BFI Film Classics

The BFI Film Classics is a series of books that introduces, interprets and celebrates landmarks of world cinema. Each volume offers an argument for the film's 'classic' status, together with discussion of its production and reception history, its place within a genre or national cinema, an account of its technical and aesthetic importance, and in many cases, the author's personal response to the film.

For a full list of titles available in the series, please visit our website:

'Magnificently concentrated examples of flowing freeform critical poetry.'

Uncut

'A formidable body of work collectively generating some fascinating insights into the evolution of cinema.'

Times Higher Education Supplement

'The series is a landmark in film criticism.'

Quarterly Review of Film and Video

'Possibly the most bountiful book series in the history of film criticism.'

Jonathan Rosenbaum, Film Comment

Editorial Advisory Board

Geoff Andrew, British Film Institute

Edward Buscombe

William Germano, The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art

Lalitha Gopalan, University of Texas at Austin

Lee Grieveson, University College London

Nick James, Editor, Sight & Sound

Laura Mulvey, Birkbeck College, University of London

Alastair Phillips, University of Warwick

Dana Polan, New York University

B. Ruby Rich, University of California, Santa Cruz

Amy Villarejo, Cornell University

Contents

Introduction

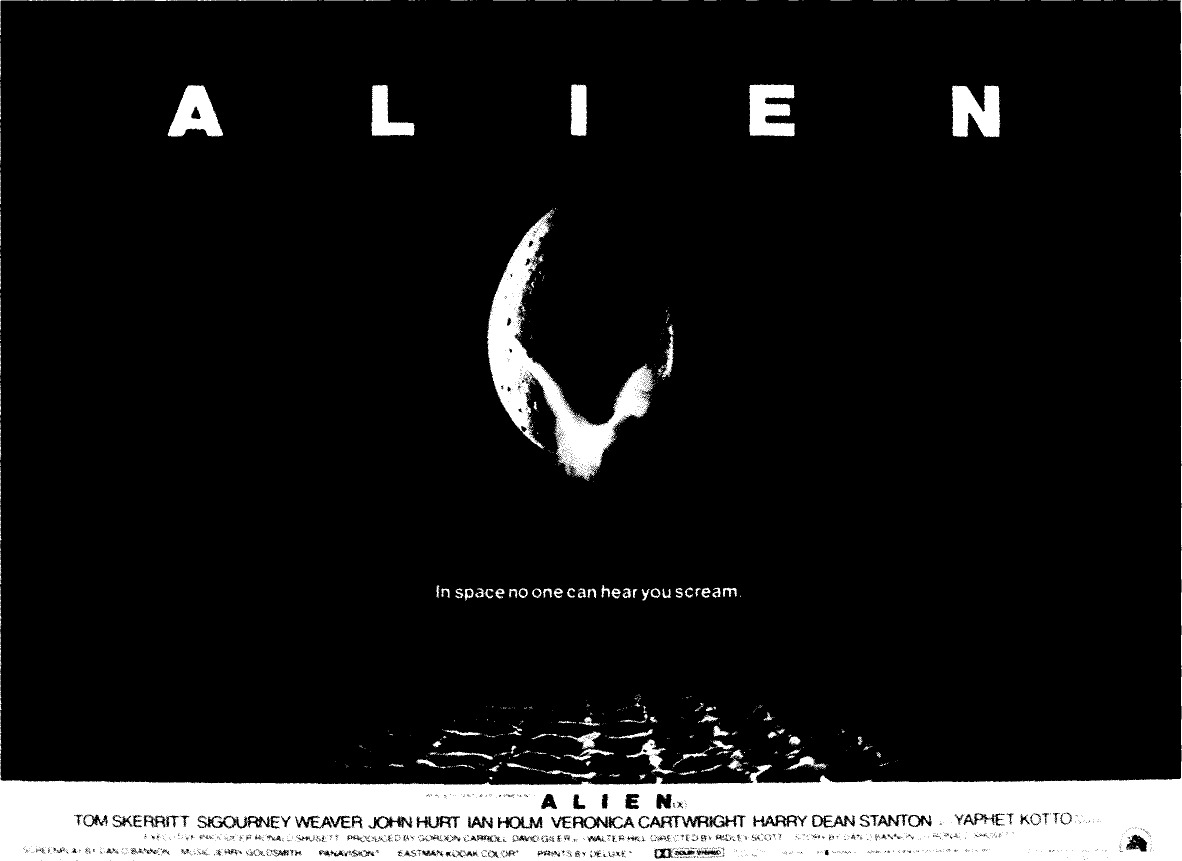

In 1977, a heavily revised script optioned by Twentieth Century-Fox entitled Alien went through the hands of several Hollywood directors. Peter Yates passed on it. Robert Aldrich passed on it. The veteran Jack Clayton, director of the brilliant ghost story The Innocents (1961), dismissed it as 'a stupid monster movie'. The Screen Directors Guild then went on strike. Eventually, the English director Ridley Scott was signed up in February 1978. Scott had a long track record in advertising but not so much experience in studio film production. He had released his first feature film, The Duellists, in 1977, which was not strongly promoted by Paramount. It had shown in precisely one cinema in Los Angeles.

