All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever.

Introduction

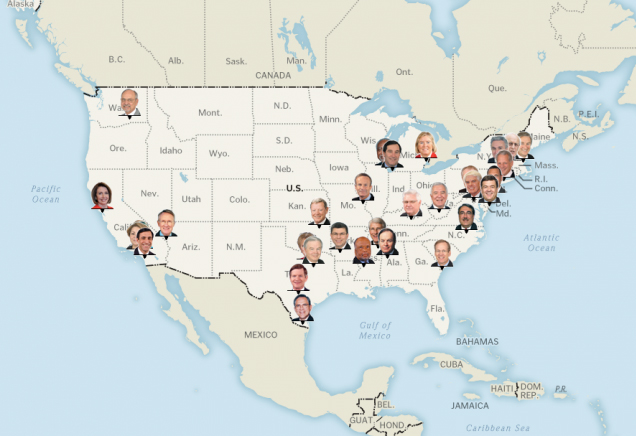

Across the nation, 33 members of Congress have helped direct more than $300 million in earmarks to dozens of public projects for work in close proximity to commercial and residential real estate owned by the lawmakers or their family members.

M embers of Congress directed millions of dollars to infrastructure projects near their residences and businesses, in some cases paving roads in front of their houses.

They made major trades in the stocks of companies pressing them for legislation.

They wrote laws favoring industries in which they were invested.

They sponsored bills on which their own family members were paid to lobby.

All of it is legal under the rules Congress has written for itself. And, the information about such potential conflicts of interest is largely obscured from the public.

In a series of stories in 2012, The Washington Post pierced the secrecy of the deeply flawed financial disclosure system of Congress. Those stories showed how 249 lawmakers have taken public actions that aligned with their private finances. Lawmakers repeatedly said the alignment was a matter of coincidence.

The Post investigation began after the nations financial crisis led Congress to unprecedented economic intervention. Reporters asked a simple question about the 535 men and women who draft the nations laws: Have lawmakers helped themselves while helping the country?

Lawmakers come to Capitol Hill from a wide range of backgrounds, including farmers, entrepreneurs, oilmen and lawyers. In office, they pursue existing family businesses and explore new ones. Members of Congress direct the nations affairs while managing their own portfolios. Some invest in real estate. Others trade in stocks.

For decades, congressional conflict of interest rules have given members broad latitude to take actions in office that not only benefit the nation, but may also benefit themselves. This freedom, they contend, is necessary so that the citizens legislature can fully represent its constituents.

Lawmakers wrote the ethics rules they have today after the Watergate scandal in the 1970s. They prohibited members from engaging in legislative activities that directly enriched themselves - and then immediately carved out exemptions to the rule. The greatest latitude was provided to lawmakers whose business interests aligned with their home-state industries.

Congress narrowly defined what would be prohibited as a conflict of interest. Lawmakers are only barred from taking actions in which they are the lone, direct beneficiaries.

The annual financial disclosure process Congress imposed on itself was supposed to provide transparency to voters. Instead it has served mainly to obscure finances while providing the appearance of transparency.

Members of Congress do not have to report the salaries of spouses, the jobs of parents or children, or the location and value of their personal residences. They can report assets and liabilities in broad ranges instead of specific amounts. No one verifies that their disclosures are completed correctly. In the digital age, the records are still maintained in a paper format and not electronically searchable.

In addition, lawmakers are not required to publicly acknowledge when they take an action that may benefit themselves or their families. They do not, for example, have to disclose if relatives have been paid to lobby for bills they have sponsored.

The extent of lawmakers private business dealings took on greater significance after the 2008 financial meltdown. The business of Capitol Hill and Wall Street converged in the bailout of auto companies and the creation of the stimulus package. Lawmakers met behind closed doors with the nations financial leaders in an effort to save the economy.

During the Great Recession, the wealthiest one-third of lawmakers were largely untouched, The Post found. Their investments took the fewest hits and quickly recovered to new heights.

The built-in congressional watchdogs the House and Senate ethics committees have been reluctant to discipline their own over lapses. Since 2004, they have moved to censure or reprimand just two lawmakers for improper use of office.

Instead, the panels issue letters that generally give lawmakers support and justification to take actions that intersect with their financial holdings. Some critics have called the panels protection committees.

Overall, The Posts coverage found that an ethical double standard existed on Capitol Hill.

The executive branch has far stricter ethics standards than Congress does and Congress has set these standards, as Craig Holman of Public Citizen, a nonprofit government watchdog group, told The Post reporters. The executive branch cant steer contracts or work to businesses where family members work. They cant even own stock in industries that they oversee, unlike Congress. Its complete hypocrisy.

To investigate how Congress public actions intersected with their private interests, The Post identified and inventoried assets held by lawmakers and their family members.

A team of reporters filled in the gaps in their financial disclosure forms, reaching into courthouses and other government offices across the nation to gather public records. The reporters examined property assessments, civil and criminal court filings, bankruptcy cases, liens and judgments.

The Post then vetted lawmakers actions in office: Where did they direct funding? Who did they advocate for? Which bills had they pushed or sponsored?

Patterns soon emerged.

In February 2012, The Post reported that 33 members of Congress had directed more than $300 million in earmarks to public projects within two miles of the lawmakers property.

In Alabama, Sen. Richard Shelby engineered more than $100 million in federal earmarks to make over downtown Tuscaloosa near his own commercial office building. In Georgia, Rep. Jack Kingston secured $6.3 million to replenish the beach where he owns a vacation cottage. And, in Mississippi, Rep. Bennie Thompson secured $900,000 that was used to resurface roads in Hinds County, including one residential loop where he and his daughter own homes.

Another 16 lawmakers steered millions to corporations, colleges and nonprofit groups connected to their immediate family. This included funding for programs run by their children and colleges where their family members work or serve on boards of trustees.

Sen. Timothy Johnson of South Dakota, for example, directed $4 million to a Pentagon program that his wife supervised as a contract employee.