For Ryan, Henri, and Margot

Contents

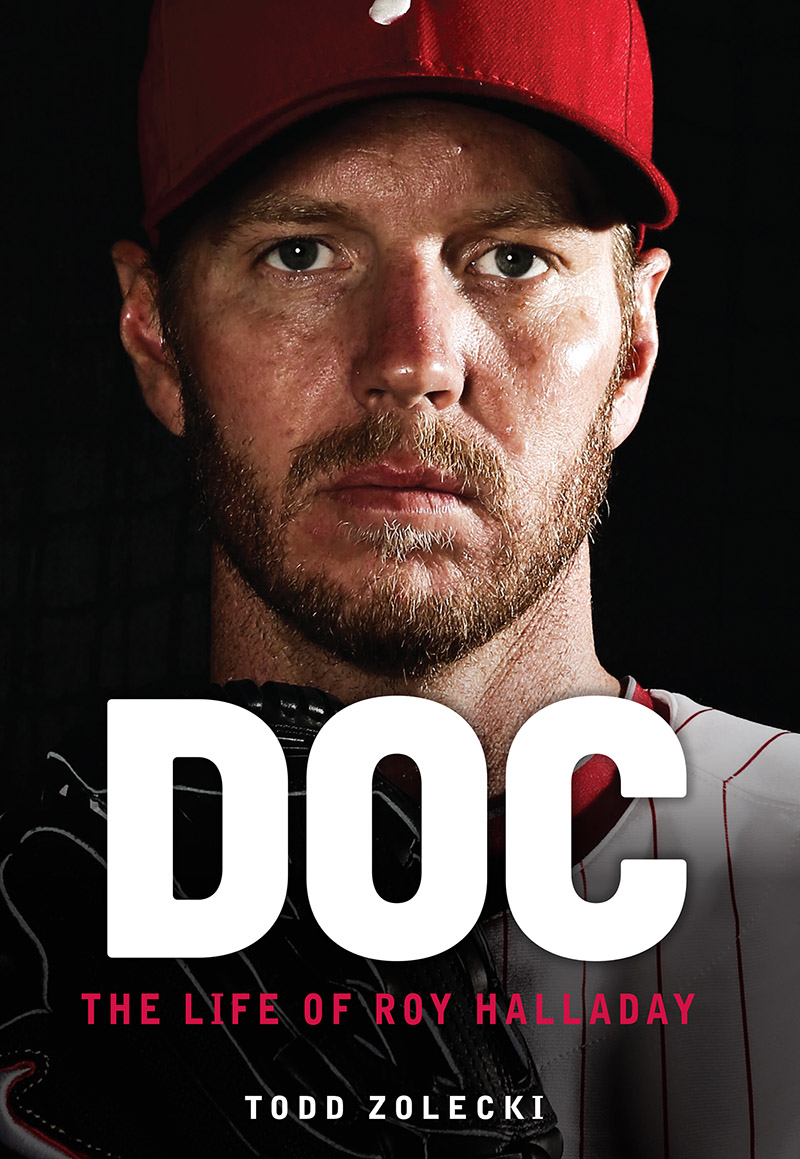

1. Doctober

Roy Halladays eyes never left the TV.

It was October 6, 2010, a little more than an hour before Game 1 of the National League Division Series against the Cincinnati Reds, and Halladay pedaled a stationary bike alone in a room inside the Philadelphia Phillies clubhouse at Citizens Bank Park. Halladays routine dictated everything on game days, which meant he rode a bike a little more than an hour before every start. It did not matter if it was a midsummer game against the worst team in baseball or the first postseason game of his storied career. The routine never changed.

Phillies center fielder Shane Victorino walked past Halladay on his way to see the teams chiropractor. He looked at the Phillies ace, but Halladays eyes never moved.

Any human being, when somebody walks by them, that close to them, they will give some kind of look, Victorino said. Its like I wasnt even in the room.

Halladay was more machine than human on the days he pitched. Everybody knew this. Nobody said hello to him. Nobody approached him. Nobody punctured his cocoon of preparation.

Victorino looked at the TV. He knew the man on the screen commanding Halladays attention. Texas Rangers ace Cliff Lee was carving up the Tampa Bay Rays in Game 1 of the American League Division Series at Tropicana Field. Lee became an instant Philadelphia folk hero in 2009 when he joined the Phillies in July, then went 40 with a 1.56 ERA in five postseason starts, including an unforgettable complete game against the New York Yankees in Game 1 of the World Series at Yankee Stadium. Phillies fans loved Lee, but the team traded him to the Seattle Mariners a couple months later, at the same time it announced it acquired Halladay from the Toronto Blue Jays.