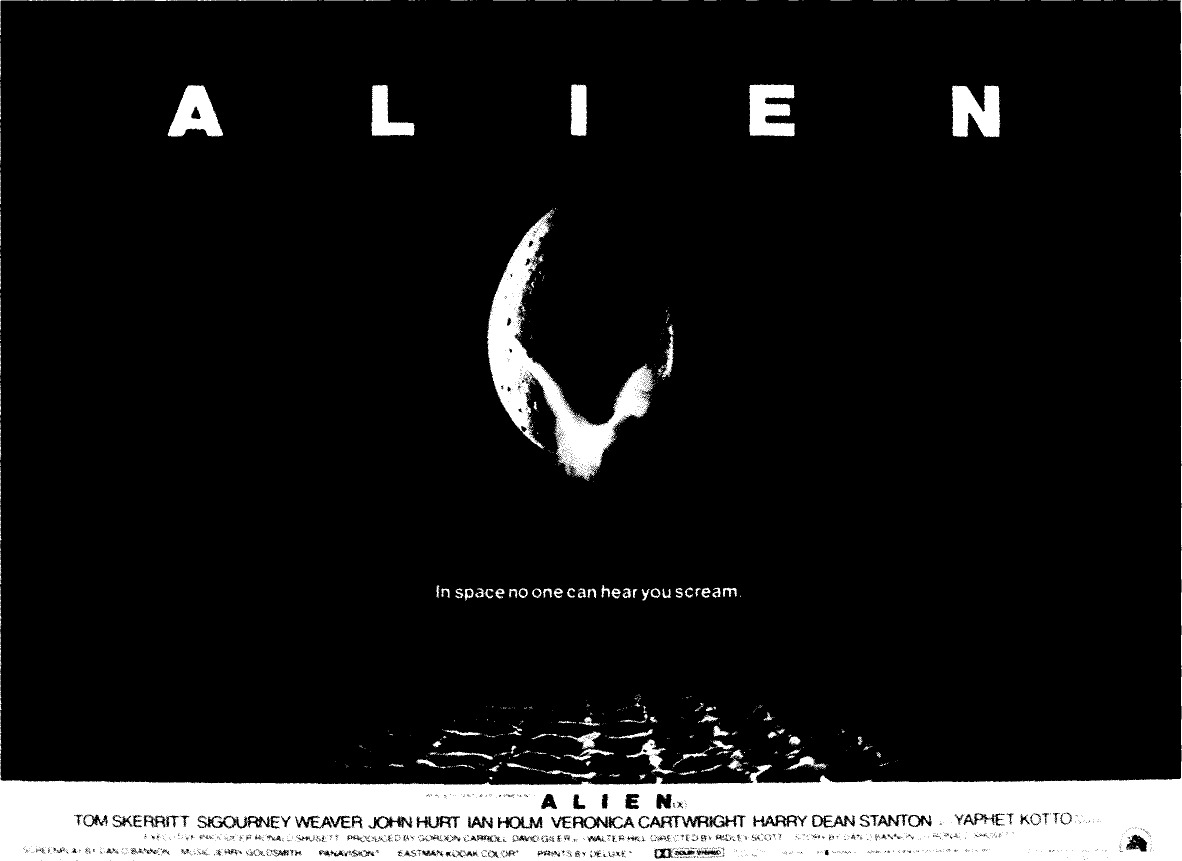

When Alien opened in May 1979, with a saturation ad campaign, it was to lukewarm reactions. In the New York Times, Vincent Canby warned that it provided 'shocks of a most mundane kind' and called it 'an extremely small, rather decent movie of its modest kind, set inside a large, extremely fancy physical production'. The Monthly Film Bulletin praised only its 'commercial astuteness', complaining at its 'moribund' narrative which 'seems to dispense with dramatic structure altogether' and mourned its general 'lack of invention'. James Monaco in Sight & Sound thought it had little intellectual content and 'has no other reason for being except to work its effects on audiences'.

This is not a promising start for what became one of the most potent myths of modern cinema. Alien did in fact do well commercially: it was the fourth largest grossing film of 1979 (earning $60 million in America). But texts give birth to myths once stories escape the bounds of their local plot and float free from their origins. Gothic fictions have done this continually across the centuries: Shelley's Frankenstein, Stevenson's Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde or Bram Stoker's Dracula have each provided powerful icons, condensing something about what it means to be human in the modern world with such incredible economy and force that they broke their literary bonds and became embedded in the general culture. Alien undoubtedly has the same force as its Gothic forebears, bursting out of its modest origins and coiling itself around our darkest imaginings.

