problems, a saviornot usually an unattractive quality. All of these things may have contributed in some way to the shows survival into baggy middle age. But, for my money, its the jokes.