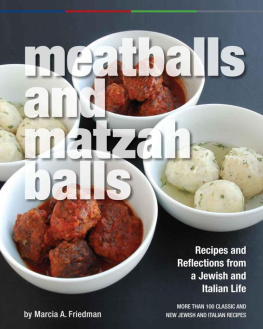

A Kabbalah of Food

A Kabbalah

of Food

Stories,

Teachings,

Recipes

Rabbi Hanoch Hecht

Monkfish Book Publishing Company

Rhinebeck, New York

A Kabbalah of Food: Stories, Teachings, Recipes 2020 by Rabbi Hanoch Hecht

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without the consent of the publisher, except in critical articles or reviews. Contact the publisher for information.

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-948626-31-6

eBook ISBN: 978-1-948626-32-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hecht, Hanoch, author.

Title: A kabbalah of food : stories, teachings, recipes / Rabbi Hanoch

Hecht.

Description: Rhinebeck, NY : Monkfish Book Publishing Company, [2020] |

Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020025996 (print) | LCCN 2020025997 (ebook) | ISBN

9781948626316 (paperback) | ISBN 9781948626323 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Hasidic parables. | Food--Religious aspects--Judaism. |

Hasidim--Legends.

Classification: LCC BM532 .H37 2020 (print) | LCC BM532 (ebook) | DDC

296.7/3--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020025996

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020025997

Cover art: Shabbat Table Michoel Muchnik

Seder plate illustration and author photo Susan Piperato 2020

Book and cover design by Colin Rolfe

Monkfish Book Publishing Company

22 East Market Street, Suite 304

Rhinebeck, NY 12572

(845) 876-4861

monkfishpublishing.com

This book was written in the hope that these stories, teachings, and recipes bring readers closer to observing kashrut properly and to elevating the sparks of godliness within the physical world.

And to Gedalia Dovid and Devorah Shifra, who have taught me the meaning of giving without receiving anything in return.

May Hashem bless you with only open and revealed goodness.

Contents

Introduction

Nothing is more central to Jewish life than food and storytelling. In fact, in Judaism, food is an integral part of religious practice, from observing the many laws of keeping kosher to the ritual preparation and eating of the special foods connected to the many Jewish holidays and Jewish culture.

I have always loved eating foodwho doesnt?!but the way I came to love cooking is another matter. When I was a yeshiva student, I was a bit of a wiseacre. I couldnt refrain from telling jokes in class, sometimes at the expense of my poor teachers. Consequently, they often asked me to leave the classroom. They assumed I would hang out in the hallways and get caught by the principal, who would then send me home so my parents would have the opportunity to deal with me. But since I didnt relish the thought of that, I would instead head to the cafeteria to see Mrs. Kraus, a wonderful elderly lady who was our schools cook. In return for my help with the chores, Mrs. Kraus would share some of the secrets of her preparations. Thus, I not only avoided the wrath of my parents, but I also learned early in life to love cooking and being in the kitchen.

When I was young, I also learned to love storytelling. In a Chassidic home, storytelling is a way of life. The stories come from our elders own lives or the Hebrew Bibleor they are mystical, folktale-like accounts of events in the lives of the Chassidic masters and their followers. Through all these stories, children learn the Jewish principles and guidelines, and about morals. Of course, you can also teach children these things in other ways, but if you want to make a real impression, warm their hearts and create within them a love and caring for certain subjects, theres no better way than with a story. Thats especially true if the stories are entertaining, heartfelt, humorous, or humblinglike the ones told in my home. For example, my grandfather, bless his memory, used to tell us a story about seeing his childhood friend again at his thirtieth-year high school reunion.

So, what do you do for a living? my grandfathers friend asked him.

Im a rabbi, my grandfather replied.

Oh, his friend said, surprised. But I thought you wanted to be an attorney.

My grandfather smiled, shaking his head. I did, he said, but then I realized its easier to preach than it is to practice.

With that story, my grandfather was teaching us about the difference between practicing ones faith and talking about it. He also used to teach us about humility through stories like this one:

Once there was a young man who was the son of a rabbi and also became a rabbi himself. On the day of the young mans ordination, his father pulled him aside and told him, Son, when you go to Heaven, you wont see any rabbis there, but when you go to hell, there you will see many.

That was, of course, a memorable way for my grandfather to show us that being a rabbi doesnt necessarily guarantee a persons holiness. Significantly, not only was my grandfather a rabbi, but so was my father, and so am I. Indeed, I come from a large family with many rabbis, both here in the United States and abroad.

In Hebrew, the word for action is maaseh . As our rabbis say, Ha Maaseh, hu haikar : Talk is cheap; action is what matters. Talking and preaching about giving charity is nice, but it means nothing. Youve actually got to give charity. In Yiddish, the similar word masaleh means story. Theres a saying, Ha Masaleh, hu haikar : The story itself is the fundamental point. If youre trying to have a lasting effect on your listeners, inspiring them to action, then storytelling is the way.

The word kabbalah means to receive. Its a tradition that began with the giving of the Torah at Mount Sinai. At that awesome event, all the living men, women, and children of the Jewish faith were present, along with the souls of every future generation of Jews, and they received the Torah along with the Kabbalah, which is the Torahs mystical part. At first, only people of great spiritual and intellectual caliber could study Kabbalah, and only in secret; it was not until the sixteenth century that Rabbi Isaac Luria, known as the Arizal, the lion, advocated for the masses to begin studying the Torahs mystical aspects. In fact, modern-day Kabbalah begins with the Arizal, who is a very interesting figure. As a young man, he spent many years living in a hut on a riverbank, delving into the secrets of the Torah and reading mystical books like the Zohar and the Sefer Yetzirah. In this way, he learned the magical aspect of Kabbalah and how to manipulate the physical world, and he used these secrets to strengthen Judaism and teach people to connect to God at a deeper level.

Initially, certain guidelines were followed for Kabbalah study. One needed to acquire a certain level of maturity as well as an understanding of many of the Torahs other teachings. It was thought that if someone studied the Kabbalah before being ready, he could come up with the wrong understanding of both God and life itself. The Talmud contains a story illustrating this point:

Once there were four rabbis who entered the garden , meaning they underwent a powerful Kabbalistic experience, and each one was affected differently by it. As soon as the first rabbi left the garden, he passed away. His soul couldnt handle such an intense mystical experience and left his body. His soul effectively said, No more! I no longer want the physical world; I only want the glory of God.

The second rabbis body could not handle what he encountered in the garden, and he emerged completely insane.