The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Ptrus and Ptrus. This story is for you.

This is a true story, though some names and details have been changed or withheld.

Uncertainty hung over the Place de Bordeaux in the early spring of 2009.

Jean-Pierre Rousseau hoped the First Growth estates would release their prices early, setting the tone and tempo for that years sales campaign. During a bullish year, the five most prestigious Bordeaux chteauxknown as the First Growthssat back and waited, calculating exactly how high the prices for their wines might go, dragging out the campaign into late June, when everyone would rather be at the beach. During a bad yearand the campaign for the 2008 vintage was shaping up to be particularly badthe merchants hoped the First Growths would release their prices early, because there was no campaign to speak of, and the pricing hierarchy for Bordeauxs wines was set from the top down. This year, however, banks were collapsing in the United States and Europe and the economy was in free fall; there was really no telling what the First Growths would do.

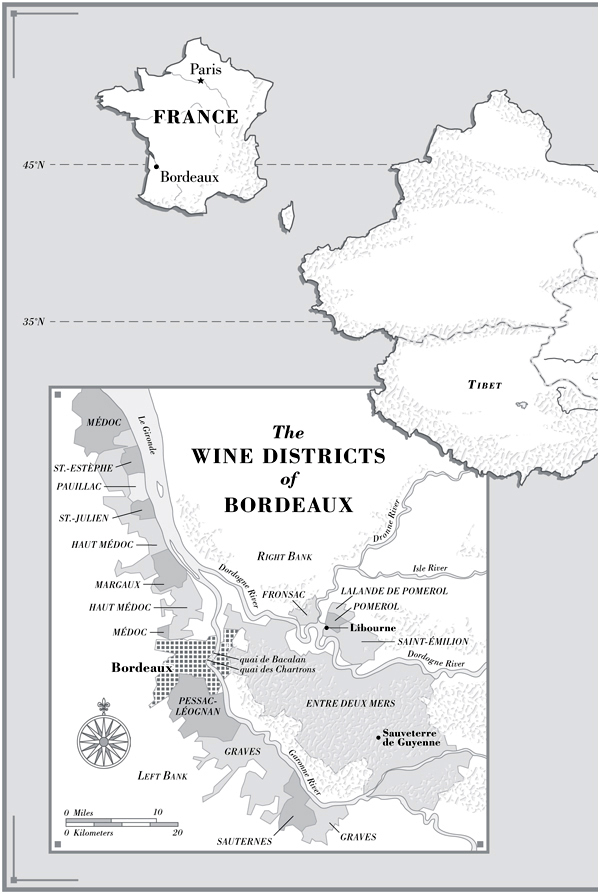

The Place de Bordeaux isnt a square or a leafy promenade or even a physical building; it is the virtual exchange through which Bordeauxs wines have been sold for centuries, and Rousseau was a ngociant , which meant he was a wholesale wine merchant. As was the custom, he bought wine from the chteaux through a licensed intermediary, called a courtier , who brokered the deals. Courtiers were famously tight-lipped, taking 2 percent on every transaction for settling the price and amount of winecalled the allocation granted by a winegrower to a ngociant, and guaranteeing the quality and provenance of the wine. The arms-length nature of the deals buffered some of the natural suspicion and animosity between growers and ngociants. For as long as they had been trading, more than eight hundred years, the ngociants tried to drive down prices, and the growers tried to push them up. The ngociants needed lower prices to ensure that they could sell the wines to their clients around the world without losing money. Some vintages might be sold instantly, but others might not find a customer until they were in bottles and ready to ship, two years down the line. And some might not sell even then.

In the spring of 2009, the courtiers and ngociants fervently hoped they were not going down in flames. For the past several months, the market for Bordeaux wine had been collapsing, a casualty of the global economic crisis. Importers couldnt place orders because their credit lines were frozen. Restaurants closed their doors for lack of customers. Collectors, hit hard for cash, emptied the contents of their cellars at fire-sale prices. And for the first time since the Asian banking crisis of the late 1990s, canceled orders were flooding into the Place de Bordeaux. In a matter of days, the chteaux would offer six hundred million bottles of their new vintage for sale, and customers were begging off. The mood on the Place de Bordeaux was morose.

Not a customer in front of us , thought Rousseau.

He knew how much he could spend, and he knew that many of the smaller ngociants didnt have the cash reserves to buy wine they couldnt immediately resell.

