Contents

Guide

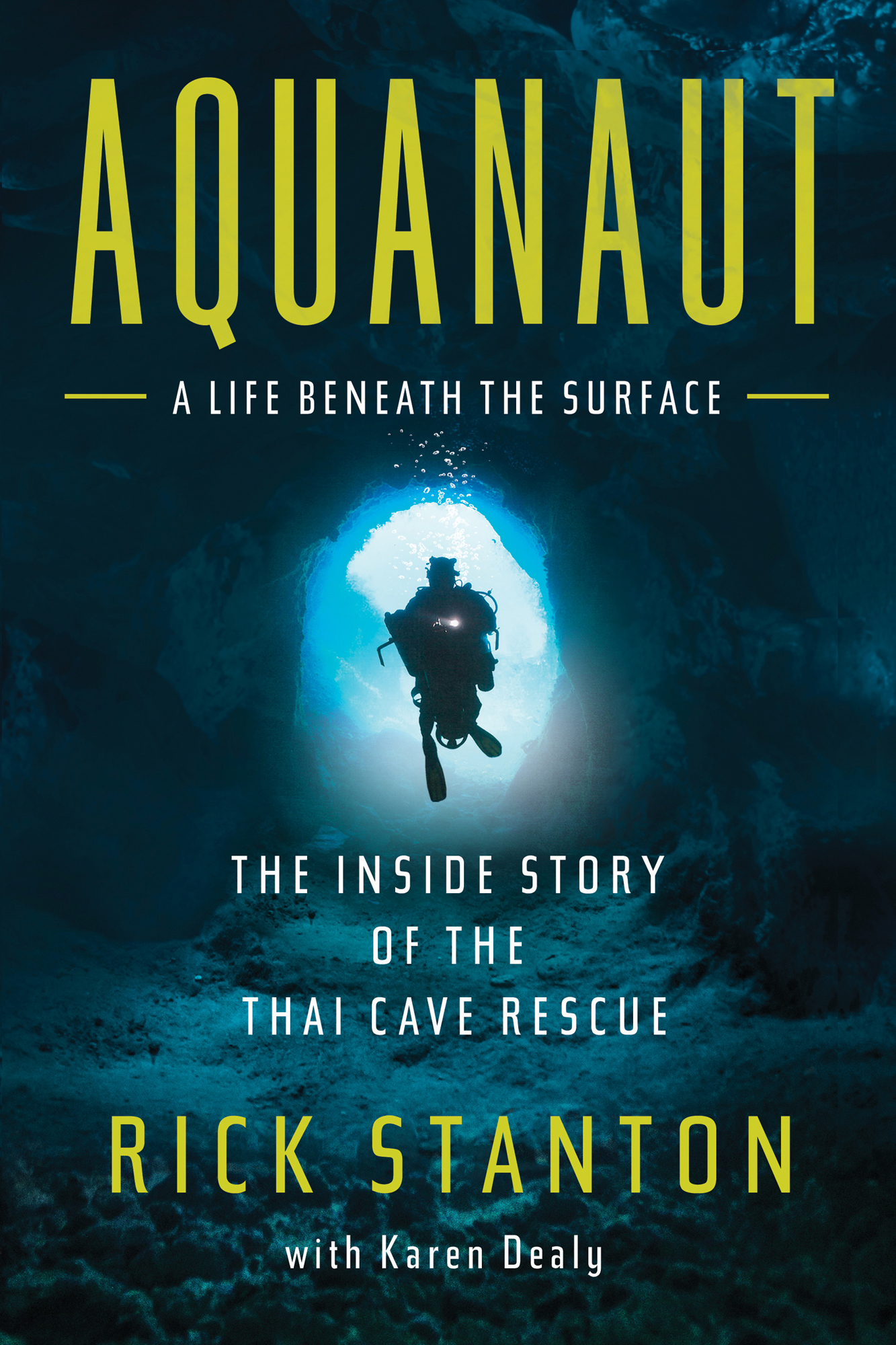

Aquanaut

A Life Beneath the Surface

The Inside Story of the Thai Cave Rescue

Rick Stanton

with Karen Dealy

AQUANAUT

Pegasus Books, Ltd.

148 West 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2022 by Rick Stanton

First Pegasus Books cloth edition January 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-64313-919-7

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-64313-920-3

Jacket design by Faceout Studio, Amanda Hudson

Imagery by Alamy, Getty Images, and Shutterstock

Distributed by Simon & Schuster

www.pegasusbooks.com

My first example of courage, dignity, strength and humanity came from a woman whose diminutive stature and quiet nature did not prevent her from having a profound impact on the lives around her.

Mum.

With one comment made, one night in front of the television, you set my life on its course.

I owe this book, and the stories it contains, to you. I was called to Tham Luang when I was fifty-seven, which was your age when you departed. I wish you could have seen your impact on the person Ive become.