So far, Alien has spawned three direct sequels (1986, 1992 and 1997), many revised versions and directors' cuts of each film in the series, a sort of prequel (Prometheus, 2012) and an associated franchise - Alien vs. Predator (2004) and Alien vs. Predator: Requiem (2007). More films in these series are slated for development. The 1979 Alien appeared immediately as a novel, a comic and a 'foto-book' (helpful for those, like me, who were too young to see an X-rated horror film but could pounce on the stills instead). Aliens (1986) was followed by the launch of a series of comics from Dark Horse, then a set of novelisations exploring this shared world. When video games became a significant income stream in the 1990s, the plotting of Alien proved highly conducive to the shoot-em-up gaming format and several games based on the film have appeared since. Special DVD box sets, anniversary editions and associated merchandise continue to pour out, as does a vast archive of writing by academic critics and equally learned fans. In 2011, Fox released the book Alien: Vault, another account of the making of the film, replete with exhaustive memorabilia. On the thirty-fifth anniversary there was yet another official book, Alien: Archives, a new video game, Alien: Isolation, two comic series (one each in the Alien and Prometheus world) and a brand-new set of Alien novels. Fox also announced the first Ripley collectible action figure, as well as related 'plush toys and bobbleheads'. None of this looks likely to stop any time soon.

What was it in this creaky Old Dark House in Space, this interstellar slasher, that gave it the evolutionary advantage to survive the late-1970s glut of horror hybrids? The story of how Alien came together in the form it did is a series of glorious accidents, a chance result of arguments and compromises that would surely have wrecked a hundred other films. Cinema, like myth, rarely springs from a single intent, and Alien was moulded, at every level, by the forces of something collective, beyond itself, that pushed it into a shape that nevertheless felt instantly necessary and preordained.

