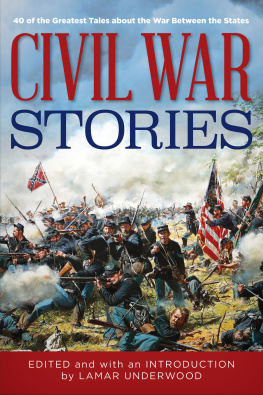

The enduring fascination of the Civil War to not only our readers but our writers was never so clear as at the first meeting we held at The Washington Post to prepare for the 150th anniversary of the war.

Every seat at the table was taken, and reporters, editors and graphic artists spilled out the door, straining to hear. Story ideas poured in. A handful of staffers turned out to be experts, able to reel off battle dates and casualty figures, and to analyze troop movements with the authority of war historians.

One wrote an homage to his state of West Virginia, which deserted its mother state of Virginia in opposition to secession. Another tracked down an ancestor who had lost a leg at Gettysburg, and didnt much like what he found. Others dug in to detail famous battles or uncover fascinating bits of trivia. We all learned about the hundreds of women who fought in the war disguised as men; the great-great-great-grandson of Frederick Douglass who, late in life, picked up his ancestors cause to fight modern-day slavery; and the evolving philosophy of how to best preserve Civil War battlefields.

We are delighted to bring our Civil War sesquicentennial coverage to a larger public with this ebook.

Painful lessons the Civil War taught us

By Philip Kennicott

Twice before, the United States has celebrated major anniversaries of the Civil War, and twice before, a nervous sense of reticence governed the events. Fifty years after the guns fell silent at Appomattox, there were still living Civil War veterans, racial antagonism was virulent throughout the country, and segregation was both pervasive and institutionalized. Fifty years later, when the nation commemorated the centennial of the war, communism loomed as an outside threat, while many believed that the civil rights era was creating instability from within. In both cases, official policy was to stress reconciliation rather than reopening old wounds.

Now we have come to the 150th anniversary, and the habits of treading lightly on the old divisions that caused the Civil War are thoroughly engrained. Interest in the war remains vital the Library of Congress estimates that it has about 26,000 volumes about the war, twice as many as about the Revolutionary War. In a nation that frets about historical illiteracy, we congratulate ourselves on our passion for the Civil War, even as politicians and self-appointed cultural defenders regularly obfuscate its causes and allow essential chapters to be distorted or discarded from the annals.

As the 1968 Civil War Centennial Commission report to Congress described the state of American history before the last big anniversary, The social, cultural and economic history of the war era were neglected in favor of drum, bugle, and cannon smoke. We are not much better off today.

And so some of the most powerful lessons of the war years, and the events leading to the election of Abraham Lincoln, remain elusive. The Civil War taught us, as a nation, our patterns of argument, our impatience with hypocrisy, our sense that every election is an apocalypse. It taught us how to be stupid, how to provoke our enemies, how to resist modernity, how to fight on after logic and argument have failed. Even the central idea upon which Lincoln ran for office, and which governed his decisions over the course of his presidency, is still painful for many people to accept.

Lincoln, who was elected the 16th president of the United States on Nov. 6, 1860, came to office believing history was on his side.

Two Americas

Shortly after he was elected president, Lincoln had a vision: He looked in the mirror and saw his face twice, one image reflecting the full glow of health and hopeful life and the other showing a ghostly paleness. According to his friend Ward Lamon, Lincoln believed this was a premonition of the future, that he would die during a second term in office.

There is a simpler and less superstitious reading. For years, Lincoln and his Republican allies had argued that there were two Americas a house divided in the young republic: a vital, strong and growing North, and an enervated South, doomed by slavery to failure. Republicans were more than capable of what Southerners decried as arrogance and insolence in their sociology of the South. But the Republican view was based on ineluctable fact: The North had more and better railroads, canals and schools; its economy was more diverse; its population was growing. Some strata of Southern society flourished when cotton prices were high the average white male was richer in the South than the North but by almost every social and economic metric, the South was behind and falling more so.

But Lincolns view of two Americas was also based on an idea which we might call History, with a capital H. This was a 19th-century understanding of history, which included and transcended religion, economics, politics and morality. The idea of History as an upward spiral of progress is out of fashion today. But for Lincoln, it was everywhere, including in the books in his Springfield, Ill., law office, and on the north pediment of the U.S. Capitol, where a sculpture finished in 1863 shows America embodied as a woman in flowing robes, flanked by figures of progress, with a sun rising at her feet.

History, with a capital H, could be read even in the smallest details of daily life. When Northerners toured the South, they saw fences in disrepair. William Seward, who would be Lincolns secretary of state, wrote in 1846 that in the South the land was sterile, the fences mean. The broken fence, like an unmowed lawn, was a visual metaphor for a broken society in which slavery was dragging an entire culture into barbarism.

Frederick Law Olmsted, who as a father of American landscape design would create refuges for the huddled, wage-earning, urban masses common in the North, visited the South and compared the two regions, asking, Why it is that here has been stagnation, and there constant, healthy progress?

His answer: It is the old, fettered, barbarian labor-system.

Fences were an ideal image to explain the Free Labor ideal of Northern Republicans. A multiplicity of fences on the landscape suggested a community of prosperous small entrepreneurs, invested in property; and a well-maintained fence demonstrated a mans commitment to self-improvement and prosperity. The broken fence proved that the laborers of the South slaves would never be emotionally invested in their work, and by extension in economic progress.

The broken fence had no place in Lincolns greatest, and perhaps most flawed, idea: that there was a nascent middle-class utopia rising in the North, a mix of small farms and industry, in which work invested citizens in community and labor wasnt just about survival but a positive process of education. He seemed to envision Thomas Jeffersons yeoman farmer educated in a land grant university. In an 1859 speech, Lincoln described what he called thorough work, which meant not just productive farming, but mental and intellectual engagement with labor. He praised the effects of thorough cultivation upon the farmers own mind, and by extension, he argued that by the best cultivation of the physical world, beneath and around us; and the intellectual and moral world within us, we shall secure an individual, social, and political prosperity and happiness, whose course shall be onward and upward.

![Fawcett - How to lose the Civil War : [military mistakes of the War between the States]](/uploads/posts/book/92687/thumbs/fawcett-how-to-lose-the-civil-war-military.jpg)