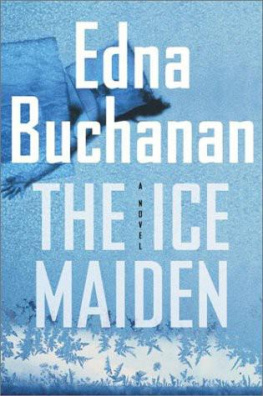

EDNA

BUCHANAN

For Teresa Johnson,

who tamed the Dragon

Some say the world will end in fire, Some say in ice.

--robert frost

1

The shoes startled me. They dangled in midair, at eye level. They were scuffed, meant for running, and they were occupied by a dead stranger who was stuck in the ceiling.

The cops were furious at the stranger.

The firefighters were irritated.

He had left them a problem: his corpse and how to extricate it. Homicide detectives, a fire department bat-talion chief with the personality of a pit bull, and an assistant Miami-Dade County medical examiner noisily debated how to tackle the job.

The dead man had missed a spectacular dawn. The rising sun had ignited a magnificent city of fire, its own face reflected in glass-and steel-walled skyscrapers.

Their flaming towers pierced a radiant blue sky, their golden glow an empty promise to shell-shocked com-muters still haunted by smoldering images of carnage and death.

The fire chief insisted that the corpse, tightly wedged in an air-conditioning grate, be pried free and lowered to the floor. Far more efficient, he claimed, than dragging dead weight up to the roof and then down a ladder. Three of his bravest, he pointed out, were still recovering from injuries suffered when they removed an eight-hundred-pound heart patient from his tiny apartment and down three flights of stairs. He wanted his men to tug the dead man's legs from below as others exerted pressure from above.

A sweaty homicide detective disagreed. The corpse was caught at the thighs. His hips were wider and his pockets stuffed with bulky items. He would have to leave the way he arrived, through the roof of this small shop, similar to so many others along Miami's downtown fringe.

"How did it happen?" I asked a young uniformed cop. "Was there exposed wiring?"

"It's absolutely shocking," he said, grinning at his little joke.

Hector Gomez, a small man in a well-pressed but shabby suit, did not smile. The proprietor of Gomez Jewelry and Watch Repair stood stricken amid plastic and cardboard displays of cheap watches and costume jewelry, his dark eyes soulfully regarding the skinny, dangling denim-clad legs.

"He was like this when I unlocked the store this morning. I think it's the same one as last time," he confided, misery on his face, voice barely audible. "I recognize the sneakers. It was raining that night. He left footprints when he climbed over the counter." We studied the soles of the well-worn Nikes. There was a distinctive pattern visible in the tread.

"The seventh breakin in two months," he whispered. "With times so hard, nobody is buying now.

How do I make a living? How do I feed my family?"

"Well," I said, "this one won't be back." He wasn't cheered. When I told him I was a reporter, he was pathetically eager to explain.

"First I installed an alarm; then I thought burglar bars would stop them, but they come in like cockroaches through the roof, stealing everything, even the watches here for repair. My customers want their watches back. Some threatened to sue me. I begged the city, the police, for help. I even wrote to the mayor.

Twice. Write that down," he said, actually wringing his hands. "They didn't answer. Nobody did. The cops don't come anymore. My place was burglarized so many times they stopped sending anybody. They take the report over the phone. If only they had listened, this never would have happened..."

"I'm listening now, pal," interrupted a burly curly-haired detective named Oscar Levitan. "You got my undivided attention. Okay?"

The detective also squinted at me, as though I too were a cockroach who had skittered in through the ceiling. "Britt Montero, ain't you supposed to be on the other side of that line?" A gangly, pimply-faced public-service aide had nearly finished stringing yellow crime-scene tape between light poles along the sidewalk outside.

"But..."

"Outside," Levitan repeated, his stare hard.

"Okay, okay." His attitude irritated me. This was no major murder mystery. Like everyone, burglars have bad days. Breaking and entering is risky business.

They crash through skylights and are cut by broken glass, caught by bullets, or nibbled on by Dobermans.

Some thieves are exterminated along with the termites inside tented buildings. One of a pair of burglars slipped while maneuvering a heavy safe down a dark and narrow stairwell; next morning he was found crushed beneath it at the bottom. Another thief executed a perfect swan dive from a third-floor ledge. He would have successfully eluded police if he hadn't missed the pool and kissed the pavement instead.

Death is an occupational hazard for thieves--or poetic justice, depending on your point of view.

I left the shop reluctantly.

"Did anybody advise this guy of his rights?" Levitan bawled to the uniformed officers.

"You're charging him?" I asked, as the detective steered Gomez out into the harsh and unforgiving glare of the relentlessly climbing sun. "Why? The burglar was electrocuted as he broke in, right? Exposed wires or poor electrical work is only a code violation, not a crime."

"Homicide," the detective said, snapping metal cuffs around Gomez's wrists, "was still a crime, last I heard."

"Homicide? You think it was deliberate?" Gomez's resignation, shoulders slumped as Levitan led him to a cage car, answered my question.

We spoke through the patrol car's half-open window as detectives and a crime-scene photographer scaled a ladder to the roof. Huddled in the backseat, wrists cuffed behind him, Gomez trembled as though cold, despite the scorching early-morning heat.

"Never would I hurt anybody," he swore, eyes moist. "I only wanted to shock them, to make them leave my shop alone." His voice cracked. "It was...

you know, prevencion. Not to kill."

"A booby trap," I said sadly. "You built a booby trap."

He gave a weak shrug. "Nothing fancy. Only an electrical cord connected to the metal grate where they come in through the ceiling. I plug it in, that's all. I didn't think it would hurt them. Only household current, a hundred and ten--fifteen--volts. A deterrent." He'd succeeded. This thief had been deterred--permanently.

Levitan waved me away from his suspect.

"You really aren't going to arrest him, are you?" I asked.

"Kidding me?" he demanded, his loosened tie hanging limply from his thick neck. "Only question in my mind is whether to book him for manslaughter or second degree. Look," he muttered under his breath, "I have to charge him." He said an assistant state attorney he'd consulted by phone had advised him to make the arrest.

"It's not fair," I said, aware I had abandoned my professional level of objectivity. "The man was a repeat victim, trying to earn a living and protect his property."

"Since when is burglary a capital offense? You can't use deadly force to protect property; it's against the law. You know that, Britt. What if some fireman went in there to fight a fire and got zapped, or a police officer chasing a suspect?"

I saw his point.

The corpse, wrestled unceremoniously down the ladder, was ready to be removed. Gomez was asked if he recognized him.

Levitan peeled back the sheet to expose the dead man's face. The watchmaker nodded solemnly.

"That's him," he said, his words nearly drowned out by angry shouts from a growing crowd. "Came into my shop once, tried to sell my own merchandise back to me. He just laughed when I threatened to call the police."

Nobody was laughing now. The dead man appeared to be in his late thirties. His pockets yielded pliers, a screwdriver, a small wrench, a crack pipe, a couple of joints, and seventy-five cents in small change. He was black. So was the neighborhood. Gomez was Hispanic.

Next page

![Fredrik Backman - Britt-Marie Was Here [Britt-Marie var här]](/uploads/posts/book/802028/thumbs/fredrik-backman-britt-marie-was-here-britt-marie.jpg)