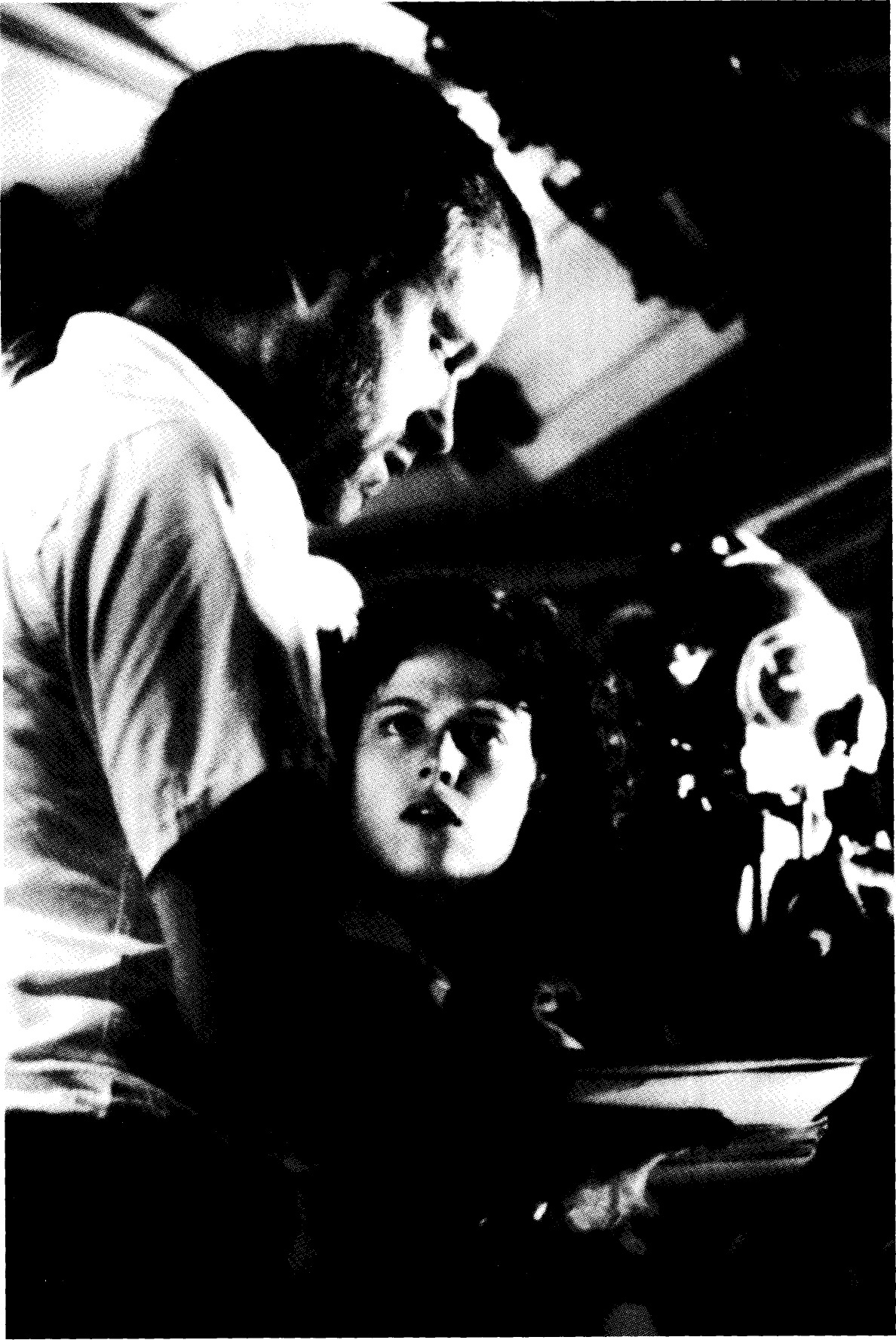

Scott and Weaver on set

This book is an attempt to account for the cultural fascination Alien has generated. For me, it is a boundary fiction, a film that rests on a number of cusps. These kinds of films do a lot of cultural work for us, negotiating limits and meanings. It is why we keep returning to them. Alien is a late-1970s studio film, given the green light by a studio keen to repeat the success of Star Wars (1977), yet it retains a late whiff of that independent spirit of the New Hollywood and even a dash of European art-house sensibility. An efficient thriller plot, honed by tough-guy director Walter Hill, was ornamented to baroque excess by the extraordinary concentration of artistic talents that came to work on the film. Low trappings came with high style.

After Alien