All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Harmony Books, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Harmony Books is a registered trademark, and the Circle colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Smith, B. (Barbara), 1949

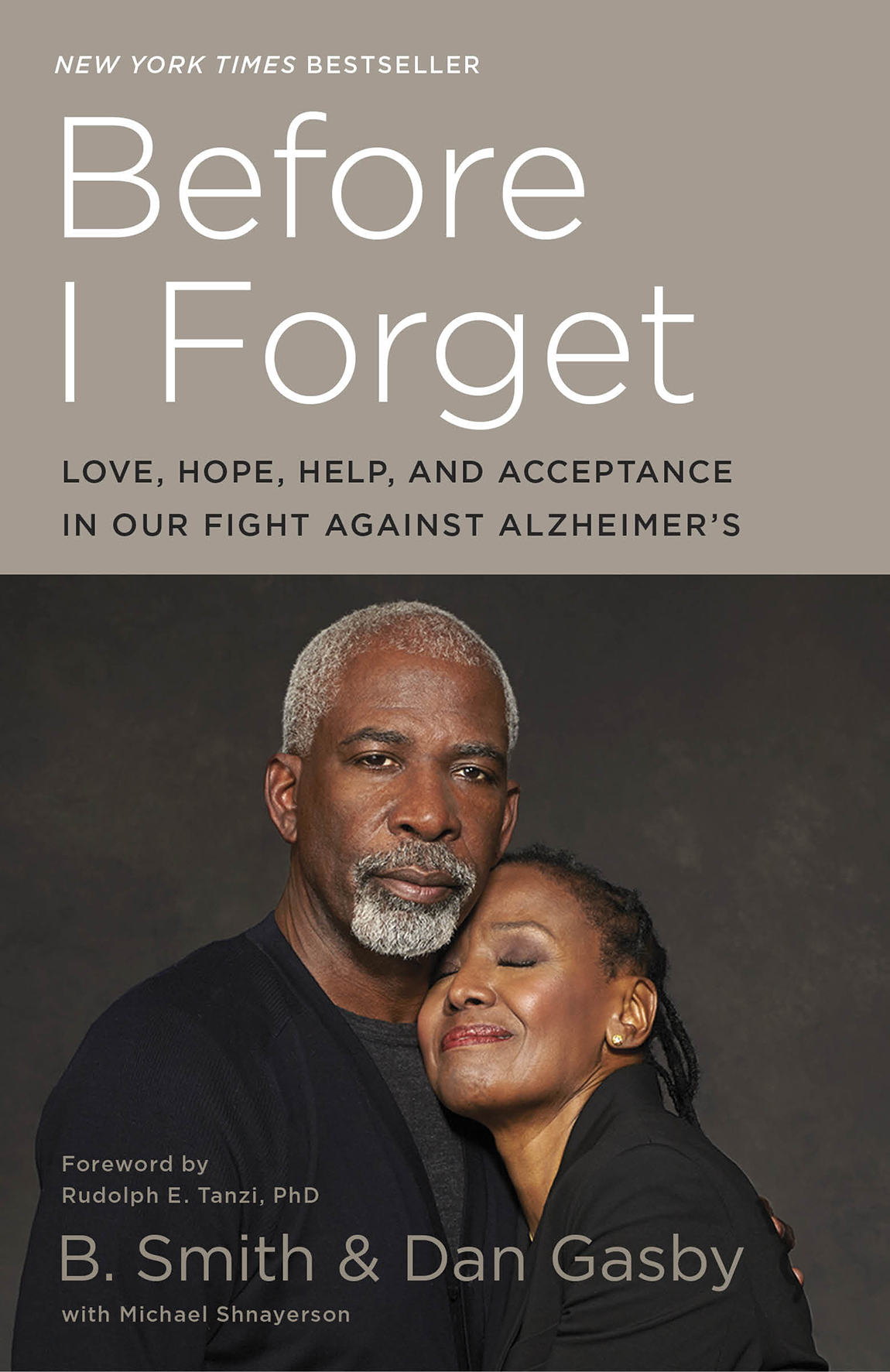

Before I forget / B. Smith and Dan Gasby.First edition.

1. Smith, B. (Barbara), 1949 2. Gasby, Dan. 3. Alzheimers diseaseBiography. 4. Husband and wifeBiography. 5. Alzheimers diseaseFamily relationships. I. Gasby, Dan.

To the men and women of the U.S. Congress who have the power to help spare future generations from the ravages of Alzheimersand to all who will be helped by them.

Foreword

by Rudolph E. Tanzi, PhD

It haunts us with every name we forget: the fear that Alzheimers is in our future.