Halladay waited a lifetime for his postseason moment. He trained to be a pitcher since childhood. He was a first-round draft pick in 1995. He came within one out of a no-hitter in his second big league start in 1998. But after historic struggles put his career in jeopardy in 2001, he re-engineered his pitching mechanics and rewired his brain in a top-down physical and mental rebuild. Halladay remade himself into arguably the greatest pitcher of his generation, establishing an unparalleled work ethic and legendary mental approach. But after failing to sniff the postseason for more than a decade in Toronto, the man nicknamed Doc, after the legendary gunslinger Doc Holliday, orchestrated a trade to Philadelphia. And now, a little more than an hour before he threw his first postseason pitch in front of a sellout crowd, he watched the Phillies 2009 postseason hero strike out 10 batters and allow one run in seven innings in a victory over Tampa Bay.

I think Roy was looking at Cliff going, Really? Victorino said.

A feeling overcame Victorino.

Docs going to go out and do something special, he thought.

Halladay went to see Phillies strength and conditioning coordinator Dong Lien. It was about 4:00 pm , which meant Halladay was right on schedule for the 5:08 pm first pitch. Lien stretched Halladays legs about an hour before every game. The two were close, but Lien never talked to his friend on game days. He respected his process too much. Not that a conversation was possible anyway. Halladay wore earphones before he pitched. Sometimes he listened to nothing, wearing them to discourage interruptions. Sometimes he listened to Harvey Dorfmans career-saving The Mental ABCs of Pitching, which he had on his iPhone only because he paid somebody to read and record the book in studio. But Halladay mostly listened to music. He liked Enya. Her song Only Time regularly played when Lien stretched him. It might surprise people to know that, but Halladay, who stood 6-foot-6 and intimidated opponents, umpires, managers, and even teammates with a stare, did not pitch on emotion. He pitched in complete control of his thoughts and feelings.

Halladay learned a long time ago that negative thoughts lead to negative results, so he trained his mind to behave differently. He stopped thinking about the big picture and what might happen if he threw a bad pitch. He stopped worrying about what people might think if he failed. Dorfman taught him to focus on the task at hand, which meant the next pitch and only the next pitch. Doc struggled toward the end of the regular season, posting a 4.32 ERA in six starts before he tossed a shutout to clinch the Phillies fourth consecutive National League East title. Halladays conversations with Dorfman before the division-clinching game recentered him for the postseason.

I had so many nights when I sat up thinking what it would be like, how I would do, how would I handle it, Halladay said. I really went back to the basics. I thought about all of the things that have created this success for me; the thoughts of one pitch at a time, not worry about what will happen or what did happen, just concentrating on the moment. And had I not had Harvey, I wouldnt have done that. I wouldve been thinking, Crap, playoffs are coming up. I have one start left. If I dont pitch well here then no one is going to have confidence in me. I wont have confidence in me. And thats just not the way I approached it. But I wouldve never done that without Harvey.

So many guys talk about getting there and wait a long time to get there and then, when they do, they soil themselves, Dorfman said.

* * *

Halladay had nine days to prepare for Game 1, which he considered bad news for the Reds because they would not outwork him.

Theres no way, he said. Im going to know every single thing about every hitter. So going into that game I was as confident as Id ever been. Even though I had all these feelings underneath, I knew as soon as I stepped on the mound they would go away.

Halladay met Phillies catcher Carlos Ruiz and pitching coach Rich Dubee in the Phillies dugout at 4:30 pm. Halladay always met them in the dugout at half past the hour, whether the game started at 1:00, 5:00, 7:00, or 8:00. They walked to the outfield together. Halladay continued up the bullpen steps alone. He put his glove and jacket down, returned to the field and jogged to warm up his body. He returned to the bullpen to use the bathroom. Doc always peed after he ran.

Every time , Dubee said. I dont know how many starts he made with us, but every time he had to go up and pee because he was so hydrated. Nothing was left to chance.

Halladay grabbed his glove and returned to the field. He stretched his arm and shoulder against the fence. He long tossed with Ruiz from 100 to 110 feet.

Halladay, Ruiz, and Dubee went to the bullpen to warm up. Doc threw 20 pitches from the windup and 20 pitches from the stretch. He threw sinkers to both sides of the plate, cutters to both sides of the plate, changeups to both sides of the plate, and curveballs. He finished from the windup with one sinker to his arm side (the right side of the plate) and one sinker to his glove side (the left side of the plate). The routine never changed. If he missed cutters to his glove side, he moved on. He knew that warmup pitches did not predict his performance in the game.

I think a lot of that had to do with Harvey, Dubee said. Harvey was a great teacher. He was very thorough and disciplined about having routines, about being so locked in that you had a routine and nothing got in your way. It was physically, it was preparation, it was mentally the focus before each pitch.

Halladays four greatest concerns in the Reds lineup were: Brandon Phillips, Joey Votto, Jay Bruce, and Scott Rolen. Halladay studied hitters so thoroughly that he felt he knew what they were thinking. He never could figure out Phillips, though. Phillips baffled him. Votto was one of the smartest hitters in baseball; he thought along with the pitcher. Halladay considered Bruce a tough out because he changed his approach from time to time. Halladay knew Rolen because they played together in Toronto. Rolen was smart, like Votto, and he liked to get in the pitchers head.