Thank you.

Prologue The End of the Line

Monday, 2 July 2018, Thailand

What could possibly go wrong?

I pulled myself through a tunnel of rock, blindly fighting against an underground river that was flowing deep inside a mountain. The current pushed against me so forcefully that it felt like the water or maybe the mountain itself was trying to keep me out. Thirteen young men had been the last to travel this path before me, and I had gone there to save them.

Although millions around the world were waiting and watching, hoping to hear news of the boys safe discovery, many had already given up hope. (They cant possibly still be alive in there.) In the week since I had flown to Thailand to take part in this search, I had been plagued with thoughts about what I would be finding. I too assumed that the boys were dead, but that was unimportant to me. I stayed there, searching, pushing myself through the cave, because I had to see it through to the end. I had to see for myself.

Maybe I was just looking for an answer so that I could put an end to the searching.

This wasnt the first time Id been sent into a cave to bring out a body, but this was the first time that the ones I was searching for were a group of children. That made a difference that made a better story for the press and the throngs of journalists camped on the mountain just outside served as an unmistakable sign that the world wanted to be given a happy ending.

More important to me than the media, though, were the mothers and families who had not left their posts on that mountain for over a week. I could walk past the cameras and microphones without a glance, but even I couldnt ignore the much smaller huddle of women, whispering prayers and watching us as we walked into the cave that held their sons. I avoided the women, but I knew they were there, and they acted as constant reminders of why I was there.

As the sun shone high in the midday sky on a fateful Saturday in late June, thirteen young men all members of the Wild Boars football team had walked into Tham Luang Nang Non cave, whose opening is on the side of a mountain in the Doi Nang Non range. The team had taken the same path that I am on now, but the way for them had been largely dry and clear. When they had taken this journey, they had moved forward by walking, scrambling and crawling. They had likely been talking and laughing as they went along, perhaps discussing Nights upcoming birthday party, or a recent school exam; perhaps Coach Ek had been reviewing some football moves he had taught them earlier that day in practice. I imagined the sounds of their voices and laughter echoing through the empty chambers, fading into the blackness that surrounded their feeble lights. The solid feeling of sediment beneath their hands and feet would have been reassuring to them as they moved along and encouraged each other onward, scrambling over boulders and crawling on their bellies through the low sections. The journey would have been physical and demanding, an exercise in spirit and solidarity for the team.

Not only were they not afraid, they didnt realize that they should be.

While they were scurrying their way forwards through the cave, with the lighthearted goal of etching their names into the mud at the far end, rain had started falling onto the mountain above them. The boys were nestled within the silence of the cave, protected from the elements and unaware of the danger approaching them, as rain seeped through the layers of rock. The open cave passage provided a clear funnel for the water to flow through, as it had done so many times before, and the cave began to fill. When the team finally turned to make their way out, they found that their playground had drastically changed.

With their exit blocked, the team made an unusual decision. Instead of staying where they were and waiting for rescue, the group turned back into the mountain and moved deeper into the cave. This time they werent chasing an adventure; now they were hoping for survival. By the time the moon had risen above, they were trapped inside with a kilometre of rock above them and 2,300 metres of flooding cave passage behind them.

They were utterly alone inside the mountain, isolated from the rest of the world by the elements that were surrounding them and the rain that continued to fall outside. They might as well have been on another planet.

Ten days later, John and I were there, following the boys path into the cave through a passage that was now largely underwater. Our way forward was made not by scrambling and scurrying, but by finning and feeling. I reached out ahead of me, using my fingers to guide me. I was prepared at any moment to feel my hand collide with something soft and fleshy: a floating corpse that would have decayed rapidly after being submerged in warm water for more than a week. The discovery wouldnt be pleasant.

But that is why youre here, I reminded myself.

The water was so thick with silt that I could barely see my hand in front of my face. I had high-powered lights attached to my helmet, but they were ineffective in this murk. I only had one turned on, and that was at its lowest setting; it produced a dim glow in the brown water, which I found comforting. I listened to the reassuring mechanical sounds of my breath moving through the regulator between my lips. I breathed in air that had a familiar metallic tang. As I exhaled, bubbles escaped through my regulator and were released into the water, where they rose up until they broke and dispersed against the ceiling above our heads. When diving in a cave especially a cave with poor visibility you learn to rely on your senses in different ways than you do above ground. This was all so familiar to me.

People who are not cave divers often describe cave diving as the most dangerous sport in the world, while caves are seen by many as hostile and frightening places to be avoided at all costs. Hollywood films use caves as the setting for horrors imagined by our subconscious and appearing in our nightmares. Not all of us turn away, though. Some of us are beckoned into caves by the mystery of the unexplored. We take comfort in the very things that bring fear to others. Caves are where we belong.