When the market was like this, the larger ngociantsCompagnie des Vins de Bordeaux et de la Gironde (CVBG), Maison Ginestet, Maison Joanne, Maison Schrder & Schler, and Rousseaus own firm, Divaincreased their allocations of certain wines, so that when the market turned, and it would turn eventually, they would control large quantities of the most sought-after labels. There is always someone trying to replace you, said Rousseau. Its so difficult to get allocations of the top chteaux that no one wants to leave the stage.

It was a crapshoot, but no one stepped onto the Place de Bordeaux if he didnt like to gamble.

Late on the afternoon of April 16, 2009, one of the five First Growth estates, Chteau Lafite Rothschild, released its 2008 vintage at 130 ($166) per bottle. For any ngociant who still had money, this was a very good deal indeed: it was 30 percent cheaper than any other available Lafite vintage. Other chteaux followed suit, dropping their prices in the face of the weak market. But the gesture was not enough for the American distribution giant Chteau & Estate Wines. For the first time in thirty-five years, C&E refused its Bordeaux allocations, leaving a huge quantity of the worlds finest wines unwanted and unsold. The betrayal reverberated across the region.

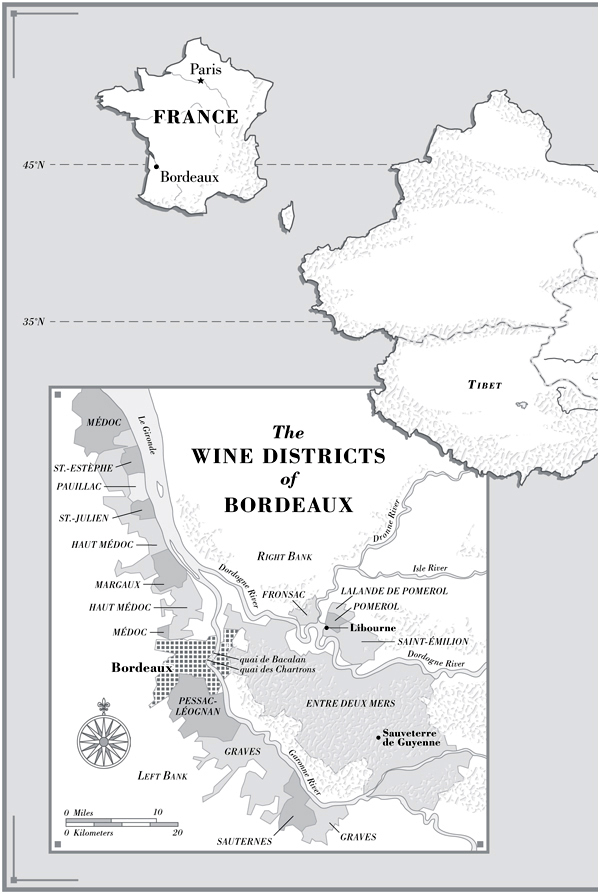

At Divas offices at 34 quai de Bacalan, Rousseau looked on with a mix of resignation, satisfaction, and curiosity. It had been a predictably feeble campaign, but he had taken advantage of the lower prices and the weakness of certain of his competitors to increase his allocations. The wines would not be bottled for another eighteen months, but he felt he could hold on until the market turned. And he hadnt been forced to finance as much of his purchases out of his own pocket as he had feared. He had already resold some of the wine to regular customers who were weathering the banking crisis, which had helped to reduce his exposure. But it was his client in Hong Kong that had jumped in with both feet. The percentage of Rousseaus business with that client had doubled. It was extraordinary.

Ive sold 20 percent of the wine to Topsy Trading, he said with a combination of relief and astonishment.

The impact on Bordeaux would be immediate if slight, a rivulet sprung from a barrel.

