Copyright 2012 National Geographic Society

All rights reserved. Reproduction of the whole or any part of the contents without written permission from the publisher is prohibited.

Published by the National Geographic Society

John M. Fahey, Jr., Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Officer

Timothy T. Kelly, President

Declan Moore, Executive Vice President; President, Publishing and Digital Media

Melina Gerosa Bellows, Executive Vice President; Chief Creative Officer, Books, Kids, and Family

Prepared by the Book Division

Hector Sierra, Senior Vice President and General Manager

Nancy Laties Feresten, Senior Vice President, Editor in Chief, Childrens Books

Jonathan Halling, Design Director, Books and Childrens Publishing

Jay Sumner, Director of Photography, Childrens Publishing

Jennifer Emmett, Editorial Director, Childrens Books

Eva Absher-Schantz, Managing Art Director, Childrens Books

Carl Mehler, Director of Maps

R. Gary Colbert, Production Director

Jennifer A. Thornton, Director of Managing Editorial

Staff for This Book

Becky Baines, Project Editor

Lisa Jewell, Illustrations Editor

Eva Absher, Art Director

Ruthie Thompson, Designer

Grace Hill, Associate Managing Editor

Joan Gossett, Production Editor

Lewis R. Bassford, Production Manager

Susan Borke, Legal and Business Affairs

Kate Olesin, Assistant Editor

Kathryn Robbins, Design Production Assistant

Hillary Moloney, Illustrations Assistant

Manufacturing and Quality Management

Christopher A. Liedel, Chief Financial Officer

Phillip L. Schlosser, Senior Vice President

Chris Brown, Vice President

George Bounelis, Vice President, Production Services

Nicole Elliott, Manager

Rachel Faulise, Manager

Robert L. Barr, Manager

The National Geographic Society is one of the worlds largest nonprofit scientific and educational organizations. Founded in 1888 to increase and diffuse geographic knowledge, the Society works to inspire people to care about the planet. National Geographic reflects the world through its magazines, television programs, films, music and radio, books, DVDs, maps, exhibitions, live events, school publishing programs, interactive media and merchandise. National Geographic magazine, the Societys official journal, published in English and 33 local-language editions, is read by more than 38 million people each month. The National Geographic Channel reaches 320 million households in 34 languages in 166 countries. National Geographic Digital Media receives more than 15 million visitors a month. National Geographic has funded more than 9,400 scientific research, conservation and exploration projects and supports an education program promoting geography literacy. For more information, visit nationalgeographic.com.

For more information, please call

1-800-NGS LINE (647-5463) or

write to the following address:

National Geographic Society

1145 17th Street N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036-4688 U.S.A.

Visit us online at nationalgeographic.com/books

For librarians and teachers: ngchildrensbooks.org

More for kids from National Geographic: kids.nationalgeographic.com

For rights or permissions inquiries, please contact National Geographic Books Subsidiary Rights:

eISBN: 978-1-4263-1033-1

v3.1

CONTENTS

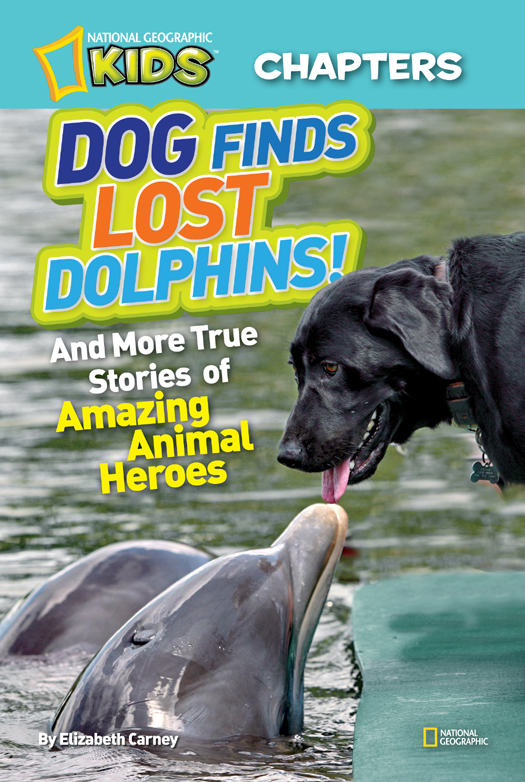

CLOUD:DOLPHINRESCUE DOG

Scientists do not always know why dolphins and whales get stranded.

Chapter 1

CALLFOR HELP

When Chris Blankenship got an emergency call to report to the beach, he expected it to be busy. And it was!

About 80 dolphins were wriggling and squeaking in the shallow water. A small army of people worked quickly to help them. Team leaders barked orders. Volunteers put on wet suits for their turn in the water. News reporters were there too. They were looking for a big story.

Chris is a dolphin expert. He has seen dolphins and whales stuck on shore before. This time was different. Usually one or two dolphins get stuck in shallow water. Sometimes they get stuck in the twisty roots of mangrove trees. But 80 dolphins! Chris thought. With so many, how do we know that weve found them all?

Every time a dolphin or whale gets stranded, it is a race against time. The sooner the dolphins are found, the easier it can be to save them. Chris ran his hands over a dolphins smooth, rubbery skin. He thought how odd it was that such a good swimmer needed help.

Dolphins are perfect for the underwater world. With their strong bodies and sleek fins, they can swim seven times faster than humans. They can hold their breath for more than 15 minutes and dive 2,000 feet (610 m) underwater.

Dolphins are also very smart. They hunt in groups. They make up games to play. They even name themselves using whistling sounds. Many researchers spend their lives learning how dolphins communicate. In a dolphins world, every click, whistle, and gesture has a meaning.

Yet sometimes dolphins end up in trouble. They can get stuck on a beach. Its a dangerous situation for them. By the time they are found, most stranded dolphins are sick or have died already.

Why would such smart animals swim so close to a beach?

We dont really know. Maybe some stranded dolphins have been sick. Maybe pollution in the water confused them. Maybe they got lost during a storm at sea.

In order to find the answer, scientists study stranded dolphins as they try to help them. They look for clues that will help them keep dolphins safe.

Chris and the animal doctors got to work on the stranded dolphins. The first step: Make sure the dolphin can breathe. Dolphins are mammals, like humans. They have lungs and need to breathe air. They take in air through a blowhole on their back, behind their head.

The stranded dolphins were very tired. They couldnt stay up on their bellies or swim on their own. People took turns holding the animals up so they could breathe. They rested the dolphins on their knees to keep their blowholes above water.

The volunteers also kept the dolphins skin moist by splashing water on their bodies. A dolphins exposed skin can dry out quickly in the hot Florida sun.