For many of us, those lapses will be nothing more than the natural aging process. But for an estimated 5.2 million Americans, Alzheimers has taken holdand to most of us in the field, that number is way too low. Millions more die of Alzheimers-provoked causes, from organ failure to pneumonia. Alzheimers is a thief that robs you of your memories, your personality, ultimately of your self. It pulls apart the tapestry of who you are thread by thread, until the tapestry just disappears. Cancer is the Big C, but many now overcome it. With the Big A, to date, not one person has survived.

In one sense, we have modern medicine to blame. At the dawn of the twentieth century, our lifespan was forty-nine years. Most of our forebears who carried Alzheimers-linked genes didnt live long enough to develop the disease. Now many of us live into our eighties: by eighty-five, a third will have Alzheimers and half will be in the earliest stages of the disease. Nearly 75 million baby boomers are heading that way. Already, Medicare and Medicaid are staggering under the costs. I calculate that by 2020, if the federal government fails to take drastic measures, they may reach a tipping point and start to collapse.

Each year, the federal government spends $612 billion on each of the usual suspects: cancer, heart disease, and AIDS. It spends less than $500 million on Alzheimers. Of that, perhaps only $250 million goes to basic research; much of the rest goes to carrying out large-scale clinical trials for drugs that have, so far, without exception, failed. In his 2015 State of the Union speech, President Obama pledged another $50 million for Alzheimers. Unfortunately, its a Band-Aid on a gaping wound.

Why the shocking lack of funding? One reason is that the young tend to protest more loudly and actively than their parents and grandparents. And of those who have Alzheimers, how many are likely to be lobbying in Washington about the loss of their minds? But as I warned last years graduating class at the University of Rhode Island, the young may want to reconsider their lack of interest in Alzheimersfor almost entirely selfish reasons.

Those graduates will likely live to be eighty-five or ninety years old, if not one hundred. That means more of themfar morewill get Alzheimers than cancer or heart disease. They may see it as their aging grandparents problem. In the long run, its theirs. Not only that: they have parents. By their fifties, many of those graduates will hope to have put their own children through college and be spending those later decades traveling the world. No way: not with parents succumbing to Alzheimers. Through gritted teeth, those graduates will be spending their savings on assisted care and nursing homes and hospice care. Even now, Alzheimers is not just a disease of the old. It affects us all, and will do so more deeply within the next decade.

Heres the good news. Alzheimers is probably the most striking example we have among major diseases of a budget-constrained problem. As opposed, that is, to a knowledge-constrained one. We know what we need to do. We have dozens of gene candidates to work on, each one of which can present a new opportunity for drug development. We just lack the money to do that work.

The bad news is that Alzheimers isnt merely under-represented in funding compared with those other diseases. Those genes we need to look at? Together, we in the field have less than 5 percent of the funding we need to pursue their potential. Im more fortunate than most; Ive published nearly five hundred research papers, and my lab gets serious attention from the National Institutes of Health. Younger scientists in less well-known labs struggle for even the most essential funds to continue. Theres so little money in science and research in the United States that more and more students choose not to enter the field. The result: our country faces losing a generation or two of scientists, and all the work they would do. If America does not step up and start funding medical research more seriously, we will rapidly lose our place as a world leader in biomedical discovery. While pharmaceutical companies are needed to bring drugs to the market, the seeds of discovery begin in academic institutions, which depend on federal funding to survive. I am also lucky to be funded by the Cure Alzheimers Fund (http://curealz.org), the most forward-thinking and -looking Alzheimers research foundation in the world, in my opinion.

Yes, we do at last know which way to proceed. After decades of debate about how Alzheimers forms in the human brain, we know what the pathologies are, and how they progress, along with the genes that are responsible. Those genes provoke the creation of amyloid plaques. The plaques then cause so-called tau tangles to form in the surrounding brain cells, eventually to kill those cells. Plaques also cause inflammation, which kills more cells, leading to even more inflammation in a vicious cycle. As our Alzheimers-in-a-Dish studies have shown, the amyloid sets the fire, if you will, and tangles are the fire that spreads throughout the brain; inflammation fans the flames and makes the fire spread that much faster.

Heres something else we know now: the amyloid plaques start building up in the brain at least fifteen years before the disease manifests itself. So we know we have to detect plaques far sooner. Then we must have therapies ready to slow them down, akin to lowering cholesterol, if it is too high, to prevent heart disease.

Nearly all of us will develop at least a few of those plaques, though not all of us will get Alzheimers. Why? More and more, we think inflammation is key. While plaques and tangles may push you up the mountain, it is inflammation that throws you off the cliff. In the process of inflammation, certain immune cells in your brain kill nerve cells in response to the pathology, leading to a massive loss of nerve cells and the neural circuitry needed for learning and memory.

So we have three mantras going forward: early prediction, early detection, and then early prevention. We will use genetics to predict risk, biomarkers and imaging to detect the disease before symptoms, and then steps to prevent the disease from taking root in those with the strongest propensity to develop it.