* * *

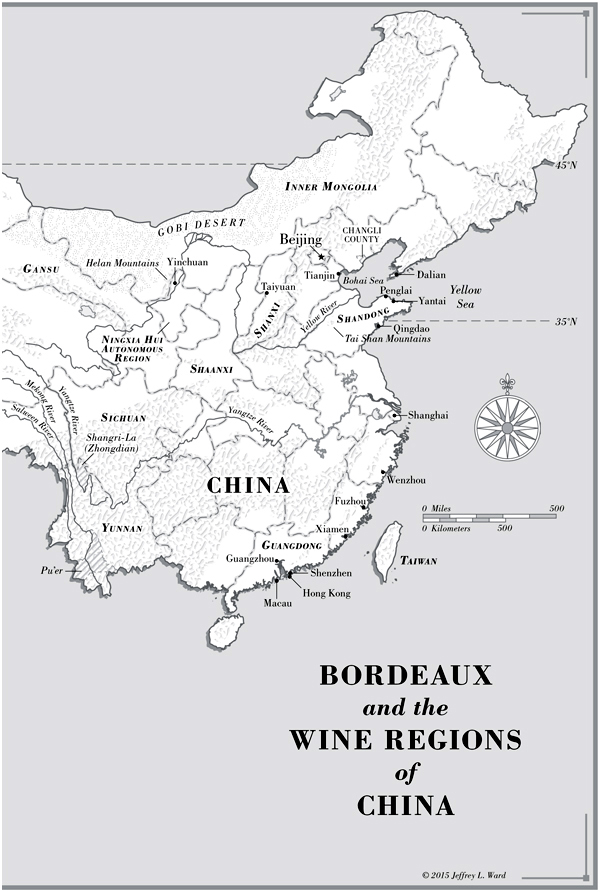

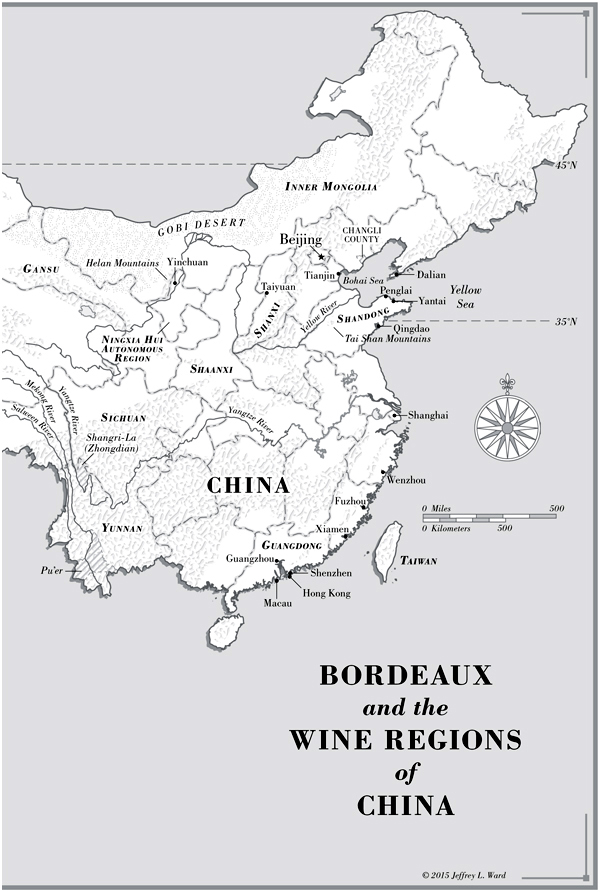

Topsy Trading is a Hong Kongbased wine importer owned by a legendary local merchant named Thomas Yip. Yips family had fled Sichuan Province for Hong Kong shortly after the Communists took control of China in 1949. The Yips were entrepreneurs, and by the time Thomas was in his twenties in the 1960s, he was running his own travel business. When his wife pressured him to find a more stable income, he took a job in the warehouse of Caldbeck MacGregor & Company, the leading wine and spirits importer in East Asia.

From its premises at 4 Foochow Road, just off the Bund in Shanghai, Caldbeck MacGregor had dominated the market for fine wine in that citys international settlement before the revolution. After 1949, the companys Hong Kong office slaked the thirst of the British colonys many diplomats and businessmen. Yip was quickly promoted to controller of the companys wine division, where he thrived, building a network of contacts in the cellars of Europe and in Hong Kongs hotels, restaurants, and duty-free shops.

Within a few years, the Hong Kong and Shanghai Hotels group, informally known as the Peninsula Hotels group, recruited Yip to supply wine to its hotels, and when he proved good at it, Peninsula branched out and started supplying wine to other hotels as well as restaurants. In 1976, the company created Lucullus, a wine and food outfit, putting Yip in charge.

![Jon Bonné - The New French Wine [Two-Book Boxed Set]: Redefining the Worlds Greatest Wine Culture](/uploads/posts/book/443558/thumbs/jon-bonn-the-new-french-wine-two-book-boxed.jpg)